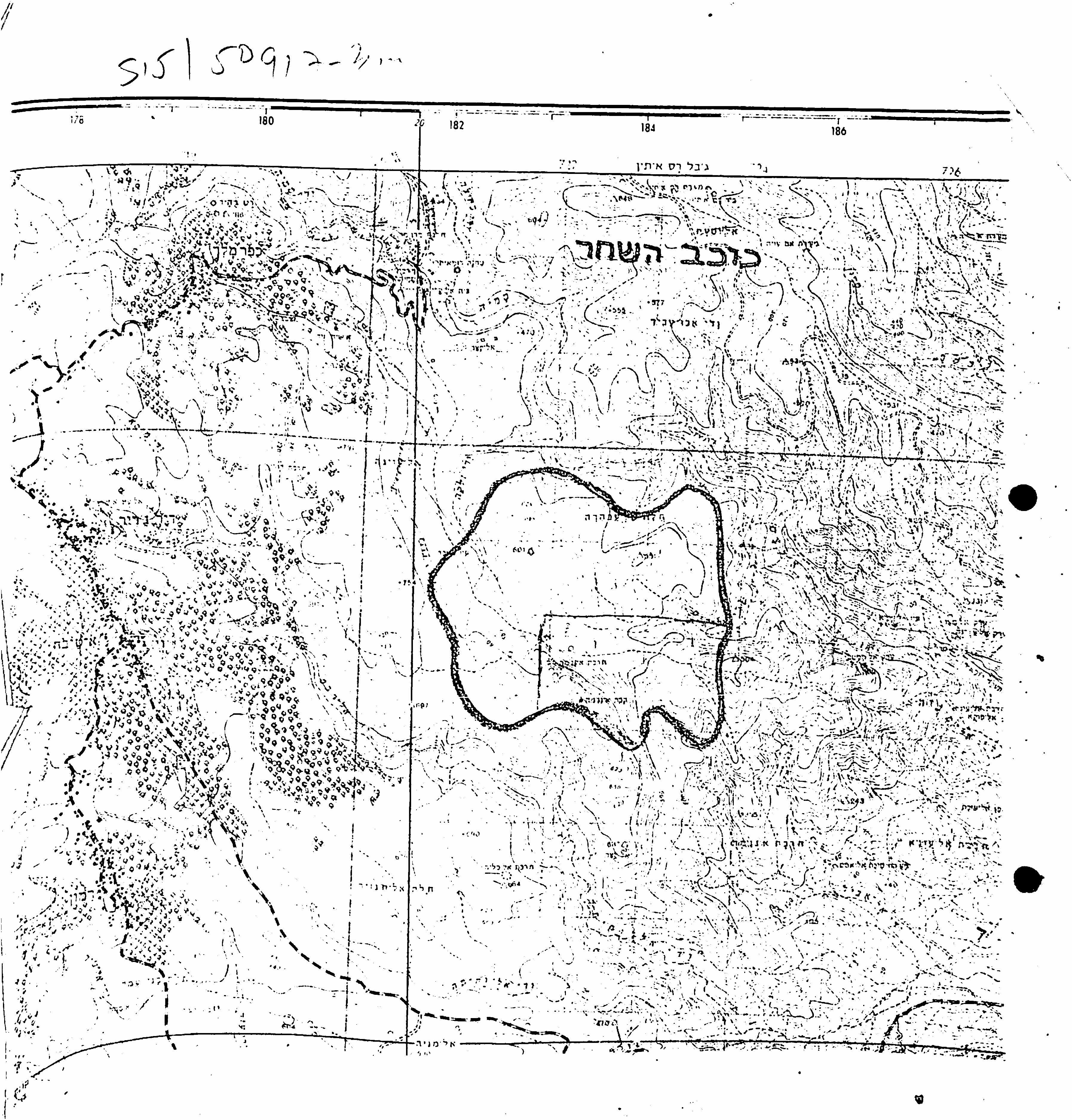

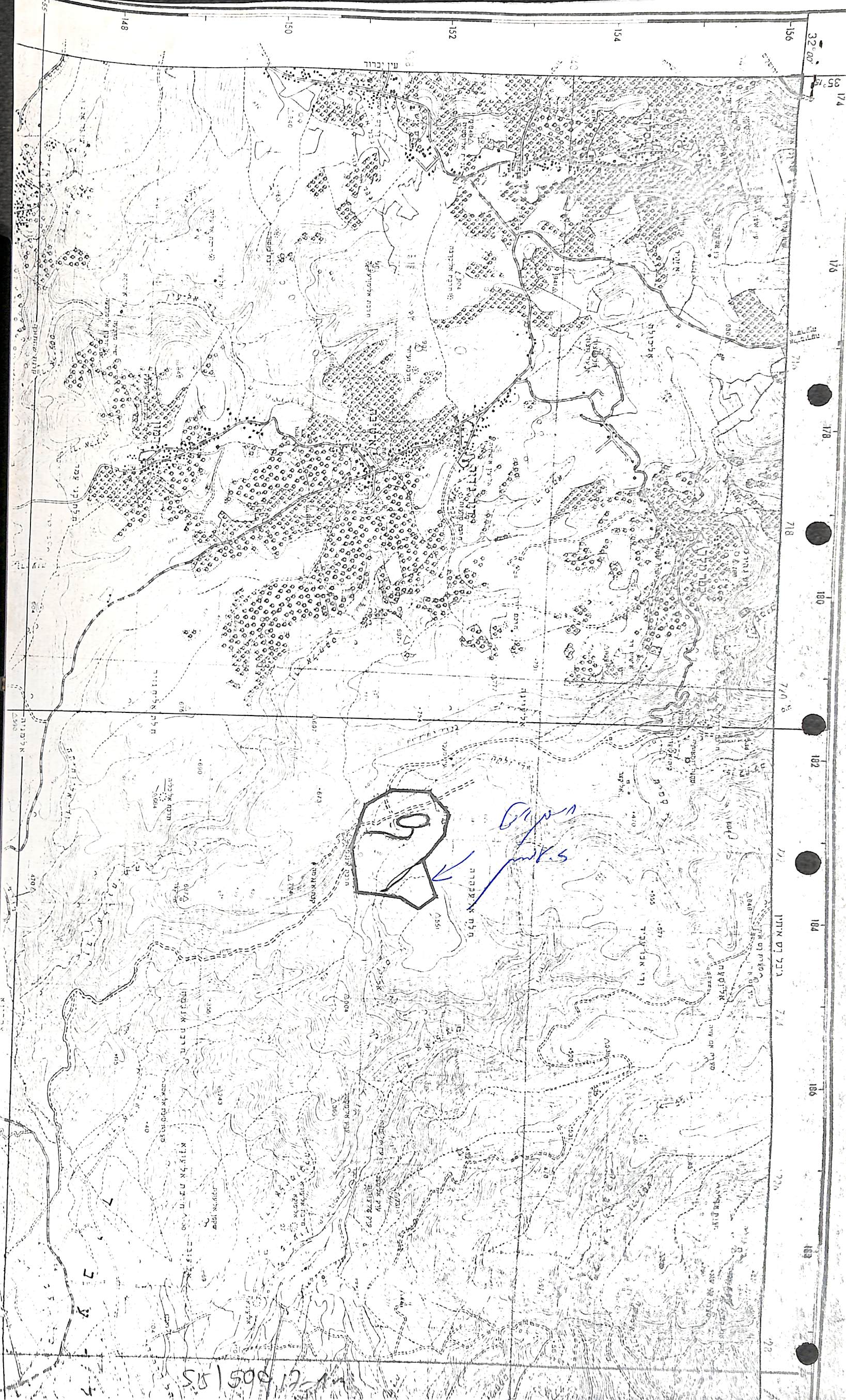

About 130 settlements have been built in the West Bank since it was occupied in 1967. Often, building these settlements required creative ways to take over land. A common method was to use a security excuse: training grounds, firing zones, seizure for military needs. In many cases, these reasons camouflaged a different purpose, more political than military. A prime example is the settlement of Kokhav Hashahar. The settlement’s website gives a very brief description of its origins: “In 1975, a Nahal military base was built at the site. It functioned until 1980 when a founding group of about ten young couples arrived and built Kokhav Hashahar.” How did Palestinian land become a military base that then became a civilian settlement?

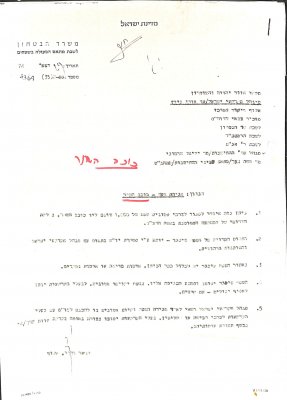

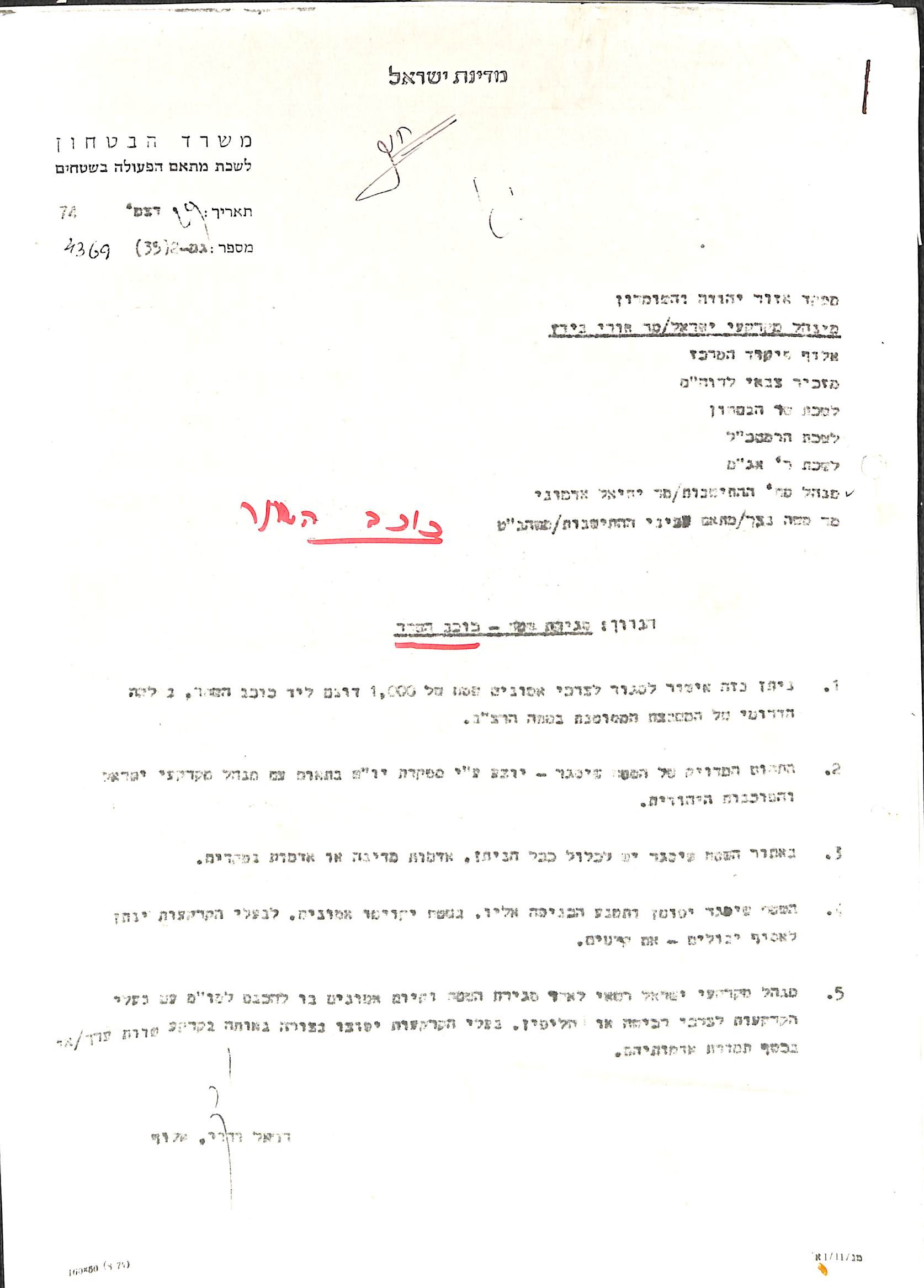

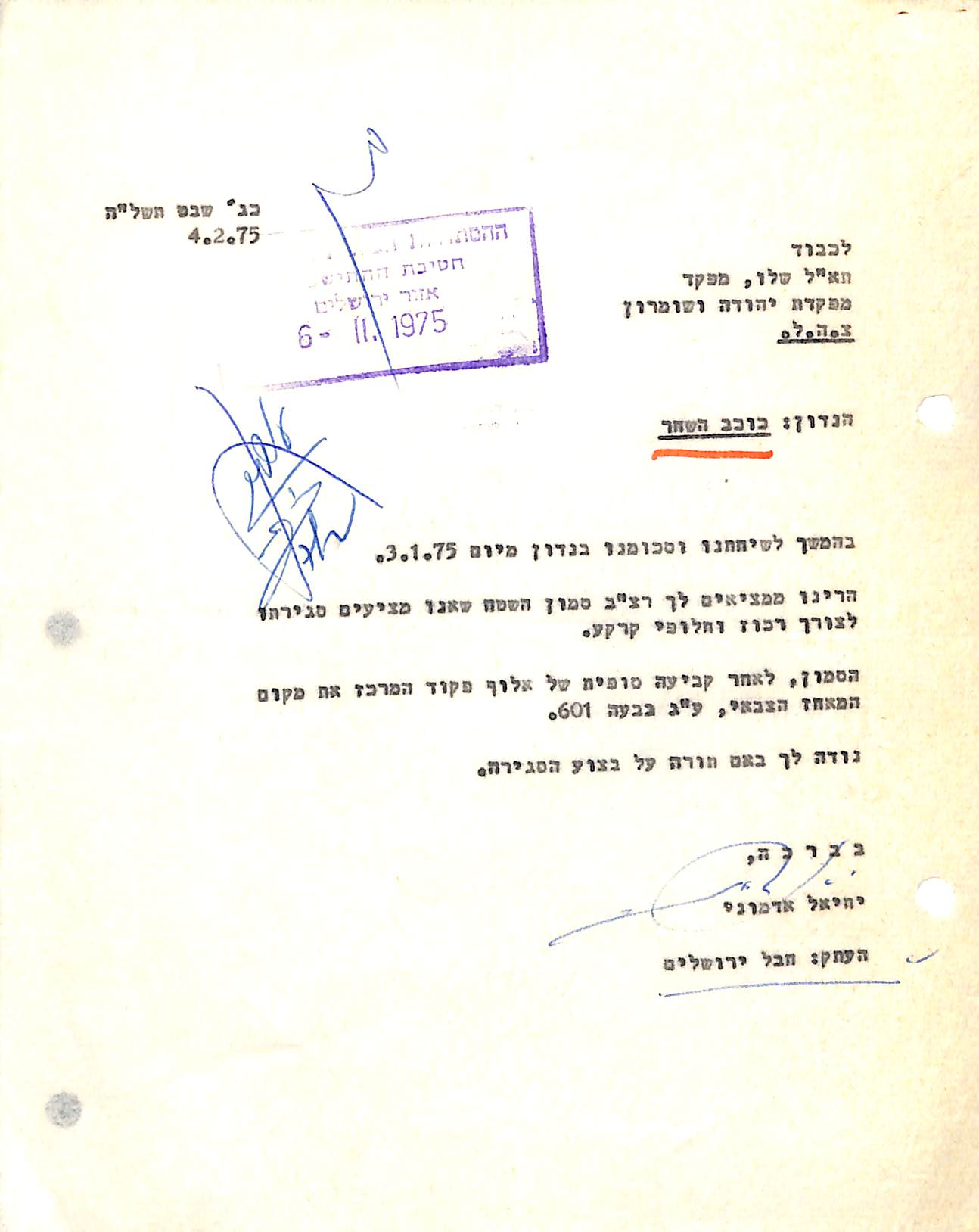

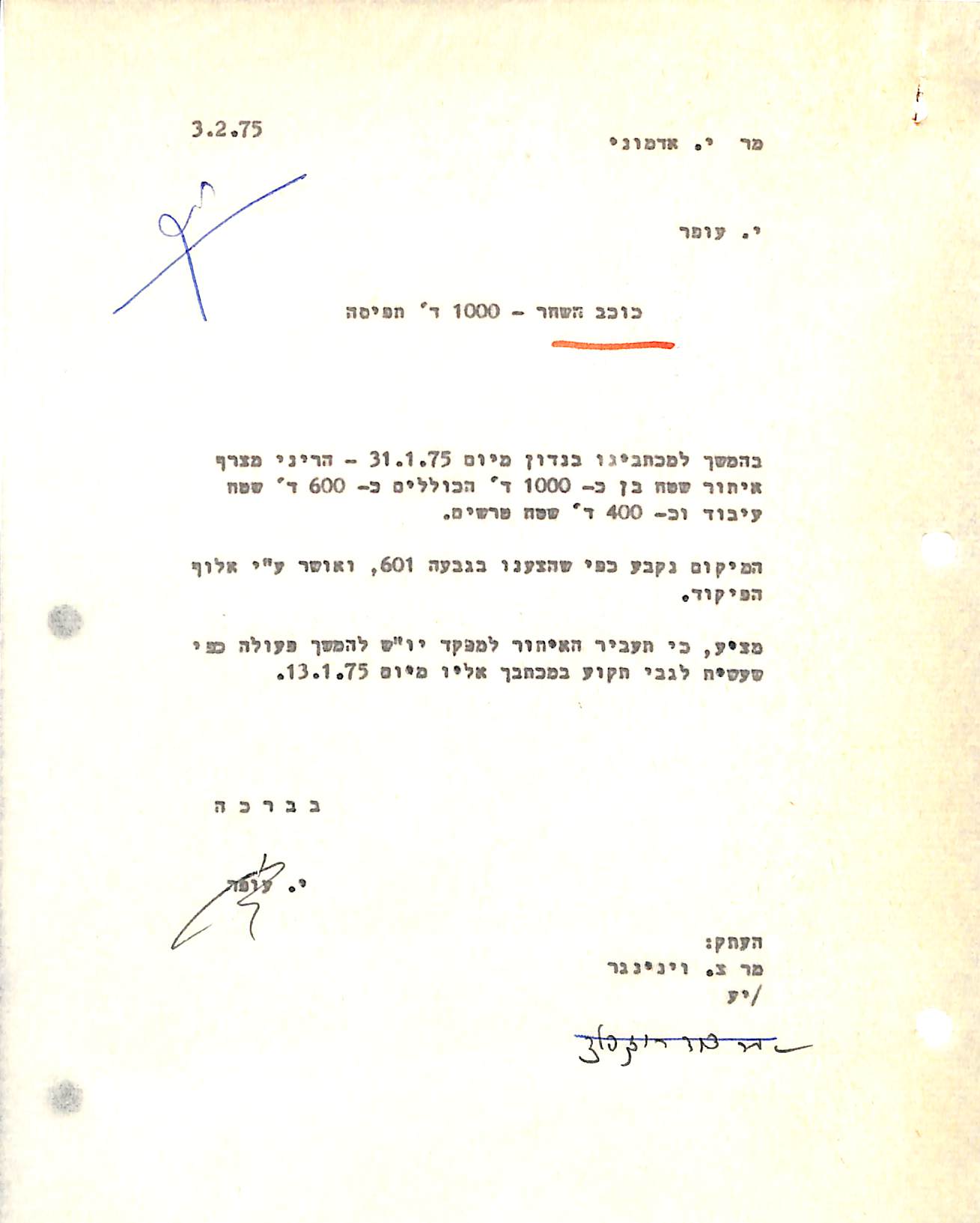

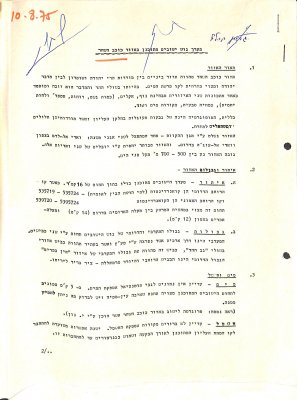

In the letter, Major General Vardi gives official approval to close 1,000 dunams for a military training ground, stating the closed area should include “to the extent possible” state land (meaning land registered as owned by the Jordanian Crown), or lands belonging to absentee Palestinians. The letter further states that the parameters of the area designated for closure would be proposed by the military in coordination with the Israel Land Administration and the Jewish Agency.

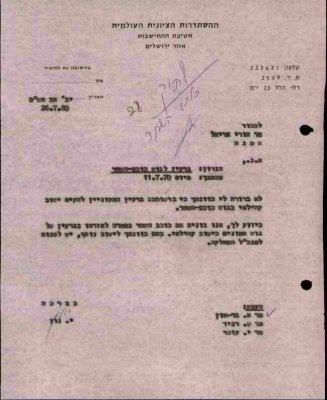

The director of the Jewish Agency’s settlement department was instrumental in the establishment of outposts and settlements in the 1970s, including Kokhav Hashahar. This document is part of correspondence relating to the identification of the specific area designated for “training.”

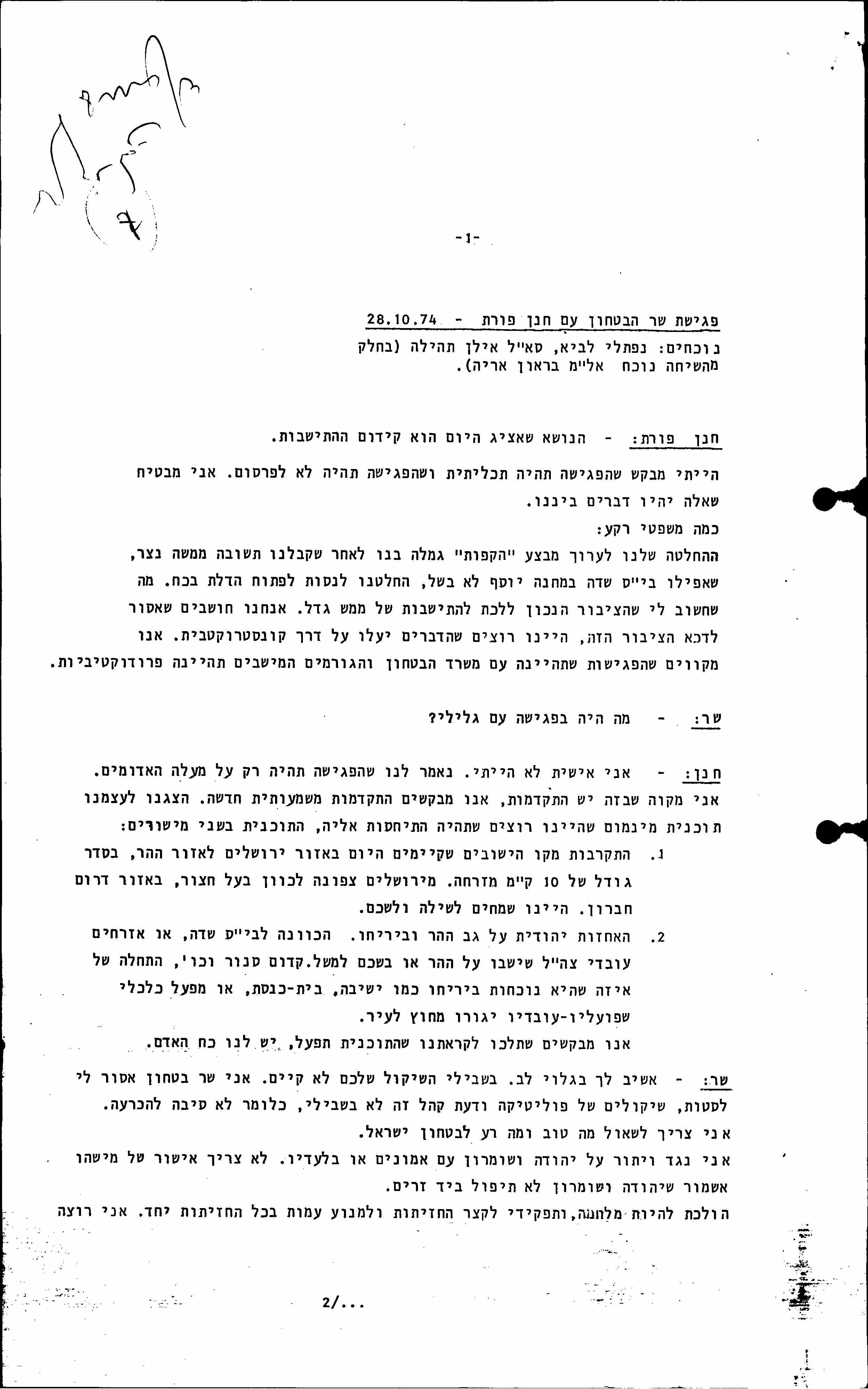

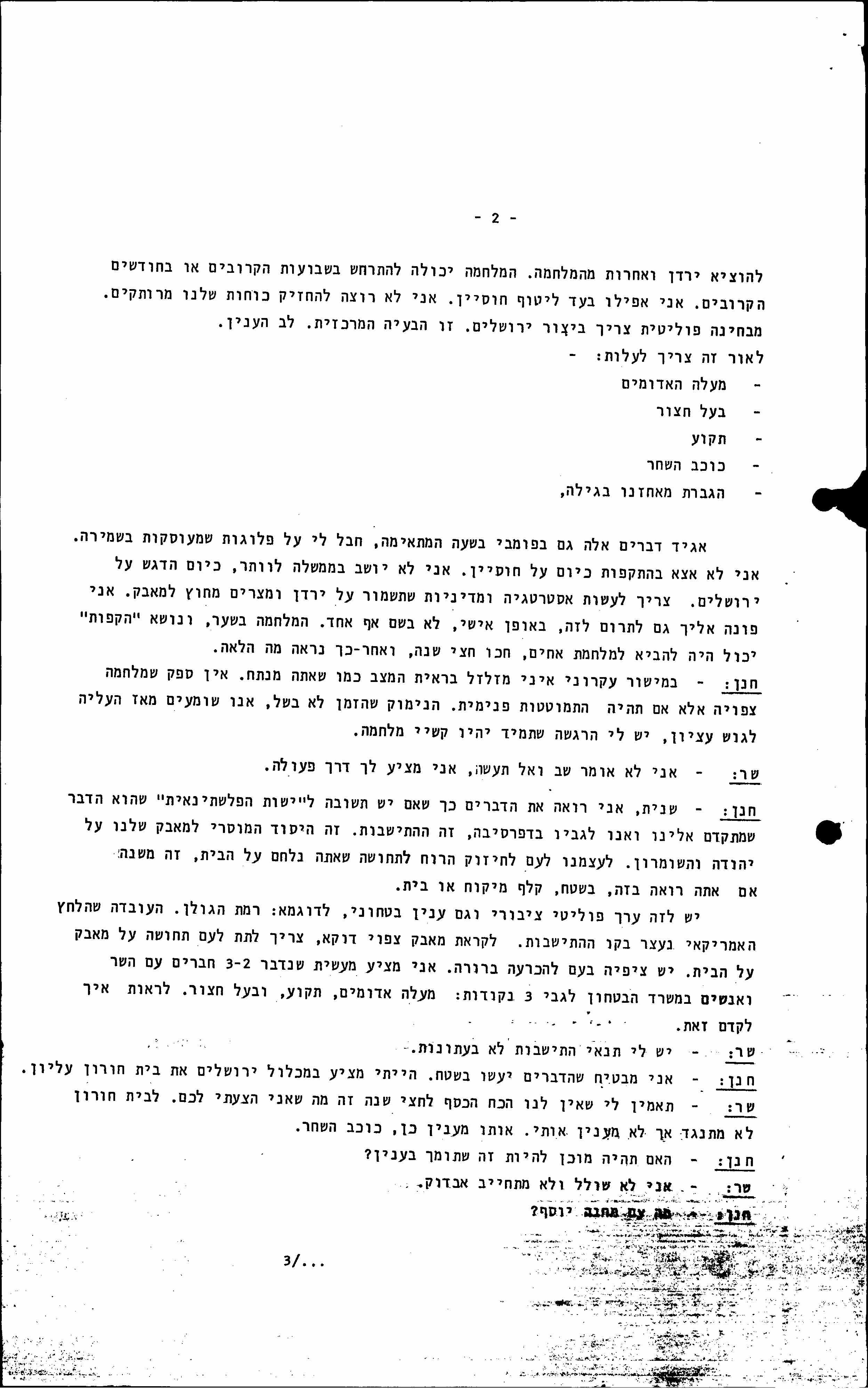

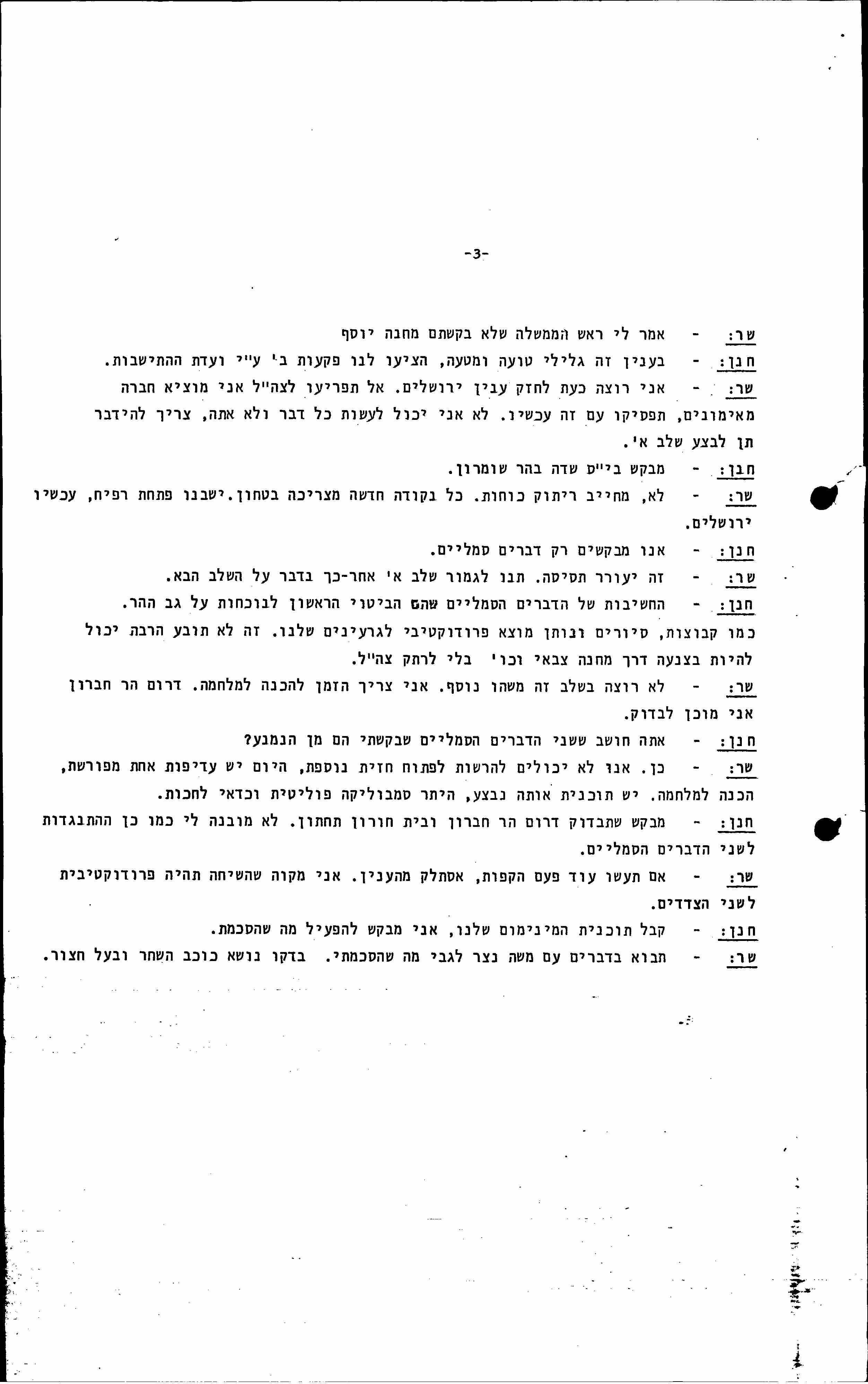

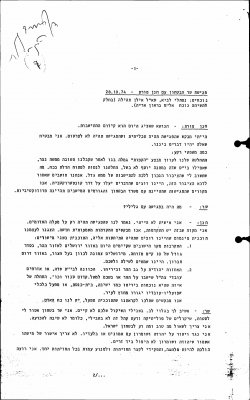

Transcripts of a meeting between Defense Minister Shimon Peres and Hanan Porat, a Gush Emunim founder, one of the first settlers in Gush Etzion and later a member of Knesset for Mafdal (a right-wing party that championed Jewish settlement in the West Bank) – focusing on the future of Jewish settlement in the West Bank. The transcripts of the conversation, which was private and not meant for publication at the time, expose the close relationship between the settlement movement and the political establishment, particularly the Ministry of Defense. In the conversation, Peres tells Porat he supports settlement in the West Bank, and states specifically that for political reasons, he approves settlement in Ma’ale Adumim, Baal Hazor, Tekoa and Kokhav Hashahar and expansion of the settlement in Gilo.

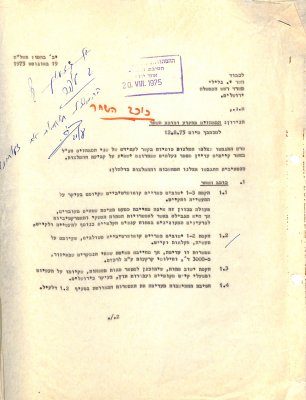

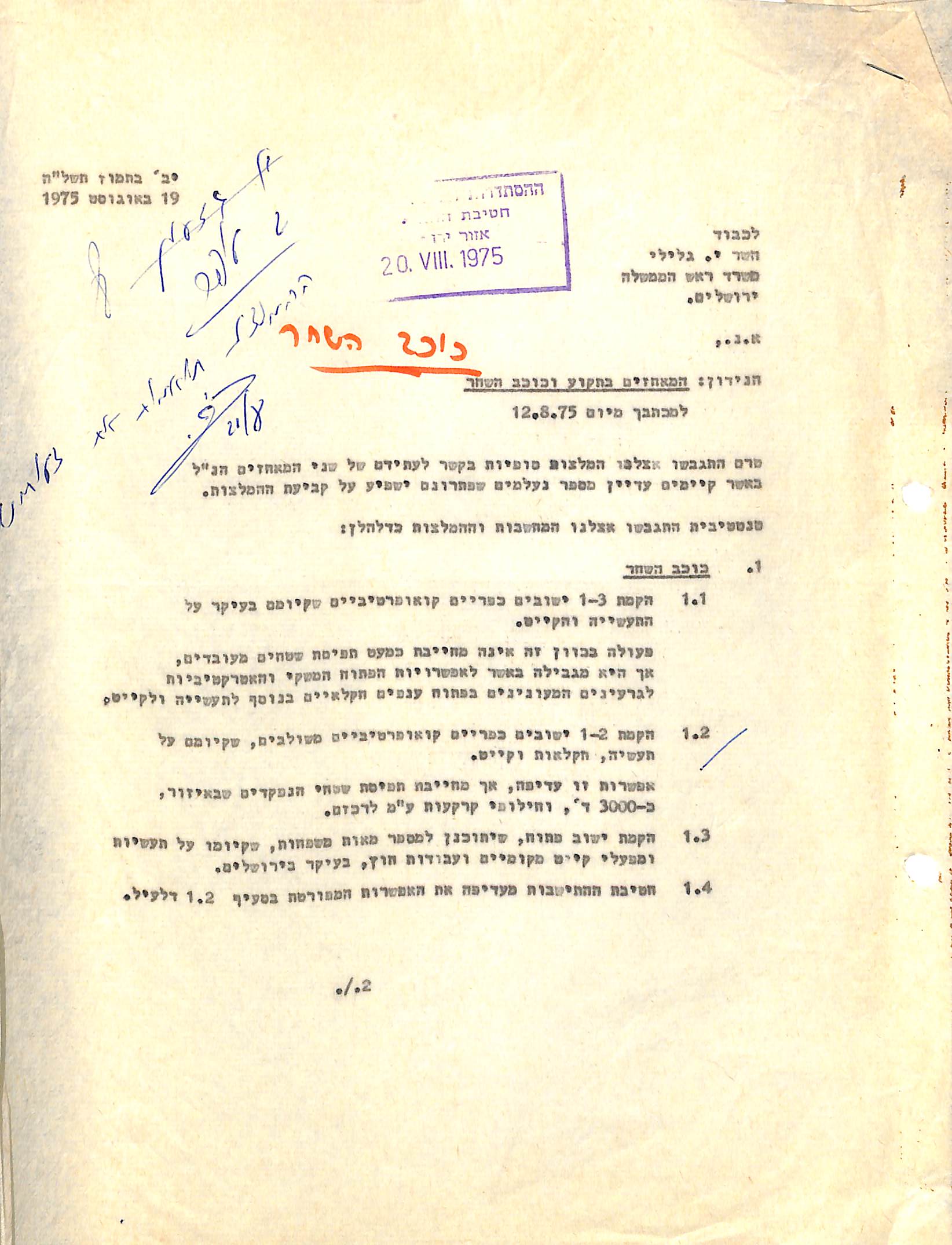

In his letter to Minister Yisrael Galili, who served as the chair of the Settlement Committee at the time, Admoni lists points and recommendations for the outposts set up in Tekoa and Kokhav Hashahar. He suggests several options for settlement in Kokhav Hashahar and notes the Jewish Agency prefers the option of 1-2 cooperative, incorporated communities that would rely on industry, farming and tourism. Admoni notes that this option would require seizing about 3,000 dunams of absentee land in the area.

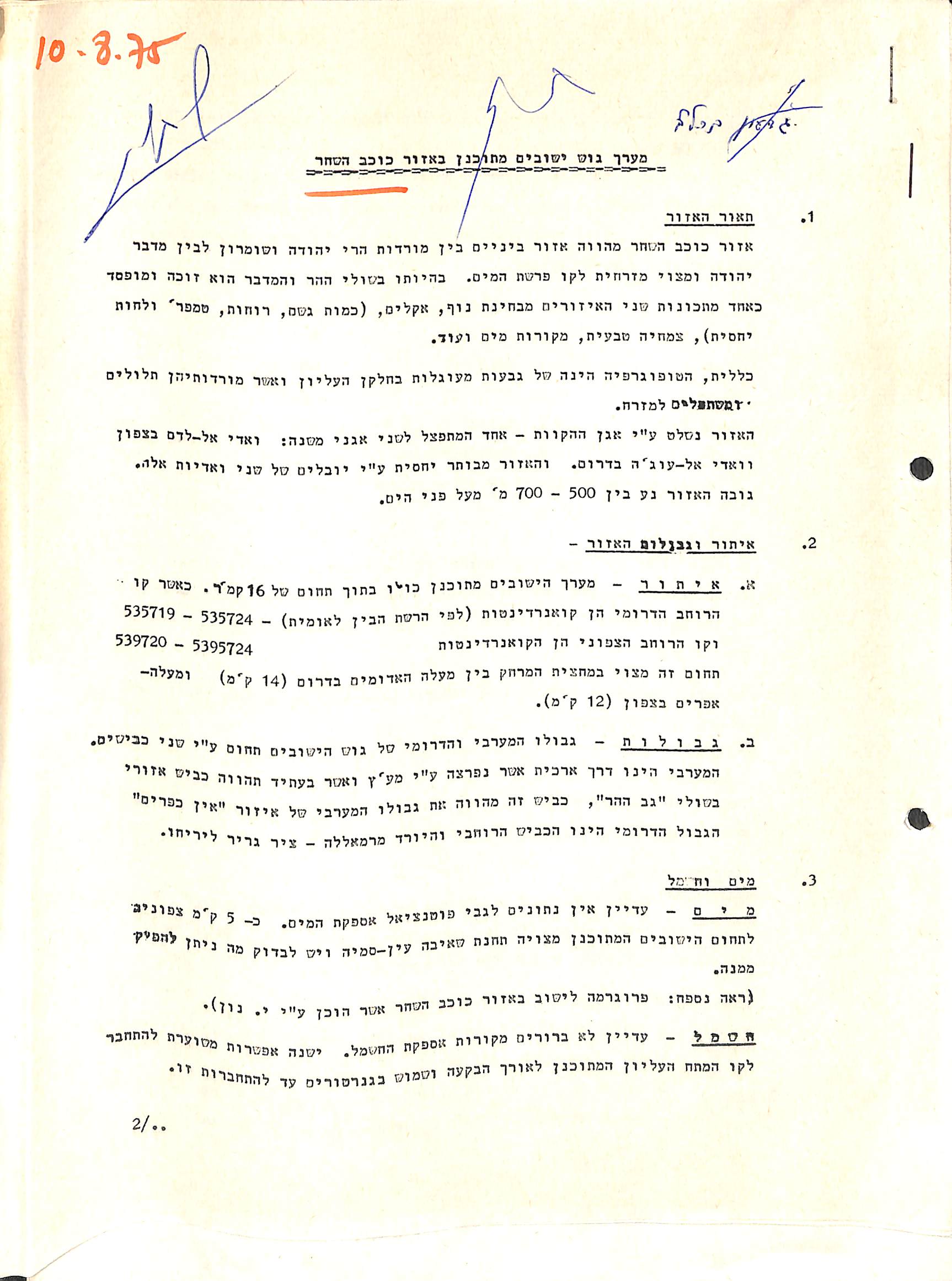

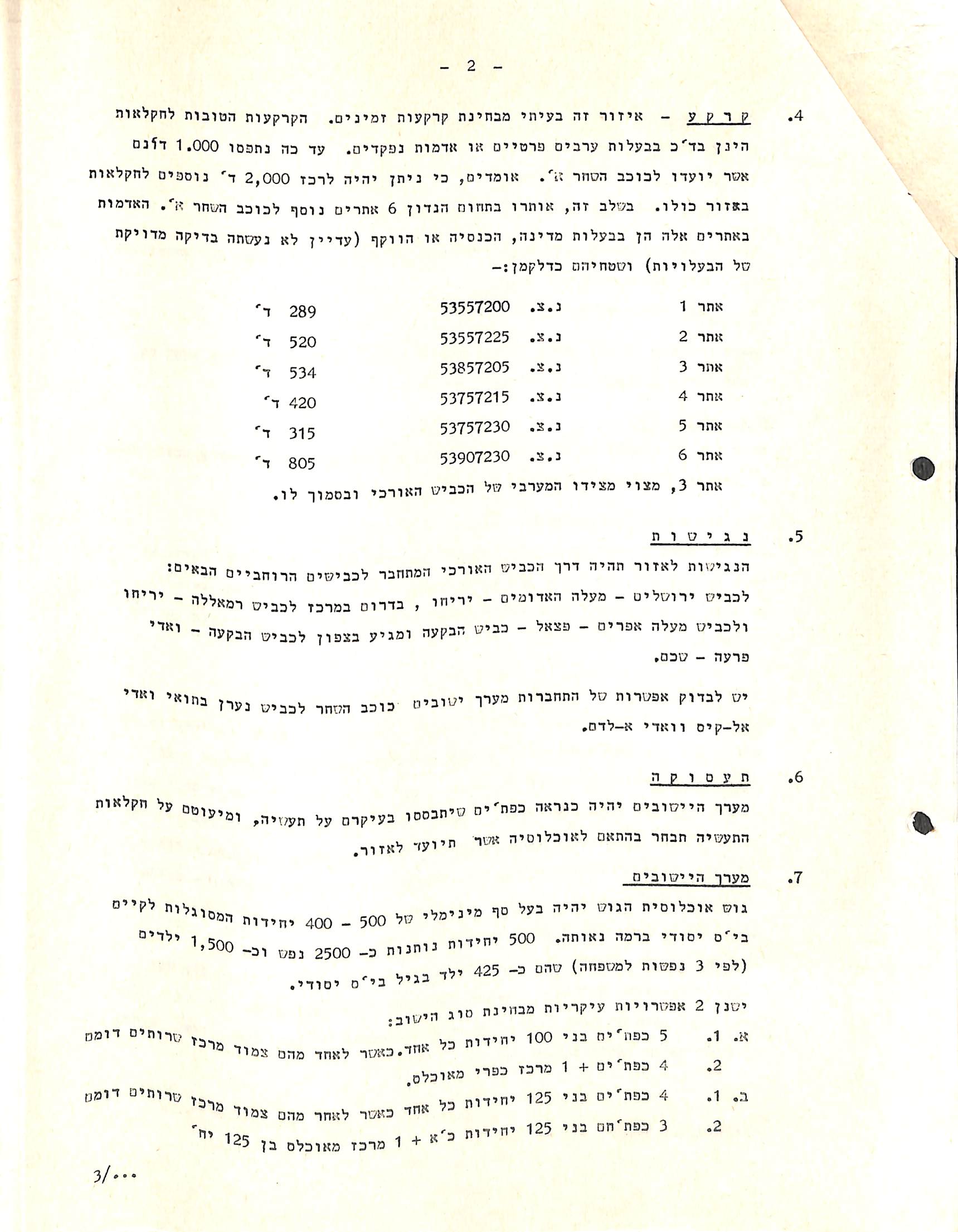

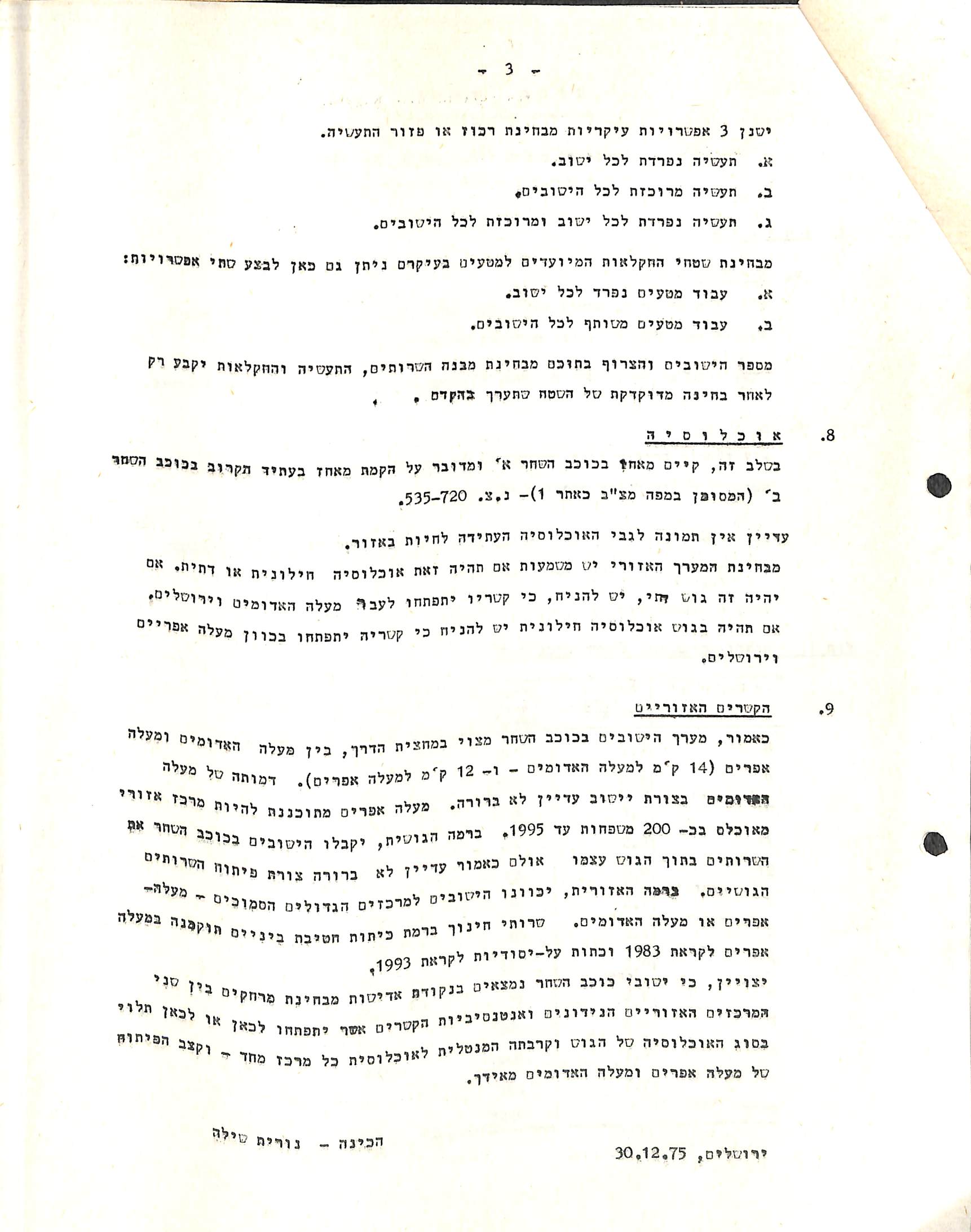

This is likely an internal document written by the Settlement Division of the World Zionist Organization, reviewing options for prospective settlement, industry, farming, demographic make up and other aspects for a settlement block in Kokhav Hashahar. The document was used in discussions about the future of an area initially closed for military training.

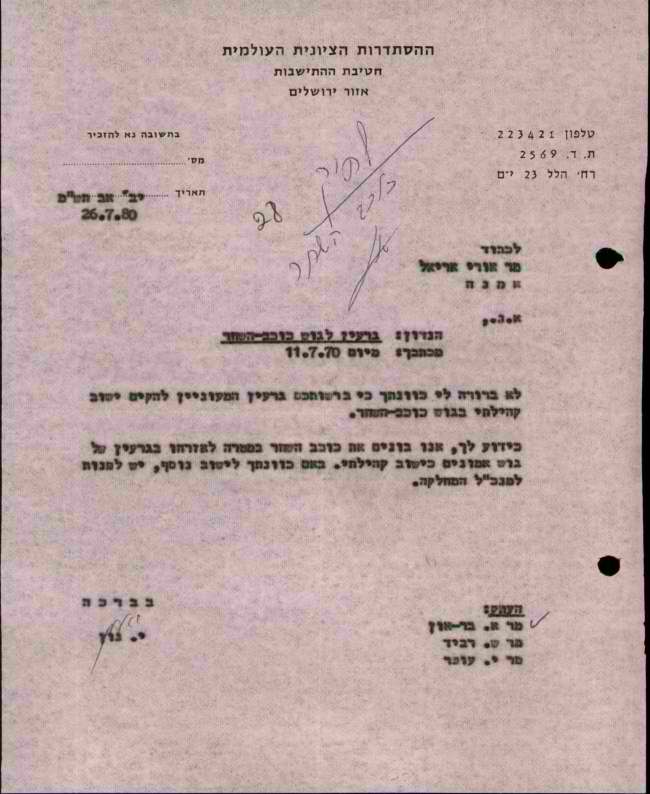

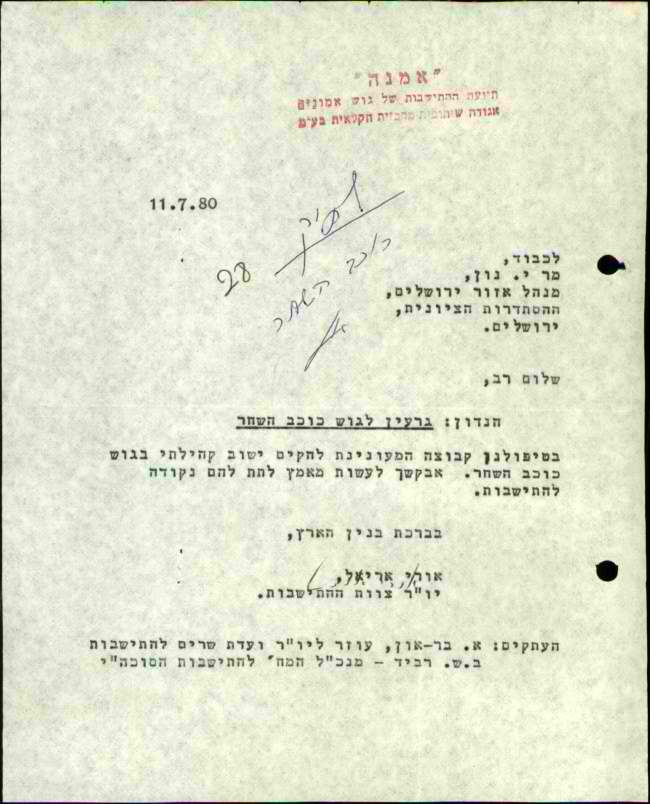

In this letter, Yeshayahu Nun replies to an inquiry from Uri Ariel regarding a group that was interested in establishing a settlement in Kokhav Hashahar. Nun clarifies in the letter that the Settlement Division was already working on turning the military outpost built several years earlier into a civilian community and settling members of Gush Emunim at the site. This was, in fact, the fulfillment of the promise Peres made to Hanan Porat in 1974, documented in the transcripts of their meeting from October 28, 1974.