About 130 settlements have been built in the West Bank since it was occupied in 1967. Often, building these settlements required creative ways to take over land. A common method was to use a security excuse: training grounds, firing zones, seizure for military needs. In many cases, these reasons camouflaged a different purpose, more political than military. A prime example is the settlement of Kokhav Hashahar. The settlement’s website gives a very brief description of its origins: “In 1975, a Nahal military base was built at the site. It functioned until 1980 when a founding group of about ten young couples arrived and built Kokhav Hashahar.” How did Palestinian land become a military base that then became a civilian settlement?

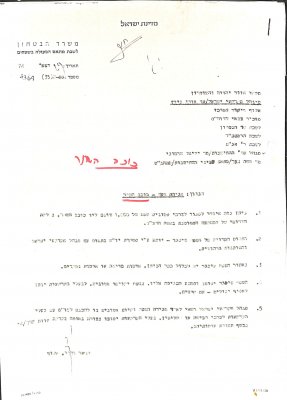

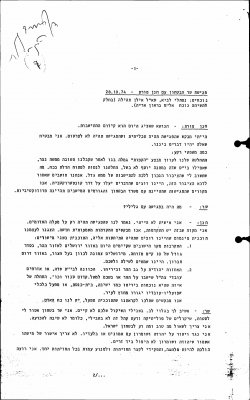

The story of Kokhav Hashahar begins with the closure of a specific area, partly farmed, near the Palestinian villages of Deir Jarir, Kafr Malik, a-Taybah and Rammun – for military training. “Approval is hereby given to close an area of 1,000 dunams near Kokhav Hashahar for the purpose of training”. This statement is found in a letter sent in December 1974 by Major General Refael Vardi, Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories to the military commander of the Judea and Samaria Area, the Israel Land Administration and the Jewish Agency. “The area to be closed should include, to the extent possible, state land or absentee land,” the letter goes on to state, adding that Palestinians who own land in the area that would eventually be closed would be permitted entry in order to harvest. The general also chose to state the obvious, highlighting that “training will take place in the area.”

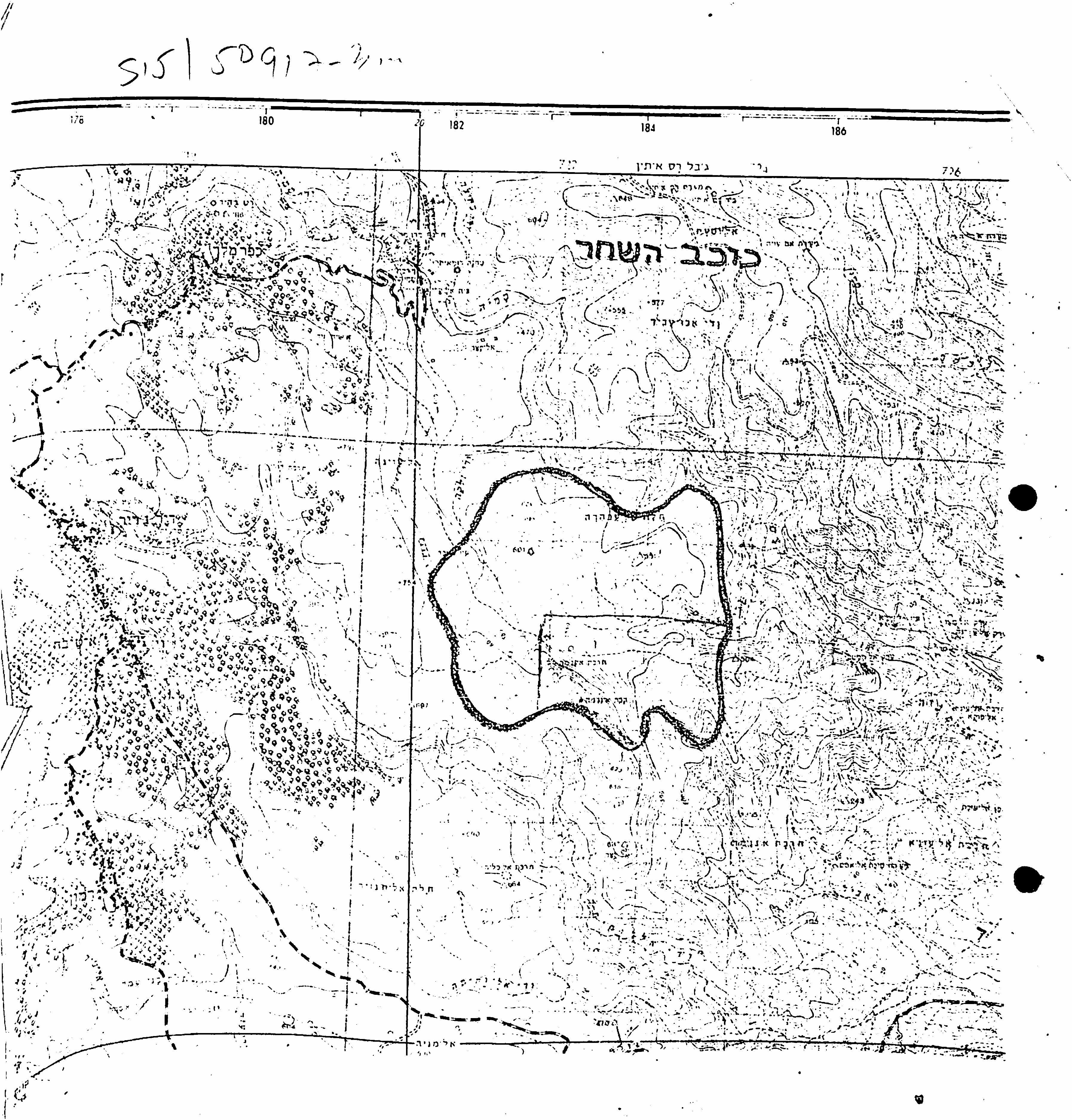

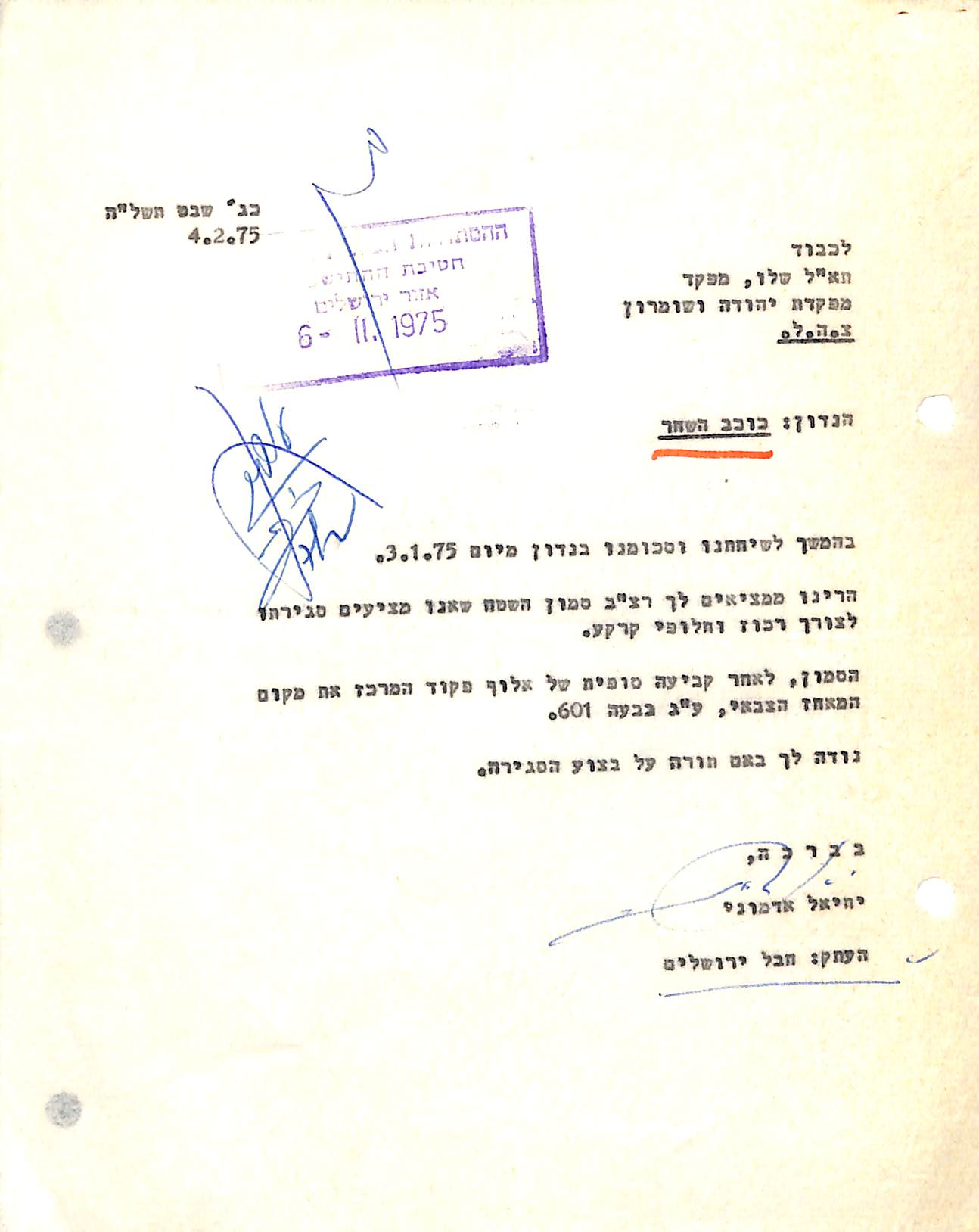

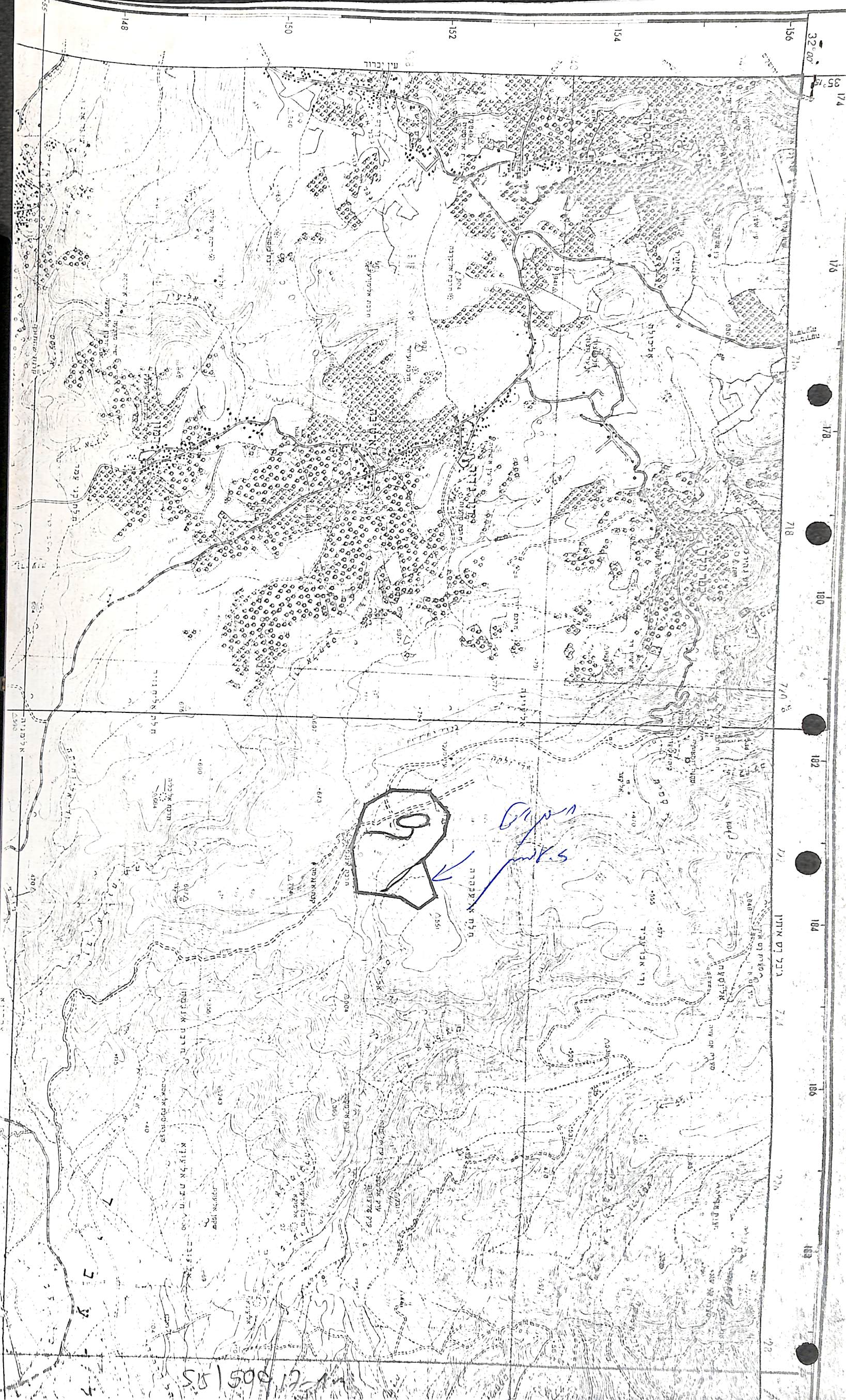

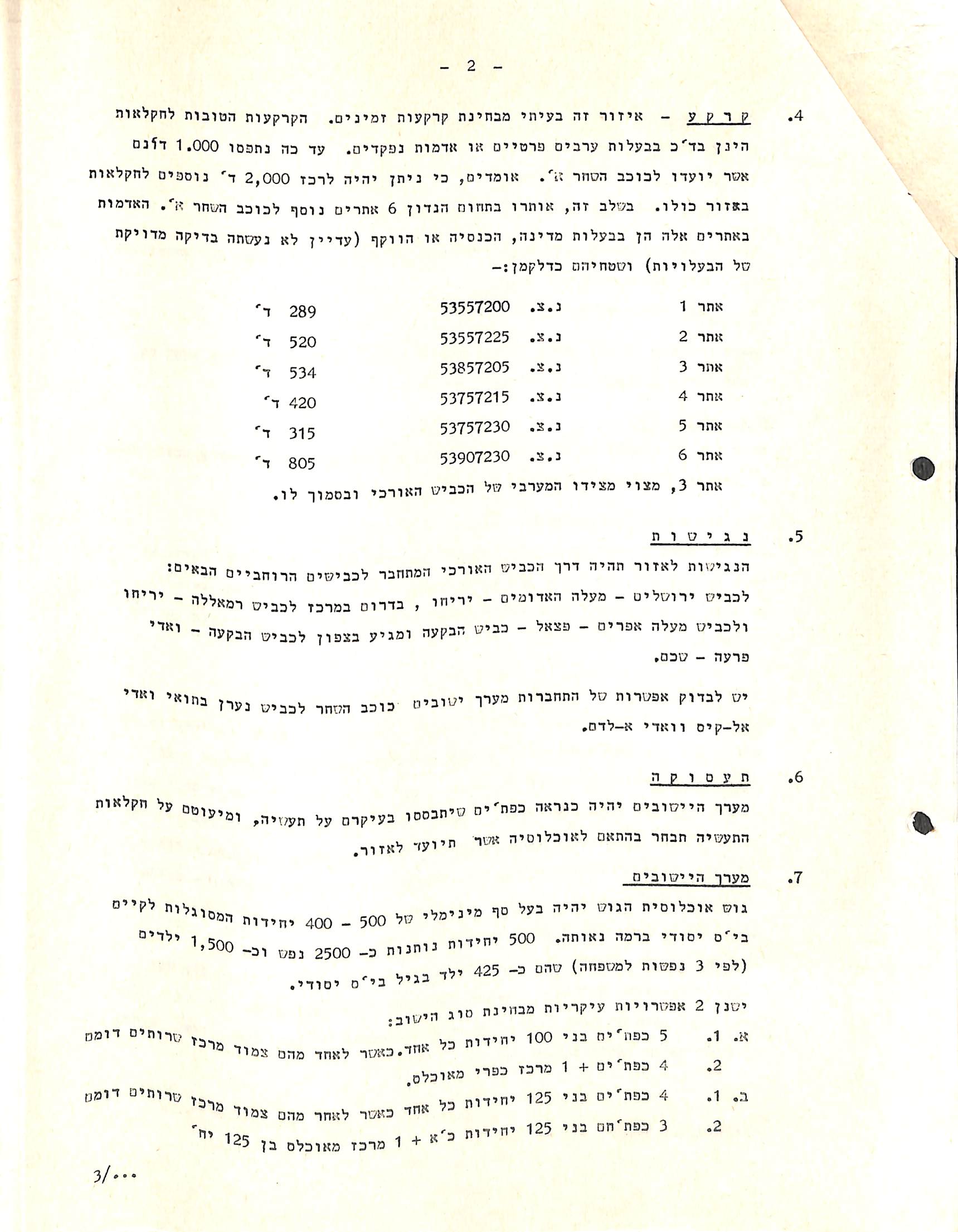

With a green light given to begin work, everyone involved sprang into action. In early February 1975, Yehiel Admoni, the director of the Jewish Agency Settlement Department, sent the Judea and Samaria Area Command a map with an outline of the area “proposed for closure for the purpose of concentration and land exchange.” The 1,000 dunam area, as ordered by the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories, included 400 dunams of rocky terrain and 600 dunams of farmland cultivated by local Palestinians. Admoni concluded his letter to the military commander with the words, “we thank you for ordering the closure.” The closure order was given, and before too long, a military outpost named Kokhav Hashahar A was set up.

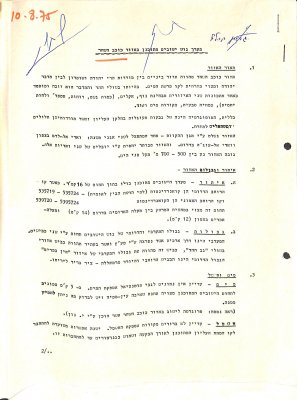

Further available documents demonstrate that the motivation for closing the area for military training and setting up a military outpost was, in fact, settlement-civilian oriented. This emerges, among other things, from a conversation between Shimon Peres, who was Minister of Defense at the time, and Hanan Porat, one of the founders of the Gush Emunim settlement movement. In October 1974, about two months before the area was closed for military purposes, Peres assured Porat, in a meeting between the two, that he favored Israel remaining in the occupied territories. “I’m against giving up Judea and Samaria with [Gush] Emunim or without it,” he said, “[I] don’t need anyone’s approval to keep Judea and Samaria from falling into foreigners’ hands.” Peres told Porat he approved settlements in Ma’ale Adumim, Baal Hazor, Tekoa and Kokhav Hashahar. In August 1975, Admoni contacted Minister Yisrael Galili, who served as chair of the Settlement Committee at the time, regarding the possibility of establishing settlements in the area, telling him the Jewish Agency Settlement Department “prefers establishing 1-2 cooperative, incorporated, rural communities” in Kokhav Hashahar.

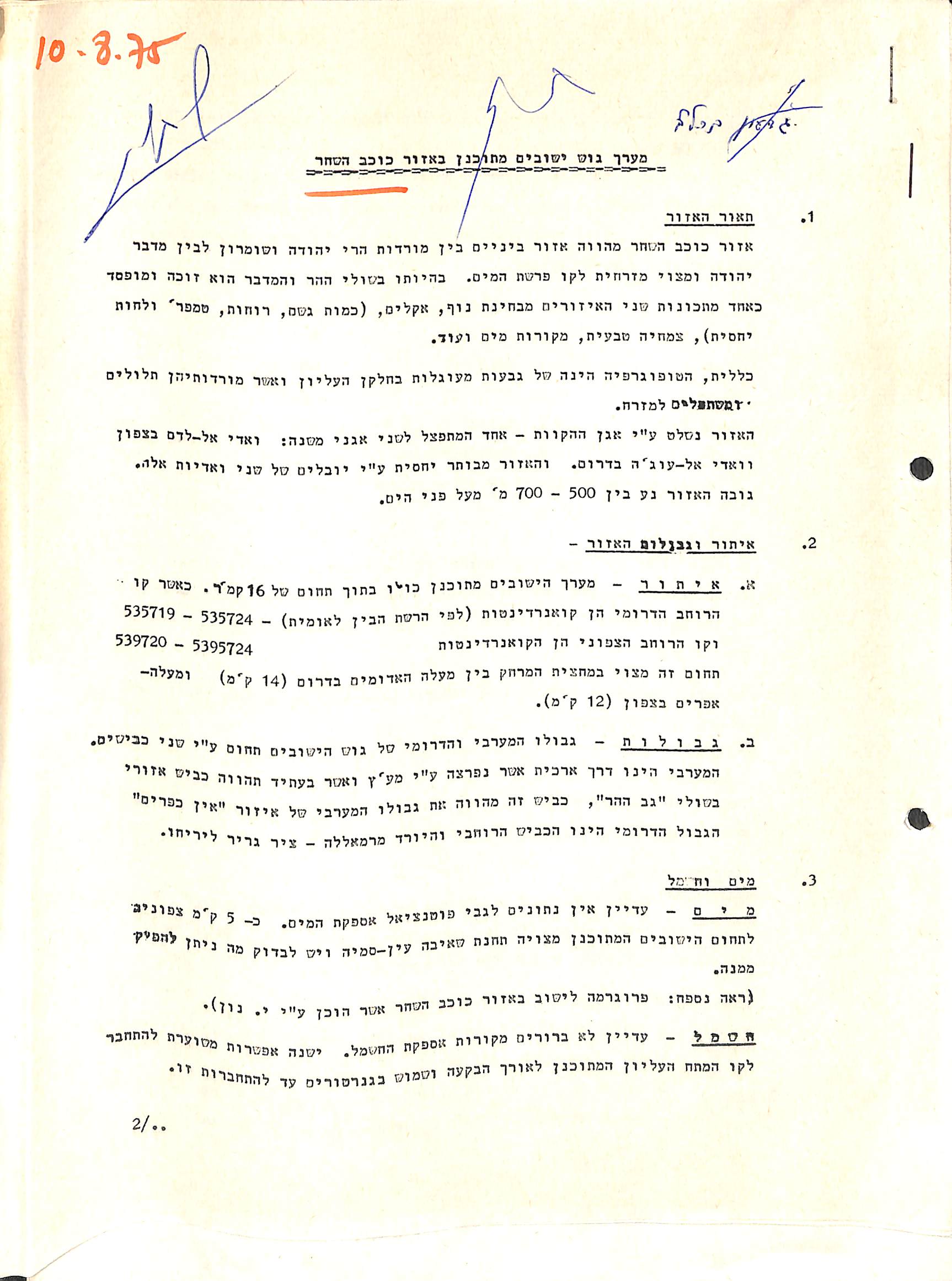

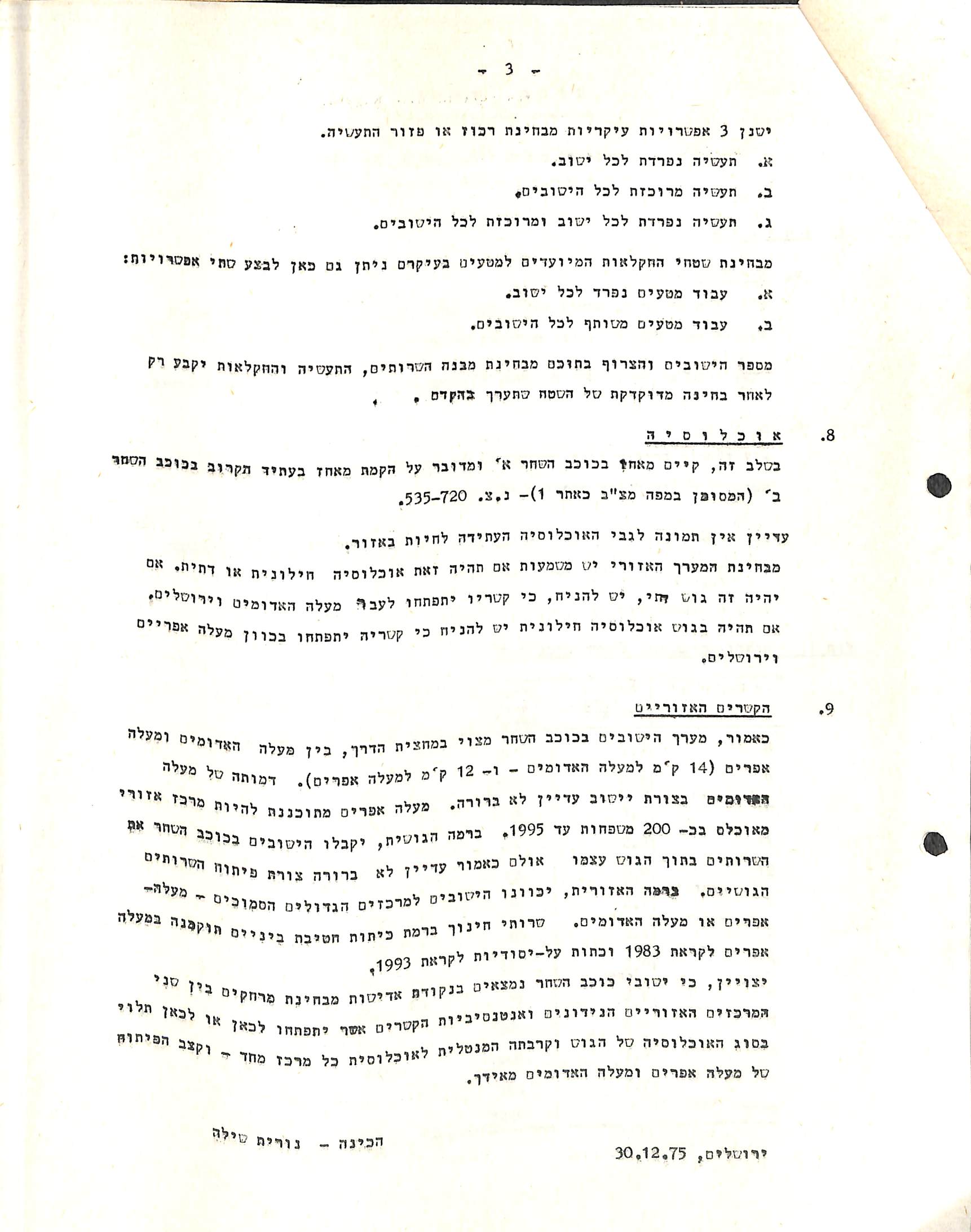

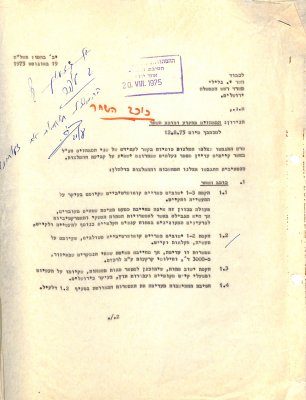

Another document from August 1975, entitled Planned Settlement Block in the Area of Kokhav Hashahar, apparently prepared by the Settlement Division of the World Zionist Organization, describes the entire area, its features, employment and settlement possibilities, connections to infrastructure and more. “The area is problematic in terms of available land,” the document states. “Good farmland is usually privately owned by Arabs or absentees.” The document mentions the area already seized, “1,000 dunams designated for Kokhav Hashahar A”, adding another outpost in that area was in the works. With respect to the future settler profile, the document states, “there is, as of yet, no picture as to the population that will live in the area,” suggesting not everyone was aware, at that stage, of the understandings between Defense Minister Peres and Hanan Porat.

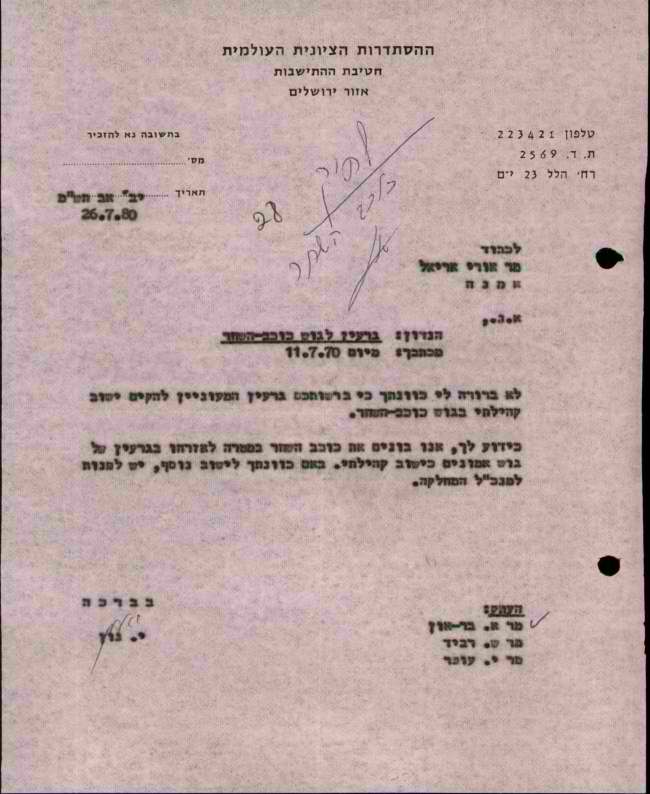

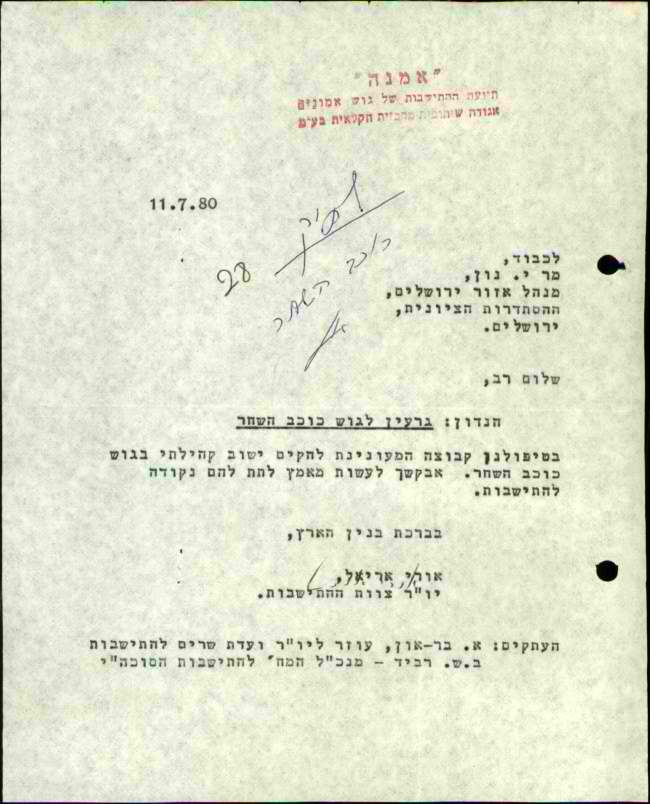

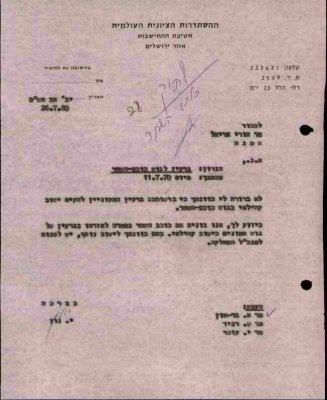

Later, in a letter from July 1980, Yishayahu Nun, the director of the Jerusalem Area in the Settlement Division, wrote, “We are building Kokhav Hashahar with a view to settling a civilian group of Gush Emunim members as a community settlement at the site.” This completed the process, and what began as a localized seizure for training grounds became the permanent civilian settlement of Kokhav Hashahar. One of many documented cases of landgrab and dispossession under the guise of security.