Israel State Archives (ISA) File GL-17005/6 from the Office of the Arab Affairs Advisor at the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) contains hundreds of pages that document some of the final chapter of the Military Government over Palestinian citizens of Israel, before it was formally replaced with civilian oversight mechanisms in December 1966. Akevot’s access to the 446-page file at the ISA was delayed for two years. We are now making it publicly available.

Israel State Archives file GL-17005/6: Operations Division/Military Government: Defence (Emergency) Regulations 1945

Israel State Archives (ISA) File GL-17005/6 from the Office of the Arab Affairs Advisor at the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) contains hundreds of pages that document some of the final chapter of the Military Government over Palestinian citizens of Israel, before it was formally replaced with civilian oversight mechanisms in December 1966. Many of the documents in this file (titled: Operations Division/Military Government: Defence (Emergency) Regulations 1945) address the changes made in how Military Government powers were exercised, and mostly, the gradual lifting of travel restrictions the Military Government imposed on Arabs in the three areas where it operated: The North, the Central Area and the Negev. The later documents in the file related to the planned cancellation of the Military Government and the transfer of its powers, as per Prime Minister Levy Eshkol’s undertaking from January 1966.

Akevot’s access to the 446-page file at the ISA was delayed for two years, initially, on the false claim that the majority of the records in the file are General Security Service (GSS) materials (“if we take GSS documents from the file only the cover will be left” an ISA staffer told Akevot), then on the vague claim that the file was classified since it related to “matters of security” – a reasoning that cannot in itself justify a denial of access request. The main portion of the file was finally declassified and opened for access, and a copy was provided to Akevot Institute only after we filed an appeal with former Chief State Archivist Dr. Yaakov Lozowick, based on the provisions of the Archive Law and Access Regulations. Even today, more than a year after most of the file was opened for public access and digitized by the ISA, it has yet to be uploaded to the ISA website. Akevot Institute is now making it available to download here.

When the State of Israel was founded, a Military Government was installed as a system for handling the Arab population that had remained in the parts of the country that were conquered but had not been designated as part of the Jewish state according to the 1947 Partition Plan. The Military Government’s objectives were to ensure a) Control over areas inhabited by Arabs; b) Control over land and villages depopulated during the war; c) Monitoring the movements and activities of the Arabs; d) Preventing refugees from returning to areas captured during the war.

The Military Government initially covered the Galilee, the Negev Desert and the cities of Ramle, Lod, Majdal (Ashkelon) and Jaffa, and, following the armistice with Jordan (April 1949), the Triangle area. Shortly after the war ended the Military Government in the mixed Jewish-Arab cities was abolished, leaving about 85% of Arabs living in Israel under Military Government rule in three districts: North, Centre (the Triangle and Wadi ‘Ara) and Negev. Sixty percent of the Arabs lived in the Galilee, 20% in the Triangle and the rest in the Negev and the mixed cities. From 1948 until its abolition in 1966, the Military Government was the main operative arm dealing with the Arab public, and as such, setting the course for Jewish/Arab relations in the country.

The source for the Military Government’s powers was the Defence (Emergency) Regulations 1945 – which had been used by the British during their mandate over the country and adopted by the Temporary State Council in 1948. The Regulations and their provisions were both the source for the Military Government’s powers, and the main tool it used in its operations.

So, for instance, Regulation 125, which played a key role in the Military Government, stipulates the Military Commander (commonly known as the Military Governor), may declare a certain area or locality as a closed zone and require anyone entering or leaving it to obtain a written permit. It was used to split certain areas within the country into closed zones, referred to as “Military Government Zones”. The Negev, the Galilee, Wadi ‘Ara and the Triangle were internally divided into different zones and residents required permits in order to travel between them, as well as to other parts of the country. The boundaries of these zones were periodically altered, and these changes were presented as “easing the Military Government” for the benefit of the residents.

The division into “closed zones under Regulation 125 served as a basis for control measures over the population. So, for instance, Regulation 109 empowered the Governor (referred to as the Military Commander in the Regulation) to issue personal “restriction orders” that would prevent their subjects from living in or accessing a certain zone. Regulation 110 provides, among other things, that the Governor may exile a person from his place of residence and place them under police supervision for up to one year (orders issued pursuant to this regulation were referred to as “exile orders”).

The military used other regulations that provide for draconian supervision and punitive measures. Regulation 111 empowered the Military Governor to place a person in administrative detention, with no trial or a formal right to appeal. Regulation 112 empowered the Minister of Defense to deport persons from Israel, including citizens.

The records in this file shed light on the policy considerations that guided the Military Government and the reasons for some of the common methods of practice it used. The many discussions around travel restrictions and frequent changes made to them attest to how central they were to controlling the population. They also provide historic documentation of the restrictions themselves – their changing boundaries, the stricter measures taken against Negev Bedouin compared to other subjects living under the Military Government, as well as samples of orders and travel permits.

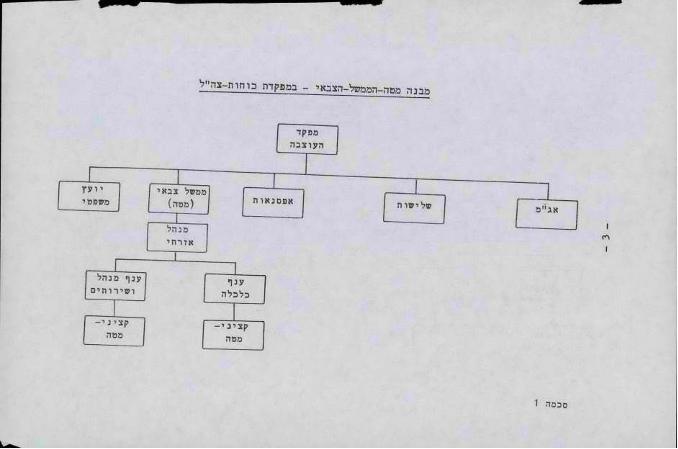

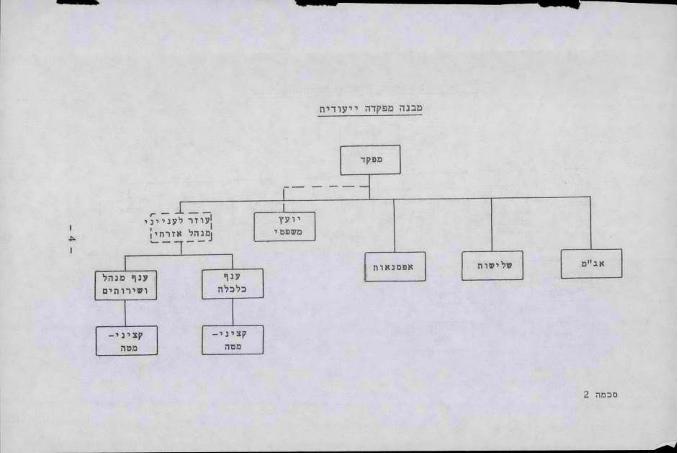

While declaratively, the Military Government was designed to maintain national security based on the Defence (Emergency) Regulations, the records contained in File GL-17005/6 offer a more accurate picture of its goals and activities in controlling Israel’s Palestinian population, its political activities and land resources, as well as the Military Government’s ultimate replacement by civilian bodies to continue this work. While oversight and control of Israel’s Arab citizens passed to civilian hands after the abolition of the Military Government, these bodies – the Arab Affairs Advisor at the PMO, the Israel Police, the GSS, and the Israel Land Administration – continued to rely on the Defence (Emergency) Regulations as the legal framework for their own supervision mechanisms. In other words, the policy that formed the core of the Military Government persisted, though the importance of its abolition as the control mechanism should not be downplayed. Statements made by the Arab Affairs Advisor at the PMO seem to support this observation, as indicated in Document No. 7. Advisor Shmuel Toledano explains that the change was mainly “psychological”, with the powers of the Military Government having been transferred to civilian bodies whose operations were expanded (as shown in Document No. 9).

A main feature in the routine discussions around the travel regime was the issue of access to depopulated Palestinian villages. These villages had been declared special closed zones, sometimes as enclaves within a larger area to which access was permitted. The guiding considerations on this issue were referred to as “land considerations”, and they revolved around two main issues: the likelihood that refugees from these depopulated villages would return to them should they become accessible and the status of the land in these villages from the state’s standpoint.

Different documents within the file reveal a list of measures Israel used to control the land of depopulated villages: Forestation (mostly of built-up areas that had not been destroyed yet); leasing for cultivation to Jewish farming communities; transfer as compensation to other “absentees”; compensation in return for removal of ownership claims; enforcement vis-à-vis construction without permits; demolition of remaining structures; expansion of IDF training grounds and the establishment of military camps and facilities; “populating and developing the Galilee” via industry and farming; declaring nature reserves and posting guards over them (see Documents 4, 5, 11).

The file also contains two lengthy documents that present the IDF’s official doctrine regarding two matters that lie at the heart of all these issues: one is a manual named “The Defence (Emergency) Regulations 1945 – Provisions and Functions”, internally published by the Military Advocate General Corps in March 1963. The first section of the manual contains an overview of the provisions in the Regulations that formed the basis for the Military Government rule over Arab citizens. The second section lists the practical objectives for which the Regulations were invoked.

Another document in the file was prepared after the Military Government in Israel ended and two years after the Military Government in the territories occupied by Israel in 1967 was established. This is a military manual, entitled Seizure of Occupied Territory and Military Governance, an IDF General Staff binding doctrinal document. The manual was used to guide the actions of military powers in exercising control over the occupied territories, based on the experience gained through the Military Government inside the country and lessons learned during the first two years of the Military Government in the territories.

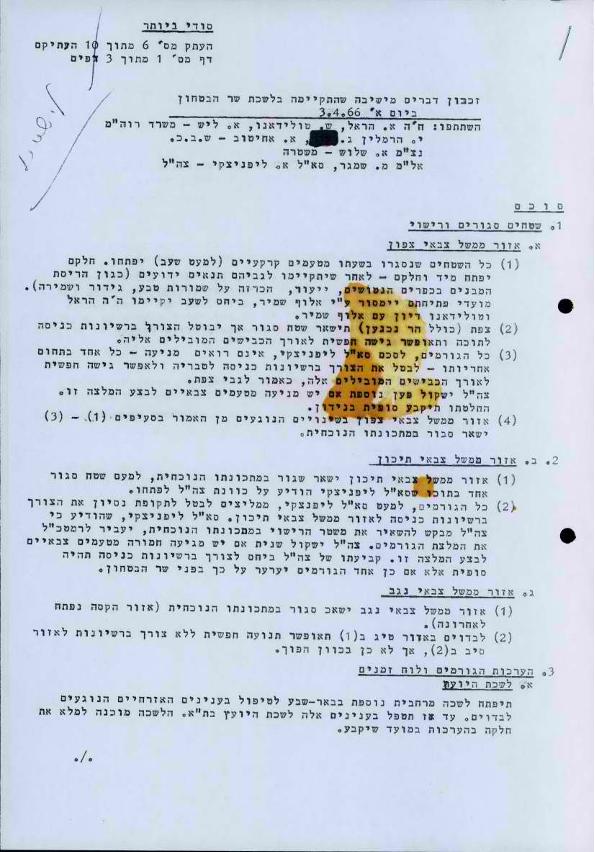

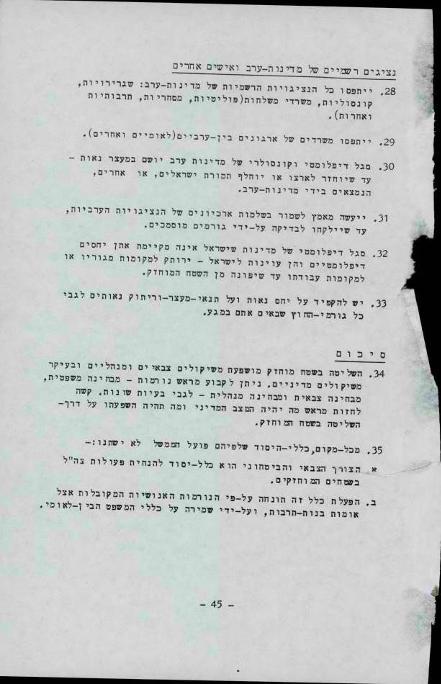

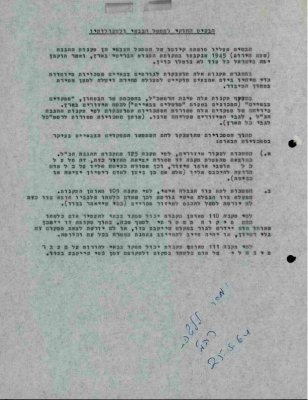

Document 1: The Defence (Emergency) Regulations 1945 - Provisions and Functions

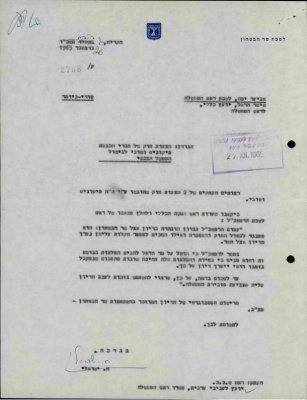

In March 1963, then Military Advocate General Colonel Meir Shamgar (signing under his previous name, Sternberg), circulated a 13-page manual that was classified as “secret.” Only 30 copies were printed, and the manual appears to have been designed for internal use by the Military Judge Advocate Corps. The first section of the manual, entitled, The Defence (Emergency) Regulations 1945 – Provisions and Functions, contained an overview of the provisions within the Defence (Emergency) Regulations that served as the basis for the Military Government over Palestinian citizens of Israel. Colonel Shamgar clarified that the manual highlights Regulations that were actually used. The second section, Paragraph 8, lists the practical objectives for which the Regulations were invoked. MAG Shamgar cautioned that “use of Paragraph 8 outside the [Military Advocate General Corps] requires command approval.

The most prominent feature of the Military Government was the travel permit regime in place for Arab citizens of the country who were living in areas declared as Closed Zones. The first chapter of the manual elucidates that the source of the power to issue orders prohibiting residents of certain areas from entering or exiting without a permit from a military officer (the “Military Commander” in the Regulations, commonly referred to as the “Military Governor”), lies in Regulation 125 of the Defence Regulations. “Such closure is what effectively distinguishes the ‘Military Government’ areas from the rest of the country”, notes the manual. To prevent movement within the closed zone itself, for instance, in order to forestall resettlement in depopulated villages, the Regulation also provides for the closures of various zones within the closed area.

The manual’s second chapter describes what needs Regulation 125 meets: Preventing Arabs from “entering and settling” in border areas in the Galilee and the Negev (thereby impeding movement of infiltrators into Israel); preventing “settlements” of “minorities” in “abandoned villages” and preventing Arabs from using land designated for settlement by Jews; preventing wide-scale migration of Arabs into areas within Israel with little or no Arab presence. Further security purposes served by the Regulation follow: providing for IDF training areas and limiting civilian movement during security alerts.

The purpose of Regulation 125, the manual states, is to prevent the free movement of “entire publics” rather than individuals. Several Regulations grant the Military Commander powers that enable monitoring individuals, including Administrative Detention Orders (Regulation 111, which was revoked once the Emergency Powers (Arrests) Law was enacted in 1979). Personal restriction orders pursuant to Regulation 109 may be used to prohibit an individual’s presence in a certain area, require them to notify the authorities of their movements, prohibit them from possessing a certain item (for instance, a car), prohibit them from employment or restrict their business affairs and social connection, or all of the above. A separate Regulation – No. 110 – empowers the Governor (“Military Commander”) to place a person under police supervision for up to a year. This Regulation allows placing an individual under “all or any” of the following restrictions, as per the decision of the Military Governor: a person may be exiled from their home to a different part of the country; a person may be prohibited from leaving the area of a village, town or district without permission from the police district commander; a person may be required to report to a police station at any time and a person may be prohibited from leaving their home after dark. Regulation 111 empowers the Governor to place a person under administrative detention, and Regulation 112 provides for deporting a person from the country, including Israeli citizens. The purpose of the powers relating to personal orders was described in Paragraph 8 of the manual. They enable “preemptive action to neutralize hostile elements quickly and efficiently”.

Under the title “administrative penalties”, the manual lists, among others, the powers of the Military Commander to confiscate a structure (or land) and demolish it if “he has reason to suspect” that a shot was fired or a bomb was thrown from the property. The power to confiscate and demolish homes applies also to any house on a street, in a quarter or in a town one or several of whose residents are suspected of certain offenses, even if said homes have no connection to the suspects. The 1963 manual notes that these provisions had not been employed since Israel’s establishment. The purpose behind the use of the Defence Regulations is clarified at the end of the document. While the editor admits the contribution the Regulations make to averting actual security threats is impossible to quantify, the overall powers the military has “and particularly the powers to close areas” have a “restraining and deterring” “cumulative effect”. These, in turn, enable the institution of a “governing system” among the Arab citizens, some of whom are hostile to the State of Israel, which is “merely an expression of the fact that some citizens among the minorities do not accept the State’s existence and a reflection of their emotional ties to neighboring countries”.

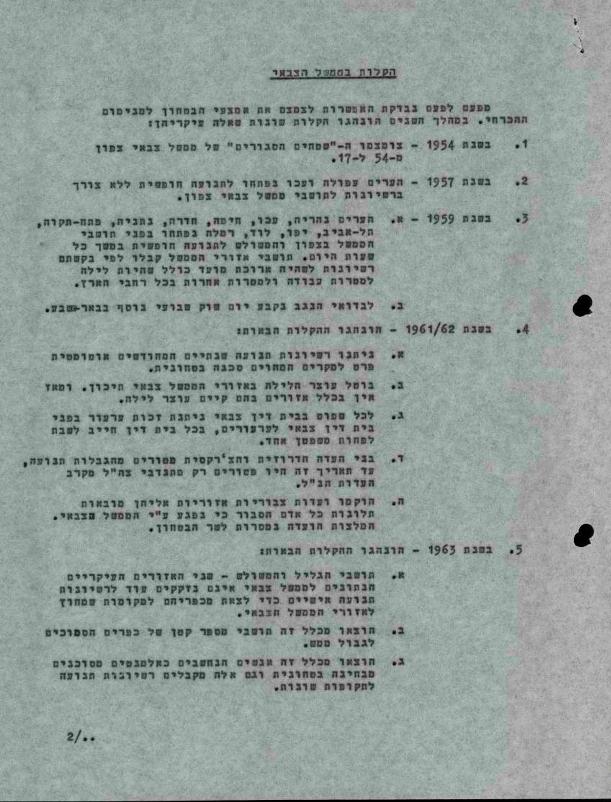

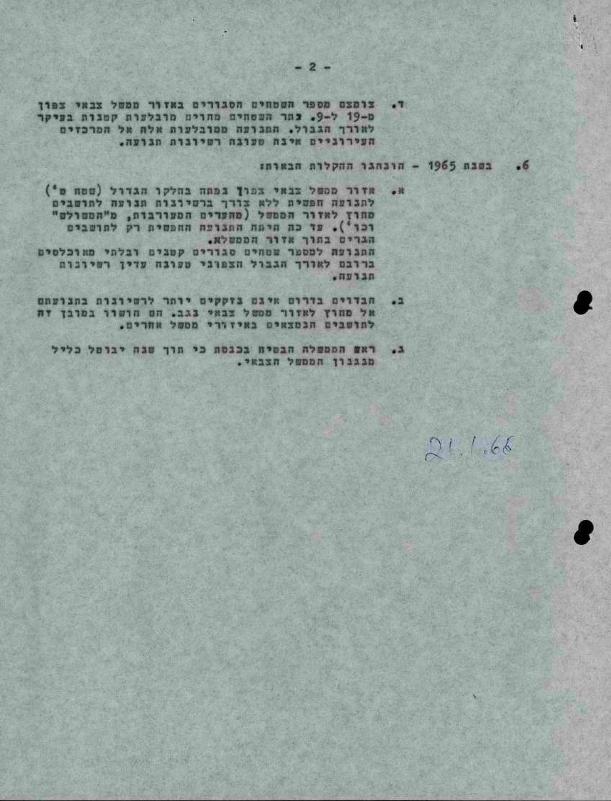

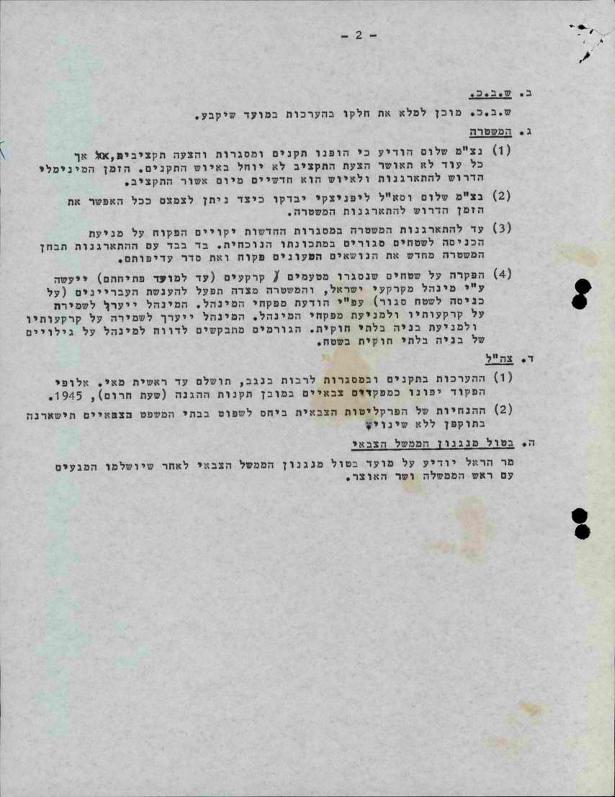

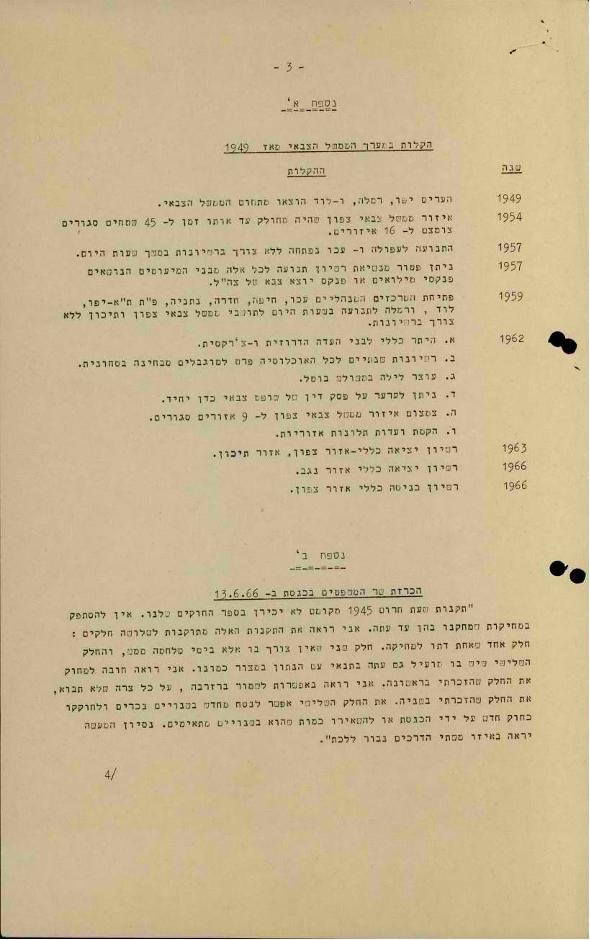

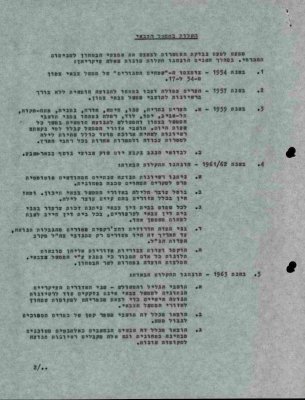

Document No. 2: Easing of the Military Government

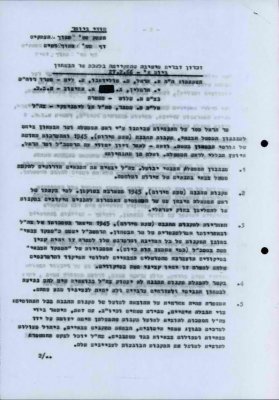

An unsigned briefing prepared by a staff member of the Office of the Arab Affairs Advisor outlines the chronology of changes made to the operations of the Military Government (referred to as “easing of the Military Government”). The file contains additional drafts of this document.

Document No. 3: Easing of the Military Government

On November 3, 1963, some two weeks after Levy Eshkol’s decision to cancel the general requirement that Arab citizens of Israel carry personal travel permits (on October 21, 1963), Chief of Staff Zvi Tzur issued a directive regarding a general travel permit. This permit allowed most people residing in Military Government areas in the Triangle and Wadi Ara to travel outside their areas of residence without a personal permit. The easing of the travel regime was not applied to residents of the Negev and of six villages in border areas. In addition, the boundaries of Military Government zones in the Galilee were redistributed such that the number of zones was reduced from 17 to nine. Under orders of the Chief of Staff, the areas of eleven “abandoned villages” remained closed for access after the redistribution.

Document No. 4: Comments for discussion of opening closed areas in Western Galilee

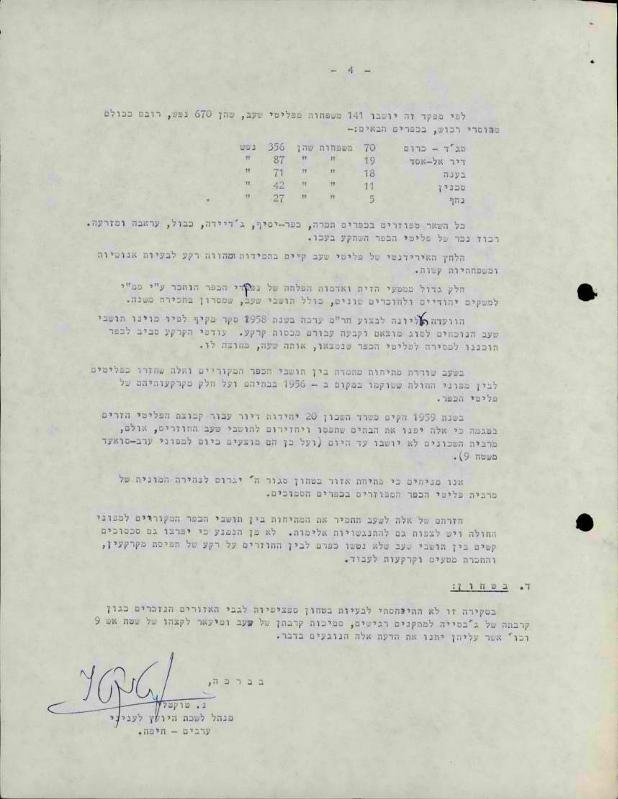

Following the Chief of Staff’s directive to reduce the number of closed zones in the Galilee and the continued closure of eleven depopulated villages (see document 3), on November 12, 1963, Nisim Tokatli, Director of the Haifa Branch of the Office of the Arab Affairs Advisor, wrote to Arab Affairs Advisor Shmuel Toledano regarding the six “destroyed and abandoned villages” and the two closed zones (Arab al-Aramsha and Sha’b) in the purview of the Advisor’s office in Haifa.

In the document, Tokatli outlines the dispersal of the villages’ displaced residents and how village lands are used. He also provides an assessment of the likelihood of refugees returning to a village if the orders regarding its closure were to be revoked. In this context, Tokatli recounts some of the measures the state had undertaken to prevent refugees from returning to their land: forestation by the Jewish National Fund, leasing of land for cultivation by Jewish communities and the transfer of land for cultivation by refugees from other communities as compensation.

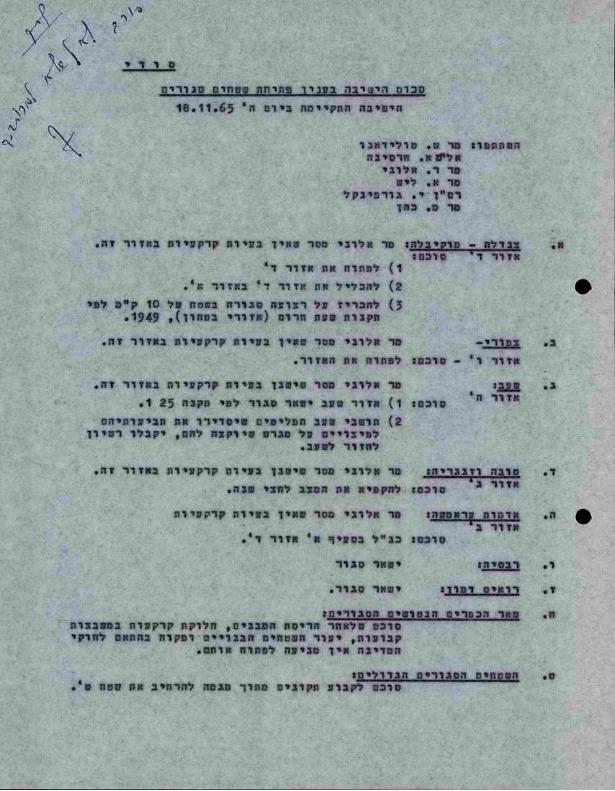

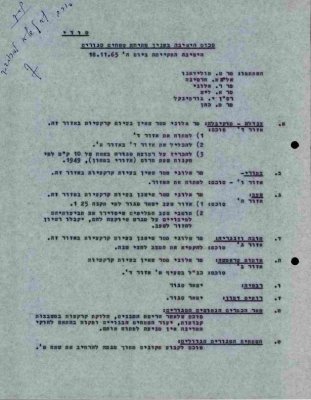

Document no. 5: Summary of meeting regarding the opening of closed zones

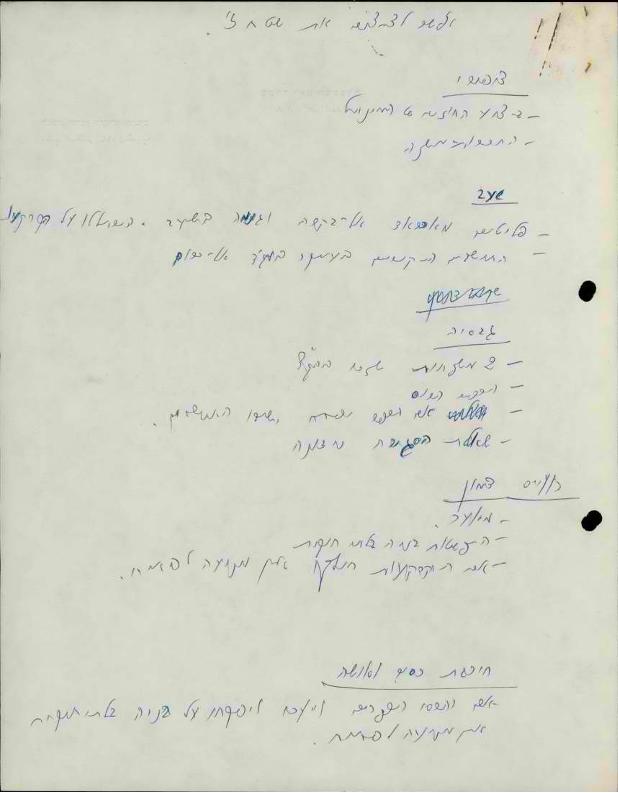

On November 18, 1965, the Office of the Arab Affairs Advisor at the PMO, Shmuel Toledano, hosted a discussion regarding the opening of closed zones within Military Government areas. Representatives of the Military Government were in attendance. This document presents a summary of the discussion and handwritten notes attached to it.

The discussion focused on nine villages, and a decision whether to keep the village under closure or allow access to and from it was made with respect to each village individually. The discussion centered on two issues, areas of depopulated villages that had been destroyed and “large closed zones”. Where the status of village lands had been regularized to the state’s satisfaction, a recommendation to open the village for access was made. Villages with outstanding “land issues” were left closed. The term “land issues” or “land considerations” featured frequently in the ongoing discussion on the closure of depopulated villages (see, documents 3, 4 and 10).

Paragraph G, concerning the areas of the “remaining abandoned villages” states that: “After the demolition of structures, distribution of land […], forestation of built-up areas and enforcement under state laws [as they were at the time], there is no impediment to opening [said areas for travel]”. The handwritten annotations attached to the summary list two more measures the Military Government used to prevent the return of refugees to their original villages: Enforcement on construction with Military Government approval and the inclusion of these areas in military training zones.

Document no. 6: Vacation in Prison

During the process of declassifying the file for public access, a letter was removed from it. Its content remains unknown, but two pages that had been annexed to the letter, were declassified. The pages were taken from a Hebrew summary of news stories in the Arabic language media in Israel. One of the stories is highlighted, suggesting it is the subject of the concealed document. Under the heading “Vacation in Prison”, on November 29, 1963, al-Mursad newspaper reported the story of ‘Ali Mohamad Mar’i Hammad from Kafr Danon, who had received approval from the Nahariya Workers Council to vacation at a convalescent facility in Zichron Ya’akov (convalescent facilities were used as vacation spots for workers). The desk clerk at the Military Government office refused to give Hammad a permit that would allow him to travel to Zichron Ya’akov. Not wanting to lose his vacation entitlement, Hammad, who “relied on his loyalty to the country” went to the facility. That night, a police officer approached him at the facility and detained him for a day and a half at the police station. Years later, Mar’i told television documentary series Tekuma that he was tried at the Military Court in Nazareth and ordered to pay a fine of two Israeli pounds.

Some of the other news stories concerned a suspended sentence imposed on a farmer who insisted on his right to cultivate his land which had been confiscated to build the city of Carmiel; complaints from Arab tobacco growers regarding discrimination compared to Jewish growers and protest from the Druz Religious Council in Dalyat al-Karmel over the authorities’ establishing religious tribunals without consulting Druz residents and based on political party considerations. A public statement issued by the religious council and quoted in al-Etihad newspaper read: “Are the residents of Dalyat al-Karmel, Beit Jann and al-Maghar second class citizens like in South Africa”?

Document no. 7: The legal basis for the Military Government and its actions

The document describes the legal basis for the operation of the Military Government: The Defence (Emergency) Regulations and the appointment of “military commanders” (commonly known as “military governors”, which the document stresses is an error) to certain areas. The document also describes the main powers used by the military commanders: the power to close areas (under Regulation 125), the power to issue personal restriction orders (Regulation 109), placing individuals under police supervision for a year (110) and placing individuals in administrative detention (111).

The document is neither signed nor dated, but was presumably prepared at the Office of the Arab Affairs Advisor. A written annotation states it was “delivered to the PMO on May 25, 1964”.

Document no. 8: Bills sponsored by MKs Mikunis and Toubi for the abolition of the Military Government

Over the years in which the Military Government was in place, Members of Knesset (MKs) from various factions, including Herut, General Zionists, National Religious Party (Mafdal), United Workers’ Party (Mapam) and Israel Communist Party (Maki), sponsored bills for its abolition and for the repealment of either the provisions in the Defence Regulations on which it relied or the Regulations in their entirety. In the attached document, Defense Minister Aide Haim Yisraeli informs PM Levy Eshkol’s Political Secretary, Aviad (Adi) Yaffe of the Chief of Staff’s response to two bills sponsored by Maki MKs Shmuel Mikunis and Tawfik Toubi. The explanatory notes for one of the bills read: “The Military Government, which is based on the Mandate-era Defence Regulations defies the principle of civil equality, violates the national rights of the Palestinian population and undermines the foundations of democracy in the country. It must, therefore, be abolished”.

The position of Chief of Staff Zvi Tzur, as relayed in Yisraeli’s letter, was that the Military Government must remain in place but should be eased further. About two weeks later, on January 12, 1966, the Prime Minister announced at the Knesset that the government was planning to abolish the Military Government within a year.

Document no. 9: Minutes of a meeting held at the office of the Minister of Defense on Sunday, February 27, 1966

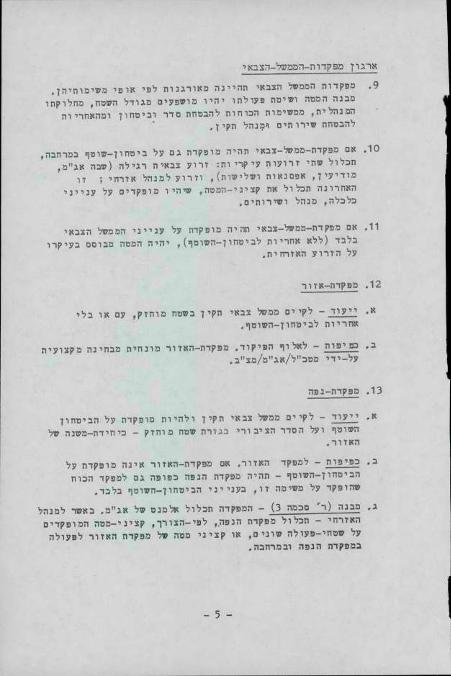

On Sunday, February 27, 1966, PM Advisor Isser Harel informed representatives of the Israel Police, the GSS, the IDF and the Military Government of the directives issued by the Prime Minister and the Defense Minister “regarding the Military Government, the status of the Defence (Emergency) Regulations 1945 and the redeployment of security forces on the ground”. At this meeting, operative measures for coordination between the various security agencies once the Military Government ended its operations were discussed and agreed upon.

The directives issued by the Prime Minister and Minister of Defense which are listed in the meeting minutes instruct the dismantling of the Military Government apparatus, while the Defence Regulations would remain in place. The powers to run the Military Government would be transferred to the IDF, while the powers of the military governors would be handed over to the IDF generals in command of various sectors. The powers to invoke and enforce the Emergency Regulations on residents of the areas was handed over to the Israel Police, and in cases so decided, to the GSS.

The directives indicate that the decision to revoke the Military Government included an expansion of enforcement agencies on the ground: GSS forces would be reinforced, police stations and headquarters would be added, a special police reserve unit would be established for “quick, effective interventions in areas of mixed communities”, the Israel Land Administration would make preparations to tackle “illegal construction”, structures that fall into this category would be demolished and a special unit would be set up for these purposes.

In addition to these measures, two more methods to maintain control on the ground were emphasized: sustaining the Military Government’s deterrent effect through increased IDF presence in the Galilee, achieved by expanding training grounds and building military camps and facilities “as much as possible”; and stepping up “settlement and development in the Galilee”, for instance, through industrialization and expanding farming as much as possible.

The directives list how the various powers of the Military Government, including use of the Defence (Emergency) Regulations would be divided among various agencies: the Israel Police, the GSS, the IDF, the Arab Affairs Advisor and the Israel Land Administration. The IDF retained control of the Negev, south of the “Siyag area” [restricted area – the Negev area designated for the Bedouin].

During the meeting, Harel asked the various agencies to reassess their policy on the closure of areas for travel and issuance of personal restriction orders with a view to reducing these. The representatives were asked to provide Harel with the results of the reassessment. A summary of the reassessment appears in Document No. 10.

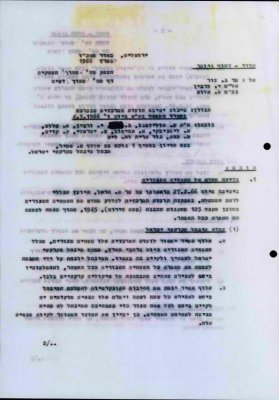

Document no. 10: Summary of Central Committee meeting held at the Military Government Office in Tel Aviv on March 4, 1966

On March 4, 1966, the “Central Security Committee” held a meeting in preparation for the abolition of the Military Government in Israel. The committee, commonly referred to as “the Central Committee”, coordinated Military Government policy and its membership included representatives from the office of the Arab Affairs Advisor at the PMO, the military, the GSS, the police and the Military Government itself.

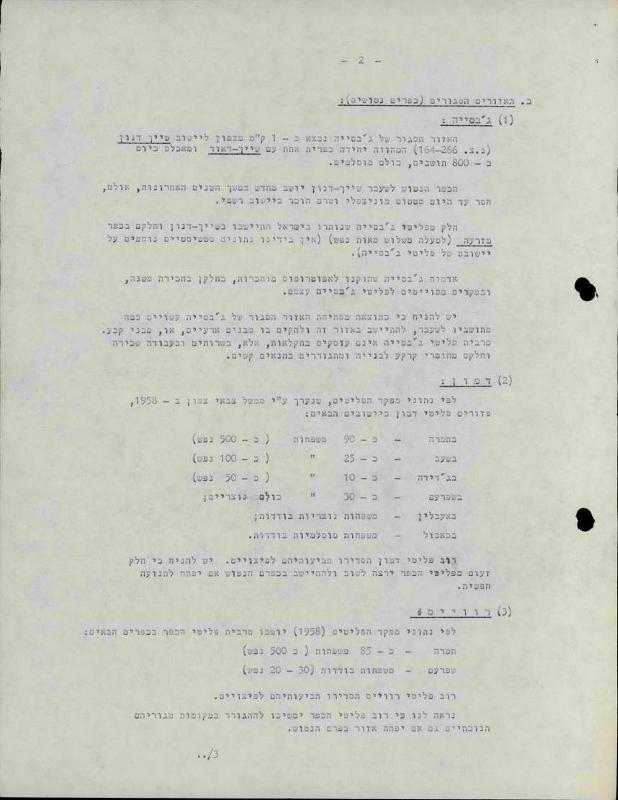

Two major issues were on the agenda: Policies to reduce “closed zones” within Military Government areas and principles for use of personal restriction orders under Regulation 109 of the Defence (Emergency) Regulations 1945.

The recommendations the agencies gave regarding closed zones tended to include significant steps toward reducing travel restrictions. The police, for instance, recommended revoking the requirement to obtain permits to exit closed zones, adding that if this position were rejected, it would recommend canceling closed zones altogether. The GSS deferred providing its recommendations on this issue, though it insisted on travel restrictions in principle: “The Service is of the opinion that some sort of permit regime [should] remain [in the closed zones]”.

The Israel Land Administration stated its position on the issue would be determined by “land considerations exclusively”. This term alluded to the possibility of refugees returning to their places of origin should closure orders affecting depopulated villages be removed and to the question of regularizing the status of village land prior to opening the villages for access. These questions were addressed in previous decisions regarding the closure of these areas. On this issue, see documents 3, 4 and 5.

With respect to personal travel restriction orders, GSS and police criteria for using restriction orders under Regulation 109 were provided. According to the document, between 50 and 100 Arab citizens whose personal travel restriction orders were set to expire once the Military Government was abolished would come under new personal restriction orders issued by the GSS. One of the general criteria listed by the GSS for use of personal orders stands out – leaders and parliamentary candidates of the leftist movement and political party al-Ard (the land). Membership in al-Ard was cause for arrest in and of itself.

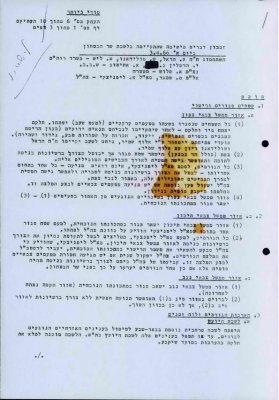

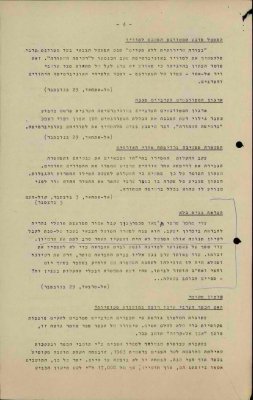

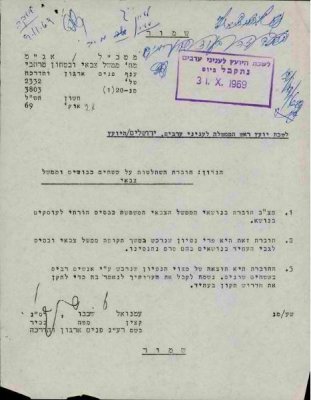

Document 11: Minutes of a meeting held at the office of the Minister of Defense on Sunday, April 3, 1966

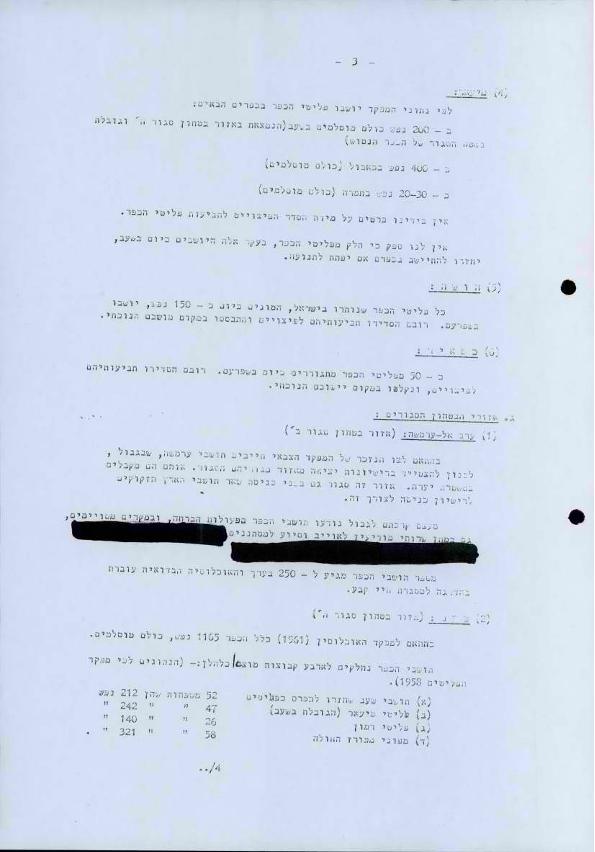

On Sunday April 3, 1966, a meeting was held at the office of the Minister of Defense to discuss reducing travel restrictions on Arabs and review readiness for this change by the implementing agencies: The Office of the Arab Affairs Advisor, the GSS, the Israel Police and the IDF. The meeting was chaired by PM Advisor Isser Harel as part of the preparations for the planned abolition of the Military Government, announced in January of that year by PM Levy Eshkol.

The meeting minutes list what restrictions would be lifted and what restrictions would remain after the changes in the three Military Government districts. With respect to the northern district, the decision was that “all zones previously closed [therein] for land reasons (with the exception of the Sha’b zone) will be opened [for travel]”. The change would apply to some areas immediately, and to others “after stated conditions are fulfilled”. The conditions were specified: “Such as demolition of structures in abandoned villages, forestation, declaration of nature reserves, fencing and guarding”.

In this context, the term “land reasons” refers to the status and future of Palestinian villages destroyed by Israel from 1948 onwards, as can be gleaned from Documents 1, 2, 3. The main test questions regarding “land reasons” were whether refugees from the villages were expected to return should the closed zone orders be revoked and whether the status of the land had been regularized to the state’s satisfaction.

Travel restrictions in the Center and Negev districts of the Military Government remained unchanged. The IDF representative, whose objection blocked the recommendation of the other officials at the meeting to revoke the requirement for permits to enter the Center Military Government District (the Triangle), was asked to reconsider.

The second part of the document centers on the division of power between various government agencies and their readiness for the IDF pulling back from running various aspects of the Military Government. Along with the changes, the meeting produced the following decision: “MAG Corps directives with respect to adjudication in military courts shall remain in effect without change”.

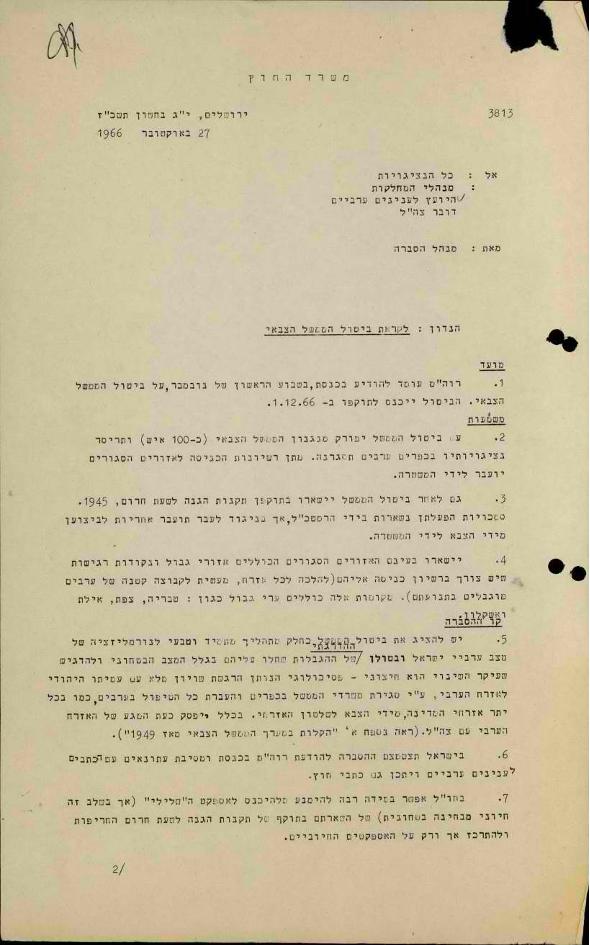

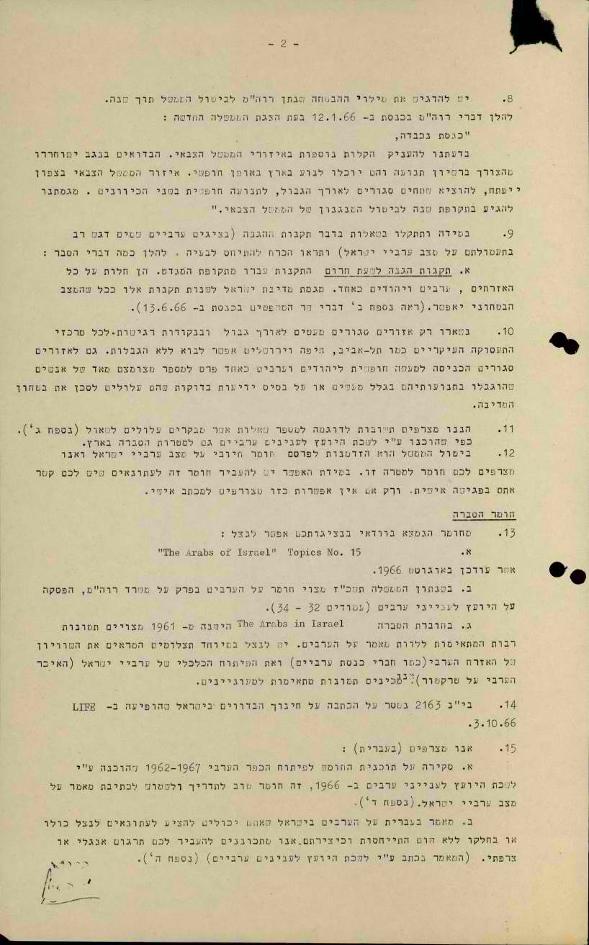

Document no. 12: Ahead of the abolition of the Military Government

On October 27, 1966, ahead of PM Levy Eshkol’s scheduled declaration of the abolition of the Military Government beginning December 1966, the director of public diplomacy at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs released a set of directives on how to present the measure. The directives in this document were sent to all Ministry of Foreign Affairs mission offices and their department heads, to the PM Arab Affairs Advisor and to the IDF Spokesperson. These directives are based on a discussion held three days prior (October 24), during which the PM’s Arab Affairs Advisor, Shmuel Toledano, outlined the “public diplomacy strategy” for the abolition of the Military Government. Toledano explained: “With the abolition, the entire Military Government apparatus will be dismantled and its twelve offices will be shuttered. […] The Arab citizen will no longer have any contact with the IDF. This change should be viewed mostly as a psychological issue of giving the Arab citizen a feeling of equality.”

Before delving into the directives, the document clarifies the practical meaning of dismantlement of the Military Government apparatus. Paragraphs 2-4 clarify that “the Defence (Emergency) Regulations 1945 will remain in place even after the abolition of the Military Government”, and the main change would be the police taking over the utilization of the Emergency Regulations and travel permits from the Military Government and the IDF.

The directives instruct to highlight the fundamental aspect of removing the need for Palestinian citizens of Israel to come into contact with military officials regarding their civilian affairs and to present the dismantlement of the Military Government apparatus as part of a trend toward bringing the status of the “Arab citizen”, to use the language of the document, on par with that of the Jewish citizens and reducing use of the Defence Regulations.

At the same time, the public diplomacy director instructed to try and “avoid getting into the ‘negative’ (yet currently essential for security) aspect of the severe Defence (Emergency) Regulations remaining in effect, and focus exclusively on the positive aspects”.

And surely, the document does state that “there is no connection between the decision to dismantle the apparatus of the Military Government and future decisions made regarding the Defence Regulations or closed zones”. The main benefit to “the Arab citizen in Israel from the dismantlement of the Military Government apparatus” was meant to be psychological: to contribute to a sense of equality and to the Citizen’s “contentment”.

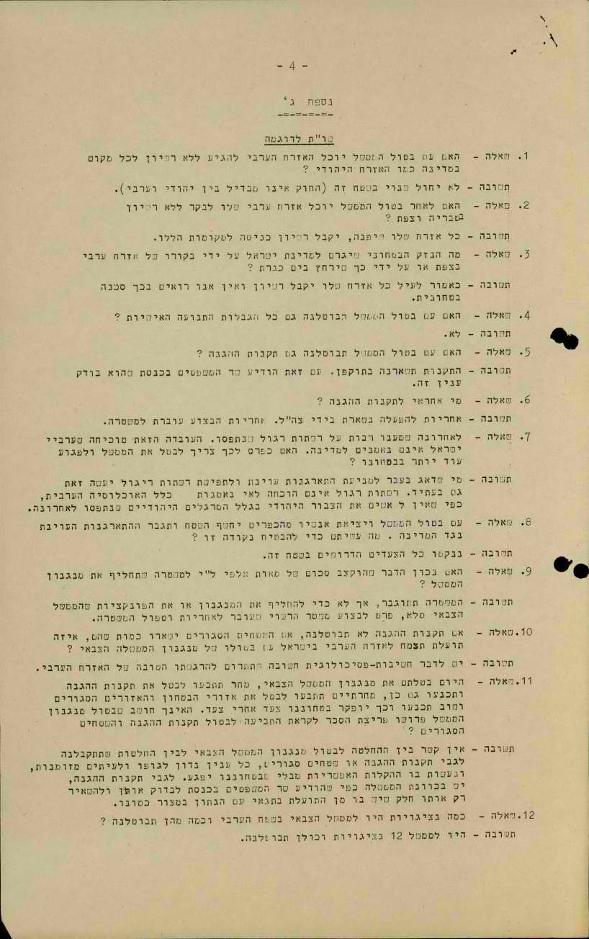

The directives document contains two annexes. The first lists “Steps to Ease the Military Government since 1949” and the second contains a list of possible questions about the topic and the responses, prepared by the Office of the Arab Affairs Advisor.

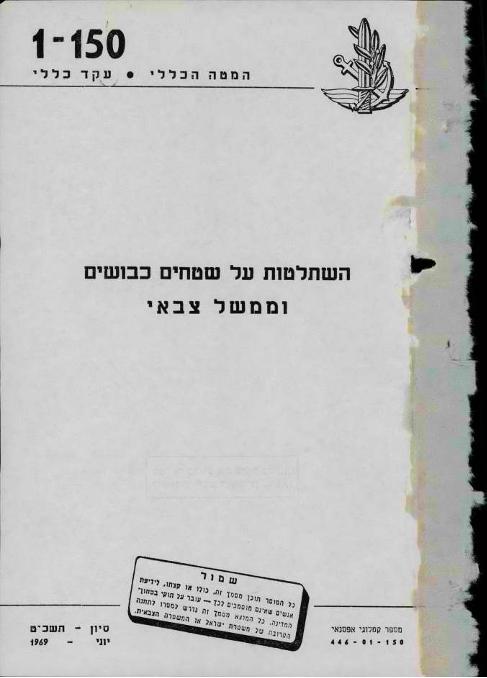

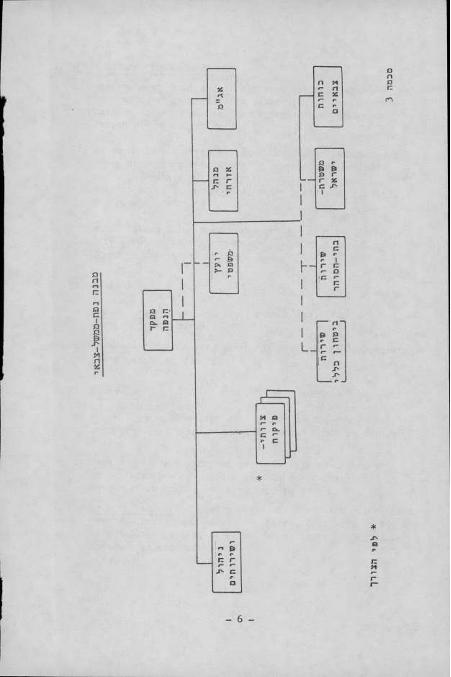

Document no. 13: Seizure of Occupied Territories and Military Governance

The manual entitled Seizure of Occupied Territories and Military Governance was published by the IDF’s General Staff in June 1969. The manual compiles the IDF’s combat doctrine on the matters cited in the heading after the first two years of occupation in the Golan Heights, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and the Sinai. The stamp on the back of the manual’s front cover clarifies: “this volume is binding upon the IDF in accordance with the directives of the senior command 1.0105”. The lessons of the occupation in the territories seized in 1967 warranted reissuing the manual, which replaced a previous edition from 1960.

The object of the publication, as indicated by the authors, is to “provide essential directives on taking over occupied land through the different phases in terms of security and control, civil administration and relations with the population and to institute the modes of operation to be pursued”.

True to this statement, the manual provides an overview of the various fields related to the military’s running and managing the occupation and the population. The document sometimes veers away from experiences gained. The section entitled “Occupation of Capital Cities”, for instance, addresses the possibility of toppling the regime in Israel’s neighboring countries.

The combat doctrine presented in the manual encompasses policy aspects, strategy and tactics – from mapping out the legal framework and principles for use of force, to presenting the structure of the governing institutions, typical measures for seizing control and principles for controlling a variety of aspects of civilian life, to listing highlights for the use of specific means of control, such as curfew, searches or roadblocks.

The manual’s combat doctrine displays an ambivalent approach to international law. On the one hand, it clarifies that all actions taken by the occupying army are based on the rules of international law, and “particularly Article 43 of the Hague Regulations concerning the Laws of War… and Articles 64-66 of the 1949 [Fourth] Geneva Convention” (page. e). The manual refers to these laws elsewhere as well. On the other hand, the manual contains directives that contradict some of the aforesaid provisions of international law, such as using deportations, travel permits and commerce licenses to deter and pressure the occupied population as a whole and individuals inside it (pp. 29-31).

The manual sets down principles that are visible in fundamental elements at the core of the military occupation of the West Bank to this day, such as the existence of a permit regime and the Military Government’s interest in the continued operations of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) (pp. 43-44).

Palestinian politics takes two forms according to the manual: It is either political resistance that must be suppressed or “local governance” designed to enable the efficient delivery of public services and “relieve the IDF of the need to care for the needs of the population”, facilitate contact with the population and maximize its cooperation with the Military Government. According to the manual, the Military Government decides who sits on local councils and “directly supervises” their activities. With respect to the political leadership, the manual states that “key figures who are activists in the held territory” must be handled with a combination of “efficiency, decisiveness, assertiveness (where necessary) and proper care” (p. 32).

This subjugation of the occupied population’s internal political arena to the military regime and its needs complements the directives to suppress both violent and non-violent resistance, joining together to constitute a complete ban on any expression from the occupied population that could be suspected as resistance to the regime in the occupied territory.

The military governance doctrine presented in the manual grew out of the experience gained in the years of Israeli control over the occupied territories, which, in turn, largely relied on the experience of the Military Government over Israel’s Arab citizens, to which it refers specifically. However, its language remains general enough to apply to any regime of occupation, so long as the relevant provisions of international law remain in place.