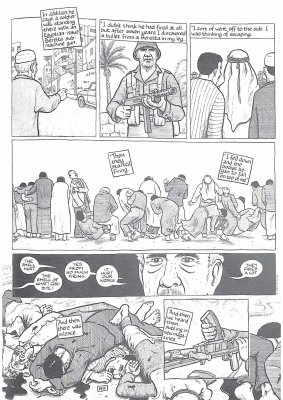

Precious few archival records about the bloody events that took place in the Gaza Strip immediately after its initial occupation in 1956 are accessible to the public. In the absence of reliable, accessible records, the events were described in a fictional story penned by author Matti Megged and published in the Lamerhav daily newspaper. The story depicts, in great detail, the exploits of “Mr. D.” a military governor dreamed up by Megged, and in an English language graphic novel by author and illustrator Joe Sacco, published in 2010. But, what is really known about these atrocities? And why are the records still sealed in Israeli archives?

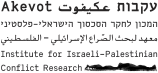

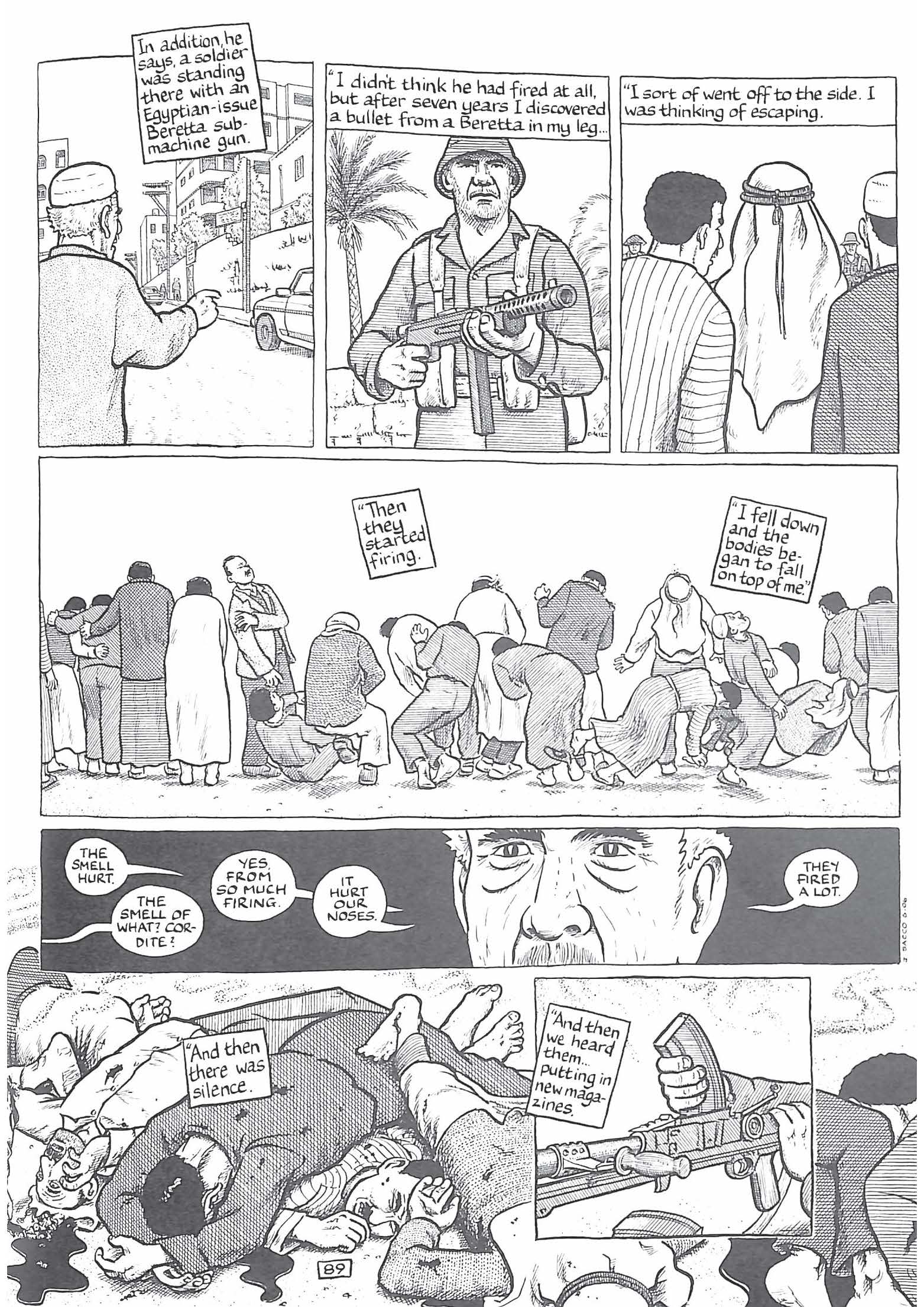

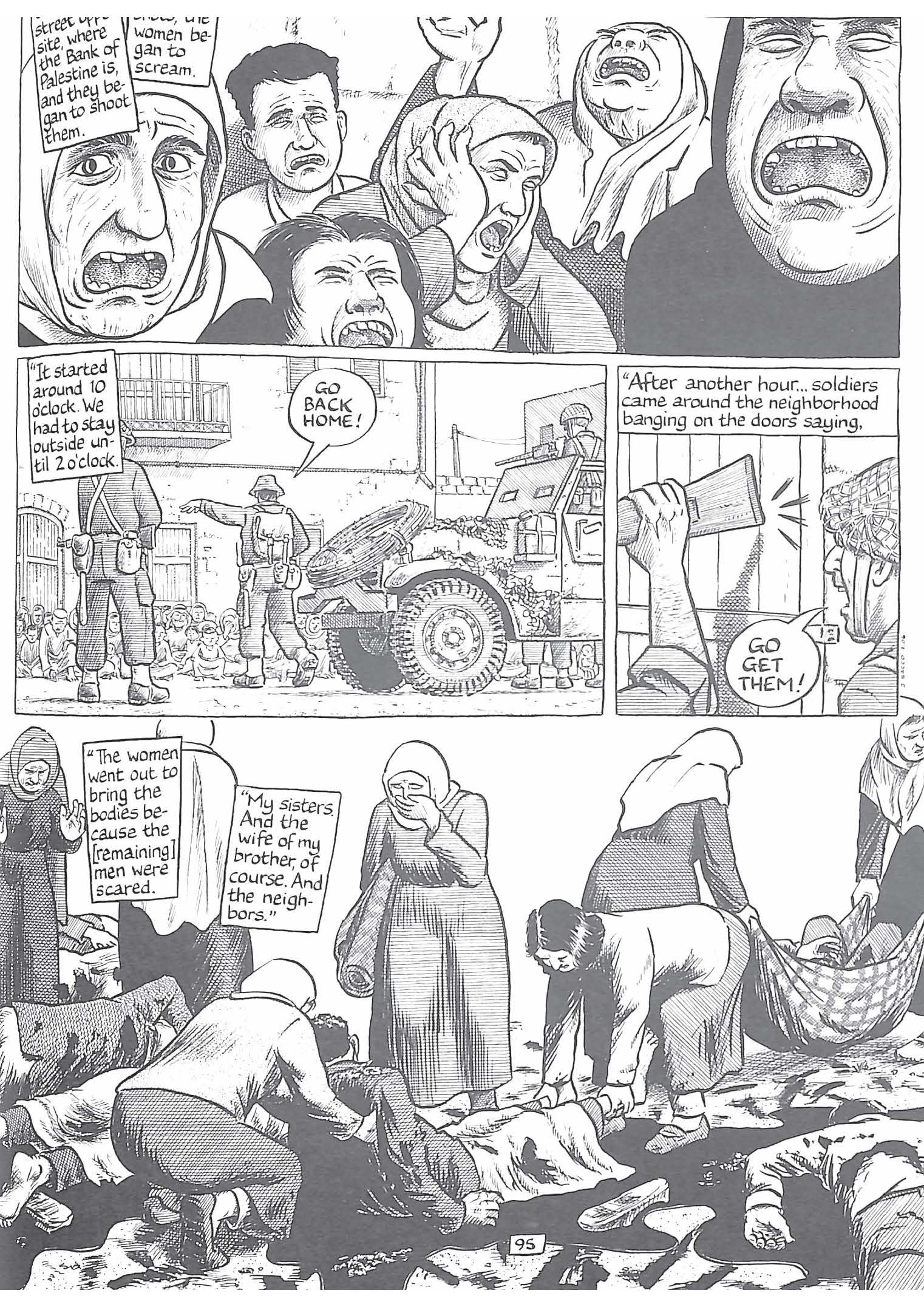

The two massacres served as the basis for a graphic novel illustrated and written by Joe Sacco, entitled Footnotes in Gaza. Sacco, author of several outstanding and award-winning graphic novels, has dealt before with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Footnotes in Gaza investigates the events based on testimonies Sacco collected from Gaza residents about the two incidents, as well as historical records from various archives.

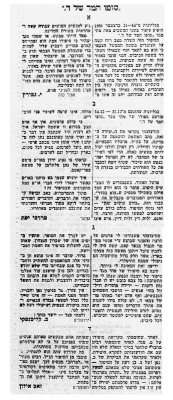

Mr. D.’s End

Several weeks after the occupation of the Gaza Strip, author Matti Megged published a short story in Lamerhav, the Ahdut Havoda Party newspaper, entitled Mr. D.’s End. The story depicts the deeds of Military Governor D. With a sharp pen, in a critique uncommon in the landscape of Hebrew literature of the time, Megged declared that it was the Israeli occupation and its military rule that caused the moral corruption of Governor D. and his subordinates. “Better-known works critical of the War of Independence – such as “Khirbet Khizeh” by S. Yizhar, and “The Other Side of the Coin” by Uri Avnery – pale in comparison to Megged’s vivid and brutal descriptions. The mounting corruption of Governor D. is the axis that drives the plot in this story. At its center is his consent to the acts of rape and massacre committed by Israeli Defense Forces soldiers. The story begins with a “brown-skinned girl, bare to the waist” who receives various guests at the house of the governor, who in turn offers her up “to every respectable guest … and everyone, like you [i.e., the guest], feels a little ashamed at first, but then gets used to the idea … Everyone gets used to it.” The rape of Gazan women by IDF soldiers repeats itself, and one soldier tells his friend: “You should have seen what was going on here last night … Those dirty Arabs, after we took their women away for work, began to riot. So what did we do? We led some women, the younger ones, to one of the houses, and threatened the men that if they did not stop, we would rape them all in front of their eyes … Do you think it had no effect? Of course it did … but it did not prevent us from doing what we promised, even though they stopped the rioting … we kept them there every night.” The governor, the soldiers said, did not care “if we went wild.”

Mr. D.’s End

Publication of the story caused a stir. Yitzhak Gvirtz, an IDF General Staff officer in Gaza at the time, responded in Lamerhav that the narrative created “a difficult mood among the workers in the (military) administration,” because the story “came to describe a situation as if it had taken place in the occupied territory.” Following inquiries to the newspaper, the editors clarified that publication of the work had been “done without sufficient consideration.” Megged stated in response that the story was fictional, although he added that “in every area of military administration there is danger of a process occurring similar to that which the ‘heroes’ went through.”