The questions of civil status of East Jerusalem residents and the fate of property they owned on both the east and west sides of the city were interwoven from the very beginning of the discussion around the implications of annexing the Old City and the villages in its vicinity to the State of Israel. Some of the records pertaining to this discussion during the first year of the occupation are presented here.

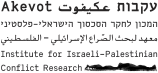

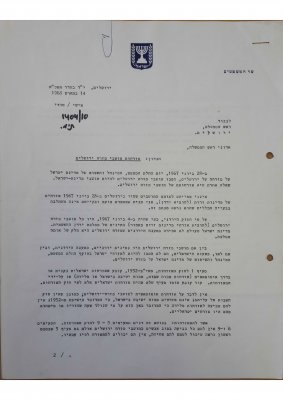

Report on the meeting of the Ministerial Committee for Jerusalem

On June 21, 1967, the Ministerial Committee for Jerusalem discussed what the annexation (in this documents referred to as “addition”) of the Old City and its vicinity to the State of Israel would mean. Sections 7-8 in a report prepared by one person who attended the meeting, then Military Advocate General Meir Shamgar, addressed the issue of the civil status and property of residents of the area designated for annexation.

Shamgar noted that despite the application of Israeli law to East Jerusalem, local residents were not expected to be considered Israeli citizens due to the Citizenship Law. This law sets several conditions for granting Israeli citizenship, including living in Israel for three years and some knowledge of Hebrew.

On the status of the residents’ property, Shamgar noted that under existing statutory provisions, East Jerusalem residents could be considered ‘absentees’, and their property, even at their possession in East Jerusalem, might be considered ‘absentee property’. A change would be needed, Shamgar wrote, that would prevent their being considered absentees on the one hand, but, on the other, preclude any claims on their part to have their pre-1948 property located in west Jerusalem returned to them.

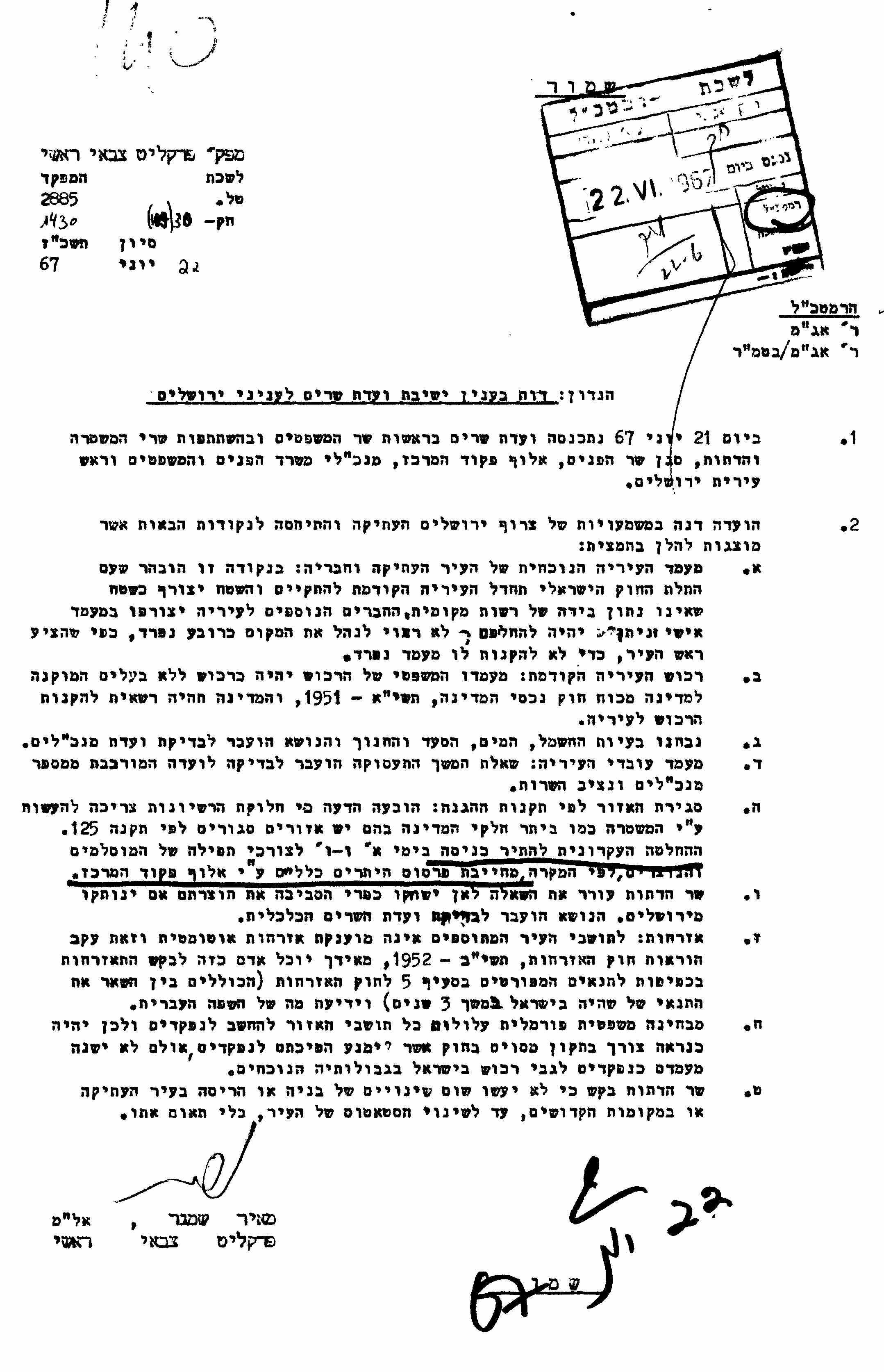

Settling the legal status of East Jerusalem residents

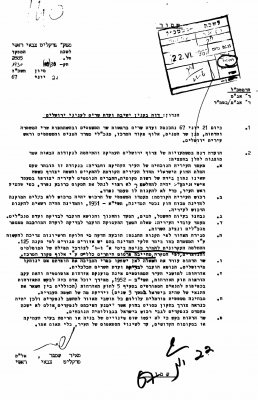

On August 30, 1967, the legal advisor for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Theodor Meron, wrote to the ministry’s executive director to caution that “legislative steps toward settling the status and legal rights of residents of East Jerusalem have yet to be made”. Meron addressed the issue ahead of a UN General Assembly session where the issue of Jerusalem was expected to be on the agenda.

Meron shared with the executive director his impression that even if staff at the Justice Ministry had begun preparations for legislation that would prevent property belonging to residents of East Jerusalem from being considered “absentee property”, in the absence of public or political pressure, work on this issue was progressing slowly. A similar issue requiring attention was the policy regarding anticipated claims from residents of East Jerusalem to have property that remained beyond the Green Line in 1948 returned to them. On this issue, Meron noted, rather than finding a statutory solution, the plan was to give the Guardian General, who was in charge of managing absentee property in Israel, and a dedicated special committee discretion to decide how to respond to claims.

Meron concluded by noting that the Ministry of Justice had not yet begun formulating a policy on the civil status of East Jerusalem residents. They were not Israeli citizens, but the law did allow them to apply for citizenship. In such cases, Meron noted, the law gives the minister of interior broad discretion.

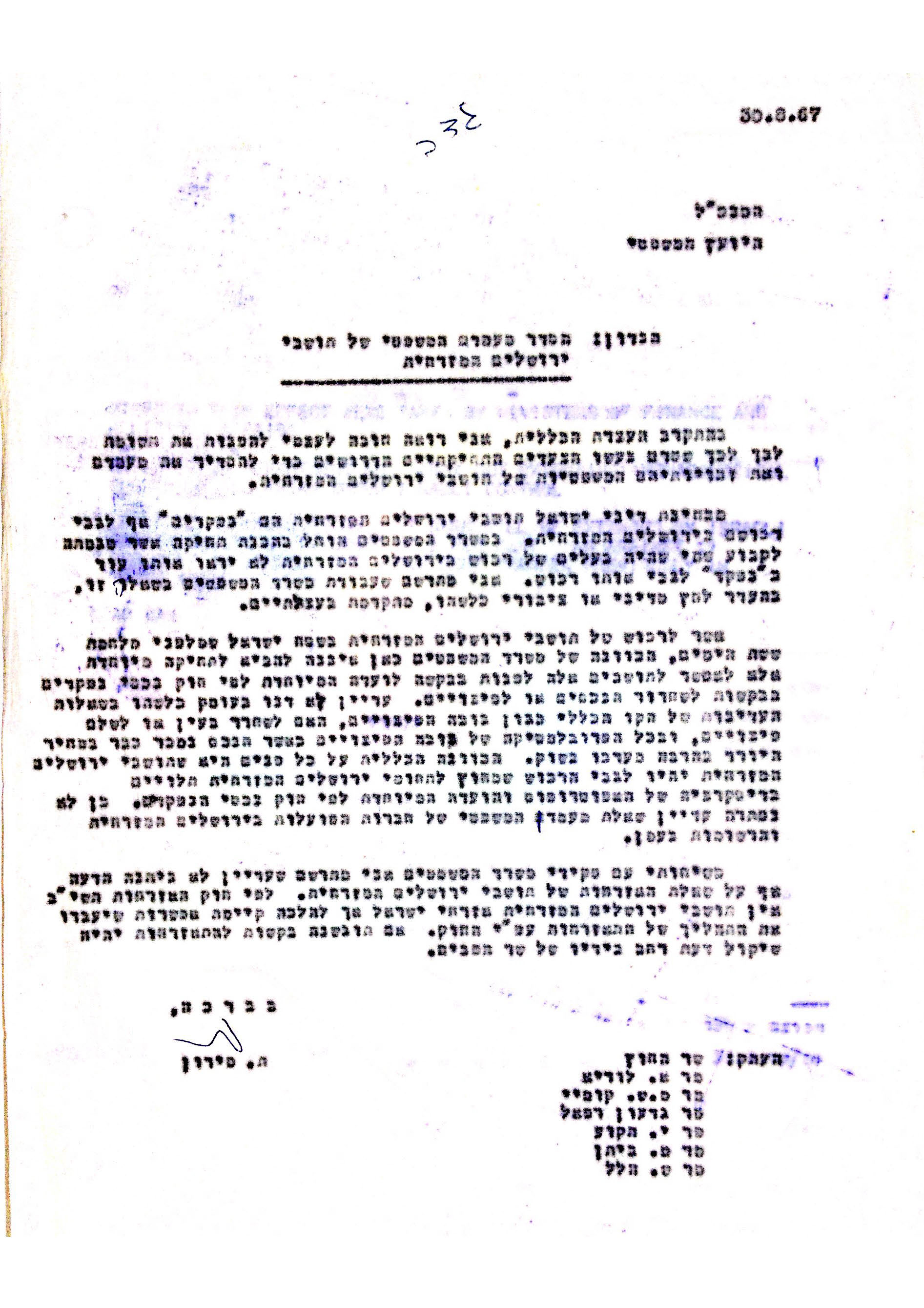

Citizenship of East Jerusalem residents

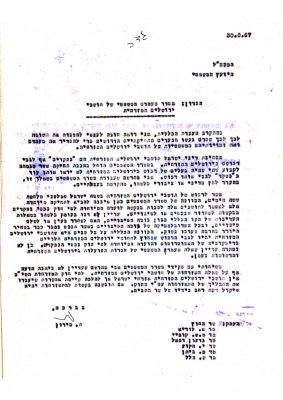

On March 14, 1968, Minister of Justice Yaakov Shimshon Shapira sent two letters to Prime Minister Levy Eshkol, classifying both as “Personal-Secret”.

One letter addressed the civil status of East Jerusalem residents. Minister Shapira explained the issue: According to the Citizenship Law, citizenship is automatically granted to persons eligible under the Law of Return (i.e. to Jews only), persons who were living in Israel in 1952, when the law was enacted, and persons at least one of whose parents was an Israeli citizen at the time of his or her birth. All other individuals are required to undergo naturalization in order to gain Israeli citizenship. The process has several threshold conditions, including, three years of living in Israel, some knowledge of the Hebrew language and renouncing the previous citizenship. The justice minister observed that the legal situation in fact precluded East Jerusalem residents from gaining Israeli citizenship, at that time, even if they wanted it. Given the uncertainty surrounding the issue and the anticipated public debate over the civil status of Palestinians in East Jerusalem, the minister suggested to the prime minister that the government discuss the matter and come up with a policy.

Residents of East Jerusalem and the Absentee Property Law

Another letter sent by the minister of justice to the prime minister that same day addressed property owned by East Jerusalem residents. Under Israeli law in place at the time, property belonging to East Jerusalem residents and located in East Jerusalem was considered absentee property; any property they owned in the western part of the city had been considered absentee property since 1948 and with respect to any property they owned inside the Green Line, East Jerusalem residents were considered “present absentees”.

In his letter, the minister noted that a committee he had appointed had found that property owned by East Jerusalem residents in west Jerusalem was worth over 320 million Israeli pounds (the equivalent of some 2.5 billion New Israeli Shekel today), and more should a decision be made to return property located in other parts of Israel. The minister noted that returning the property of East Jerusalem residents would compel the state to return property belonging to other “present absentees” in Israel. Minister Shapira suggested the prime minister consider the issue and decide whether to bring a “solid proposal” for discussion by the government.

East Jerusalem problems awaiting resolution

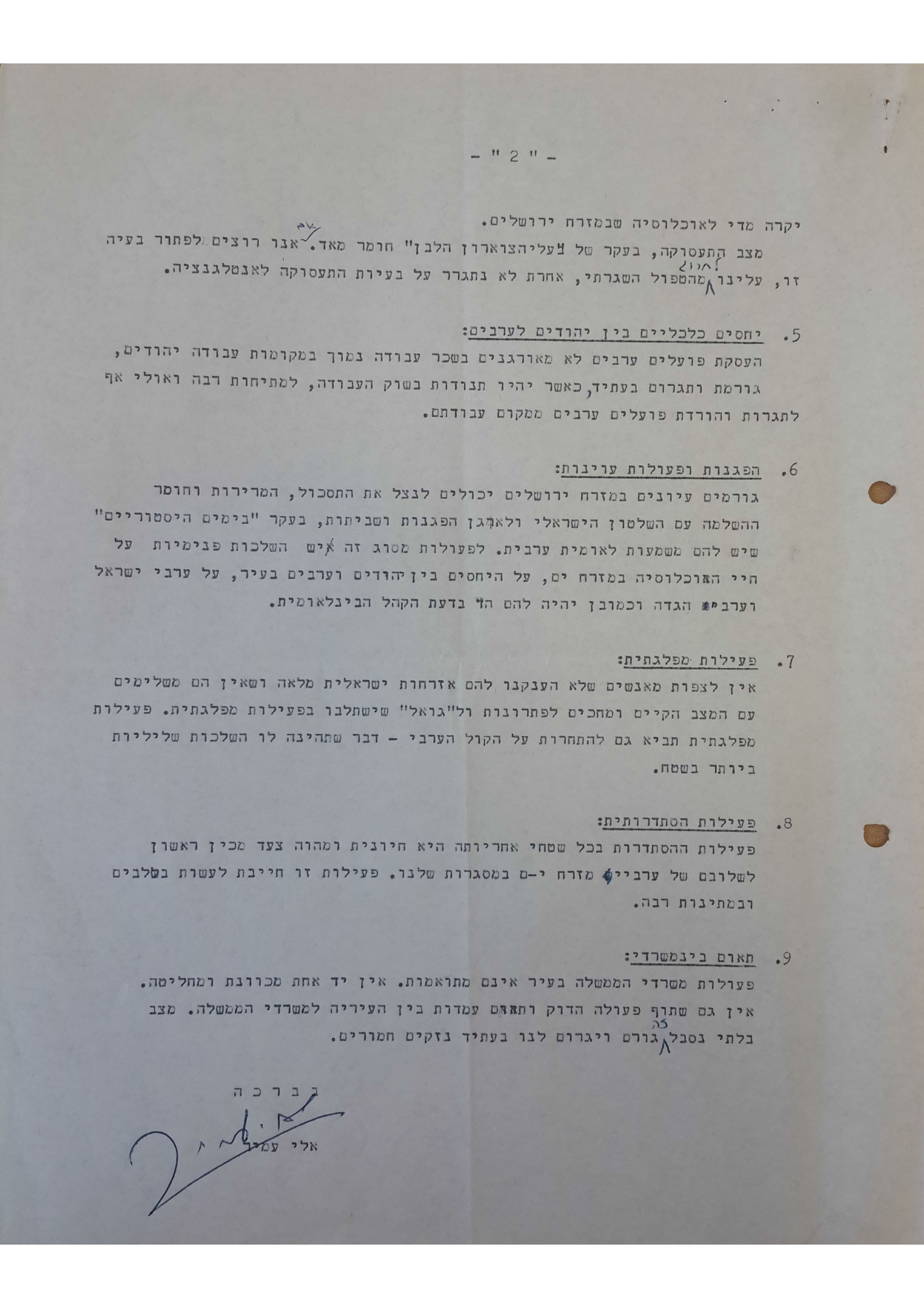

In the summer of 1968, Head of the Office of the Prime Minister’s Advisor on Arab Affairs, Eli Amir, wrote a short two-page memo containing a brief description of the major issues affecting East Jerusalem at the time, referring to them as “problems awaiting resolution”, about year into the annexation of the Old City of Jerusalem and 28 villages in its vicinity to the State of Israel.

The two-page memo written by Amir (who went on to become a renowned Israeli novelist, author of Scapegoat, The Dove Flyer and Yasmine), was submitted to Shmuel Toledano, the PMO’s Arab affairs advisor. In the memo, Amir gives very brief summaries of nine central issues, and stresses that the civil status of Arab residents of Jerusalem was “up in the air”, and with it, their political rights and the fate of the property that had been confiscated from them. He notes that the local Palestinian leadership had been undermined, and that East Jerusalem was in the grip of an economic and job crisis as a result of its sudden exposure to Israel’s economy.

Amir warns in the memo of the anticipated repercussions of the situation in East Jerusalem: tensions around jobs and pay, the possible exploitation of “frustration, bitterness and refusal to accept Israeli rule” by “hostile elements” and the alienation Palestinians from East Jerusalem feel toward Israeli political parties. The document describes the work of Israeli governmental authorities in Jerusalem as confused and uncoordinated, noting that this was and would continue to be the cause of “grave damage” to Israel.