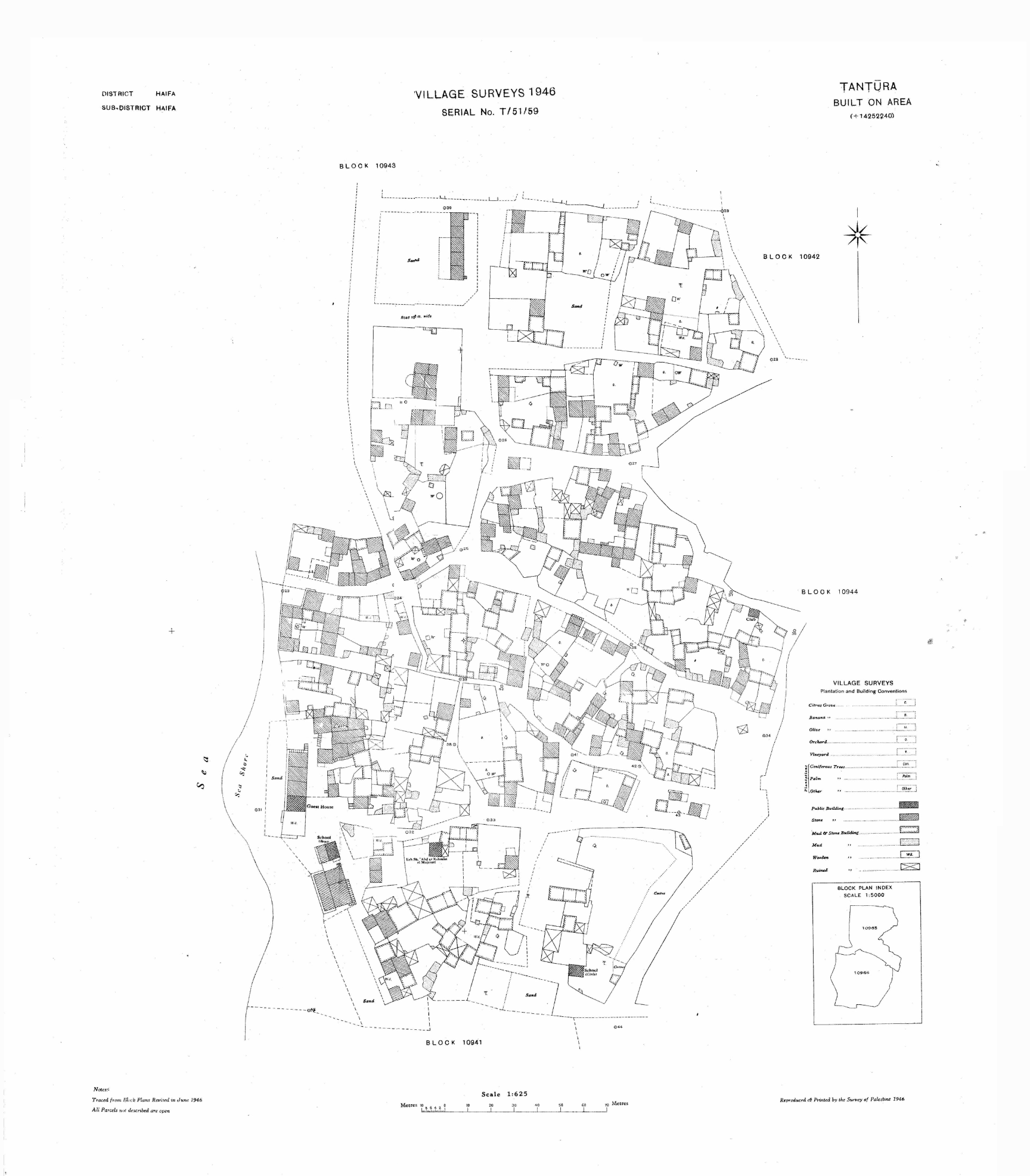

“Tantura,” a new documentary film by director Alon Schwartz revisits the story of the Palestinian village of Tantura (now Dor Beach, next to Kibbutz Nahsholim). The village, located on the southern Carmel shore, was conquered by the Alexandroni brigade’s 33rd battalion on the night between May 22 and 23, 1948. The film goes beyond the conquest of the village and the bitter fate of 1,500 of its residents, revisiting the firestorm that erupted in early 2000 after a master’s thesis for the University of Haifa examined whether Jewish fighters massacred detainees in Tantura. What do we know about what happened in Tantura? Why did a thesis paper cause such an uproar?

In March 1998, a University of Haifa student by the name of Theodore Katz (then in his fifties) submitted a masters’ thesis to the department of Middle Eastern History, entitled,“The Exodus of the Arabs from the Villages at the Foot of Southern Mount Carmel in 1948.” The thesis received a grade of 97 out of 100 and was deposited in the university library. Katz planned to pursue a Ph.D., but his plans went awry when in January 2000, journalist Amir Gilat borrowed the thesis from the library and published a story about it in Maariv daily newspaper, entitled “The Tantura Massacre.” The story ignited a firestorm. The Alexandroni Brigade Veterans’ Association and other former soldiers filed a libel suit against Katz, and the university. Two years after approving the thesis, a university committee was set up to reexamine the thesis and ultimately disqualified it.

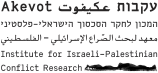

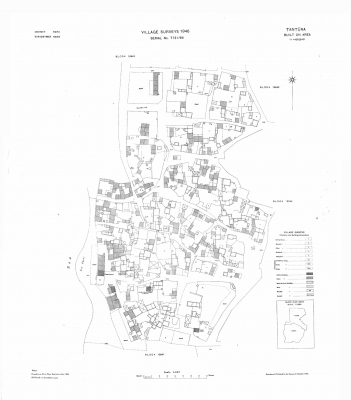

The fact that the residents of Tantura were expelled from their village is undisputed. In early April 1948, some six weeks before the village was conquered, the General Staff/Operations Directorate agreed that a “plan for settlement” should be drafted and Jewish residents should be moved to live in the village. Such a plan was ultimately implemented. At the time, decision-makers knew Tantura was a populous Palestinian village and that securing Jewish settlement there would necessarily entail a mass expulsion.

Still the question remains whether the conquest of the village, a battle during which 14 Jewish fighters were killed, was followed by the murder of Arab fighters or residents who were held at the site. Listening to the recordings of testimonies given to Katz by soldiers who had taken part in the Tantura battle and watching the new testimonies included in Schwarz’s film indicate that individuals held by Jewish fighters were in fact murdered in Tantura. Speaking now, one of the former soldiers talks about Arabs being shot by a soldier he describes as a “savage” with a submachine gun. “They silenced it,” he adds, “It mustn’t be told; it could cause a whole scandal. I don’t want to talk about it, but it happened. What can you do? It happened,” he tells Schwartz. He is not the only combatant attesting to the violence that pervaded the village, and his descriptions are corroborated by several testimonies.

Another combatant recounts how one soldier approached a group of 15-20 detainees “and killed them all.” The combatant says he was appalled, and he spoke to his fellow soldiers to try to find out what was going on. “You have no idea how many [of us] those guys have killed,” he was told. Today, the former soldier stresses he was only interested in knowing why unarmed individuals were executed, “and nothing more.”

Another soldier who fought in the village speaks of an officer “who in later years was a big man in the Defense Ministry. With his pistol, he killed one Arab after another.” He says the officer killed the men because they would not disclose where they had hidden weapons in the village.

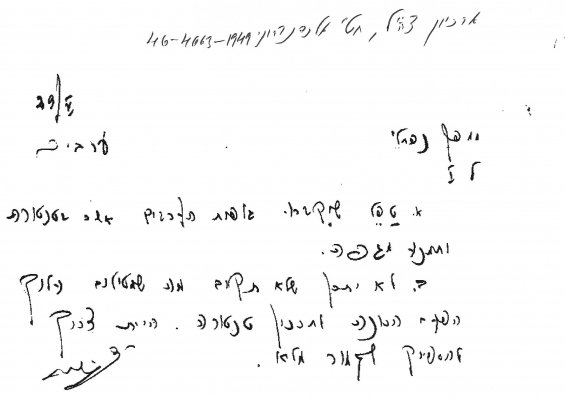

The interviewees’ reticence and the difficulty they have talking about Tantura is apparent when listening to the many testimonies. Twenty years ago, Shlomo Ambar, who later rose to the rank of brigadier general and served as the head of Civil Defense, the predecessor of today’s Home Front Command, told Katz: “What do you want? For me to be a delicate soul and speak poetry? I moved aside. That’s all. Enough.” Speaking in the film, Ambar made it clear that the events in the village had not been to his liking, “but because I didn’t speak out then, there is no reason for me to talk about it today.” Another combat soldier told Katz about another incident: “It’s not nice to say this. They put them into a barrel and shot them in the barrel. I remember the blood in the barrel.” This is immediately followed by Ambar saying: “No, don’t write that.”

According to an article by the historian Benny Morris from 2004 Amatzia Amrami, one of the Alexandroni soldiers at the forefront of the campaign against Katz, wrote in an affidavit submitted to court that he was distraught over Katz’ allegations. There is no reason to doubt this, but listening to the testimony Amrami himself gave Katz is rather unsettling. “I won’t tell you what happened in Tantura,” he says, noting he did not personally witness anything, but heard rumors that, “a good number of Arabs were liquidated over there,” as revenge for the death of Jewish soldiers in the battle for Arab Kfar Sava, which took place a few days earlier. Like other interviewees, Amrami chooses his words carefully: “I wouldn’t say massacre. There was a little more. They killed a little more. It didn’t happen in many places. It happened here and there. What can I tell you? I’m sorry. I put too much emphasis on this. I don’t know what to tell you. Erase it (the recording).”

Over the past 20 years, the debate about this affair touched mainly on the legal and academic aspects rather than the bloody events of the day, in large part because Katz himself signed a letter of apology after a single court hearing, confirming there was no massacre and stating his thesis was flawed. The fact that just hours later he retracted this and that Avigdor Feldman, his lead lawyer and the one who represented him in court, was not present at the nighttime meeting where Katz was pressured to recant was forgotten. The apology meant the allegations Katz made were never seriously considered, and the affair was never comprehensively investigated.

The number of casualties found in Tantura after the May 23 conquest is unclear, as testimonies differ running the gamut from less than ten to 250. The historians who addressed the episode – from Yoav Gelber to Benny Morris and Ilan Pappé – reached different and contradictory conclusions. Gelber asserted that a few dozen Arabs had been killed in the battle itself, but that a massacre had not occurred. Morris, for his part, thought that it was impossible to determine unequivocally what happened, but wrote that after reading several of the testimonies and interviewing some of the Alexandroni veterans, he “came away with a deep sense of unease.” Pappé, who engaged in a highly publicized debate with Gelber over Katz’s thesis, determined that a massacre had been perpetrated in Tantura.

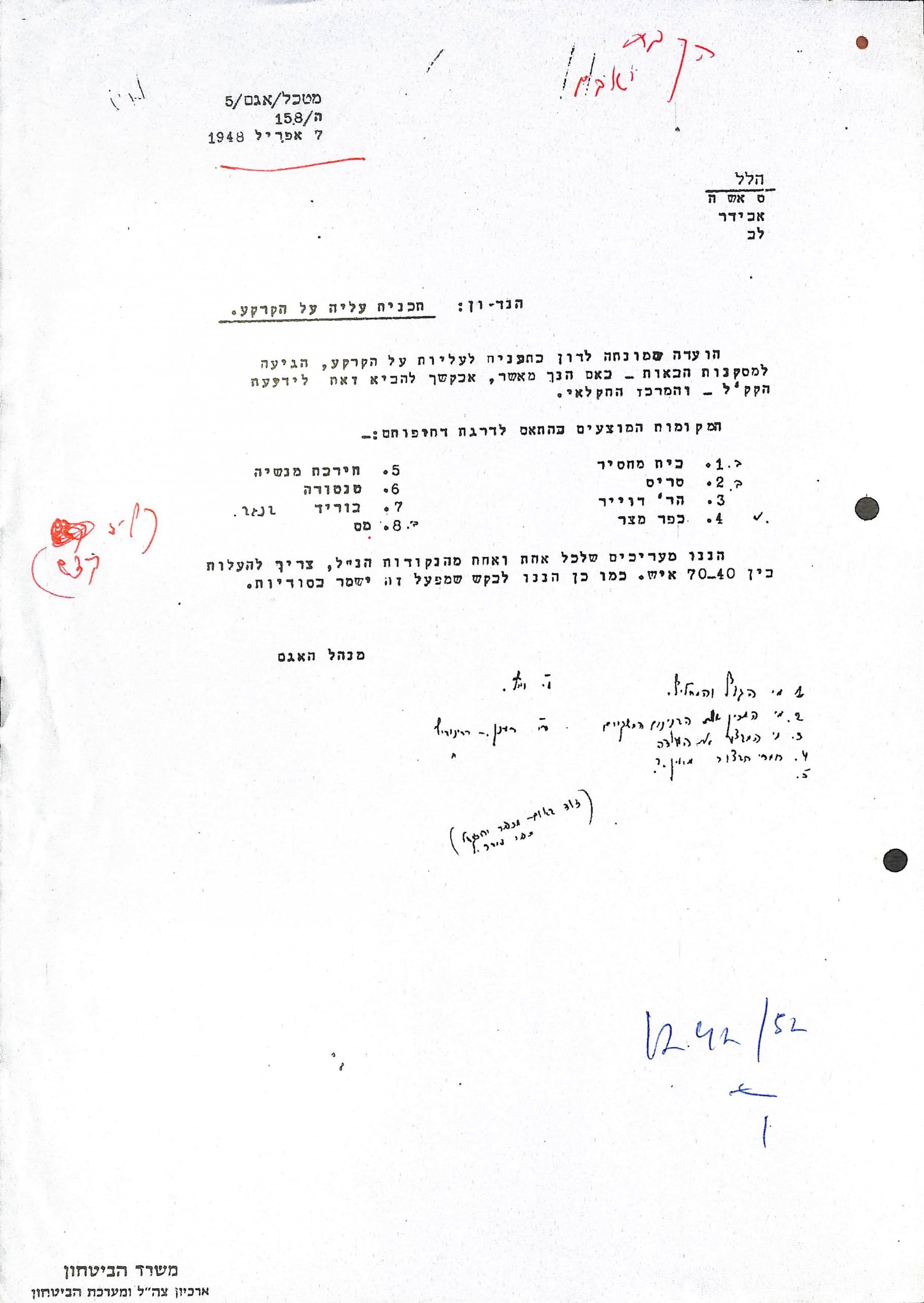

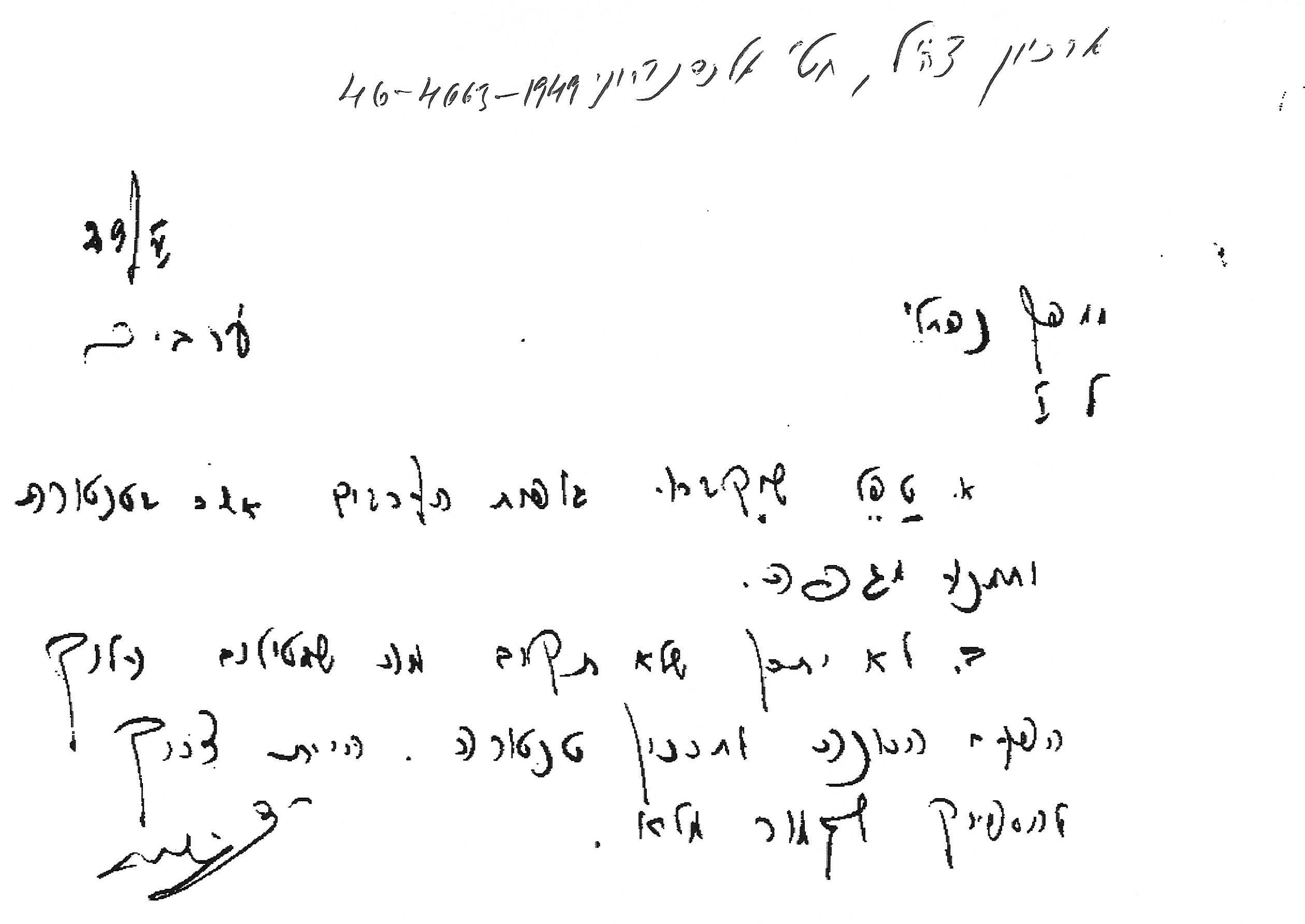

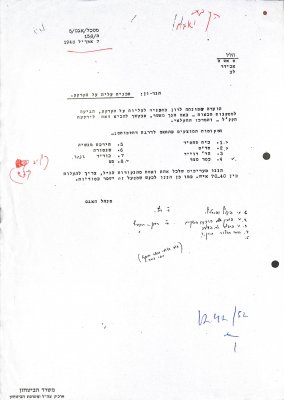

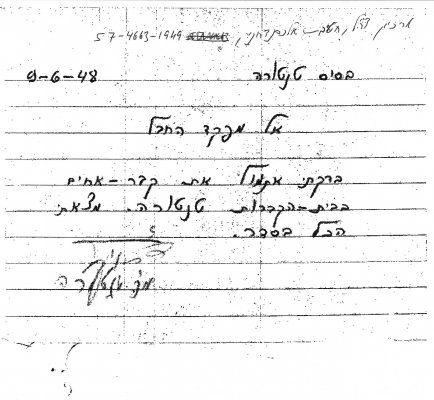

Archival records that are open for public access clearly indicate no one counted the bodies or kept a record. As a matter of fact, it took quite some time to collect the dead and bury them in a mass grave. In late May, a week after the conquest, one of the commanders who was posted at the site was reprimanded for not having dealt properly with the burial of the Arabs’ bodies. “It is unacceptable,” he was told, “that you fail to carry out what you were tasked with […] You should have fully completed it.” On June 9, the base commander reported back: “Yesterday I checked the mass grave in Tantura cemetery. Found everything in order.” However, a reporter with the Davar newspaper two days later reported of “the stench of rot” in the village and of “comrades finding more bodies of dead Arabs stuck among the bushes and thorns.”

The Tantura affair exemplifies the difficulty many soldiers who participated in the 1948 war had speaking their experience, particularly those shedding light on some events of reprehensible conduct: looting, violence against Arabs, expulsion and – in some cases acts of murder. To listen to the soldiers’ testimonies today, while considering the uniform stand they demonstrated when they sued Katz, is to grasp the potency of the conspiracy of silence and the consensus that there are things better left unsaid. Hopefully, from the perspective of years, such subjects will be more readily addressed by Jewish Israelis.

A feature by Akevot Institute researcher Adam Raz about the Tantura affair was published in Haaretz daily newspaper on January 21, 2022.