The Kafr Qasim Massacre: Document Library is an invaluable tool for educating our communities and ourselves, information sharing, and facilitating discussion around the massacre and its impact in the public sphere. The website contains thousands of pages of digitized documents, capitalizing on the primary sources about the massacre revealed to date, and background on the incident and the famous trial that followed. It also illuminates deliberate efforts to conceal the event and erase it from public memory.

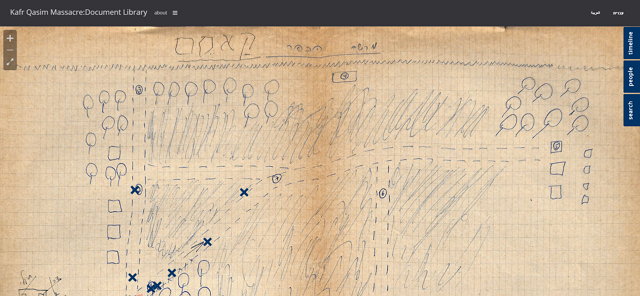

On October 29, 1956, the first day of the second Arab-Israeli war (known in Israel as the Sinai or Kadesh Operation and internationally as the Suez Crisis), the daily curfew imposed on the village of Kafr Qasim was pushed up from 10:00 PM to 5:00 PM. Laborers who were working outside the village at the time were not aware of the change. From 5:00 PM to 6:00 PM, 47 Arab citizens – children, women, and men who were returning home, were murdered in the village. Two more people were murdered in the nearby villages of Taybeh and Tira. Including the unborn daughter of Fatma Sarsur, who was eight months pregnant when she was murdered, as well as ‘Abdallah ‘Issa, an elderly man whose heart stopped beating several hours after the massacre, the massacre took 51 lives. The massacre, and its aftermath – from the secrecy, obfuscation, politics and whitewashing to the trials and the public reaction, became a seminal event in Israel’s history in general, and in the history of its Arab public in particular.

The website, that went online on the massacre’s 63rd anniversary, reflects Akevot’s mission to make primary sources regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict accessible and Adam’s belief that the public should be able to critically evaluate the sources he used to write his book. The documents in this digital library include the full transcripts of the military court hearings, testimonies given to criminal investigators and various commissions of inquiry, evidence submitted to court, transcripts of government meetings, and more. While the documents are largely in Hebrew, descriptions and summaries are also available in English and Arabic.