Locating absentee property, handling collaborators and identifying local millionaires: an internal report summarizes the first year of the ILA East Jerusalem branch.

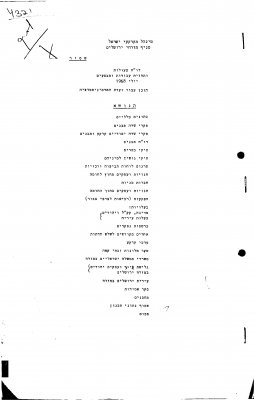

About a year after it began its operations, the East Jerusalem Branch of the Israel Land Administration (ILA, which has since been renamed the Israel Land Authority), prepared a report about its activities, likely ahead of an internal discussion regarding its future. The branch manager described the activities conducted by his office as work that cannot be done “in the ordinary manner” and requires “prompt and categorical responses”, meaning that branch officials need far-reaching powers and the ability to take action “without the ordinary bureaucracy and administrative processes”.

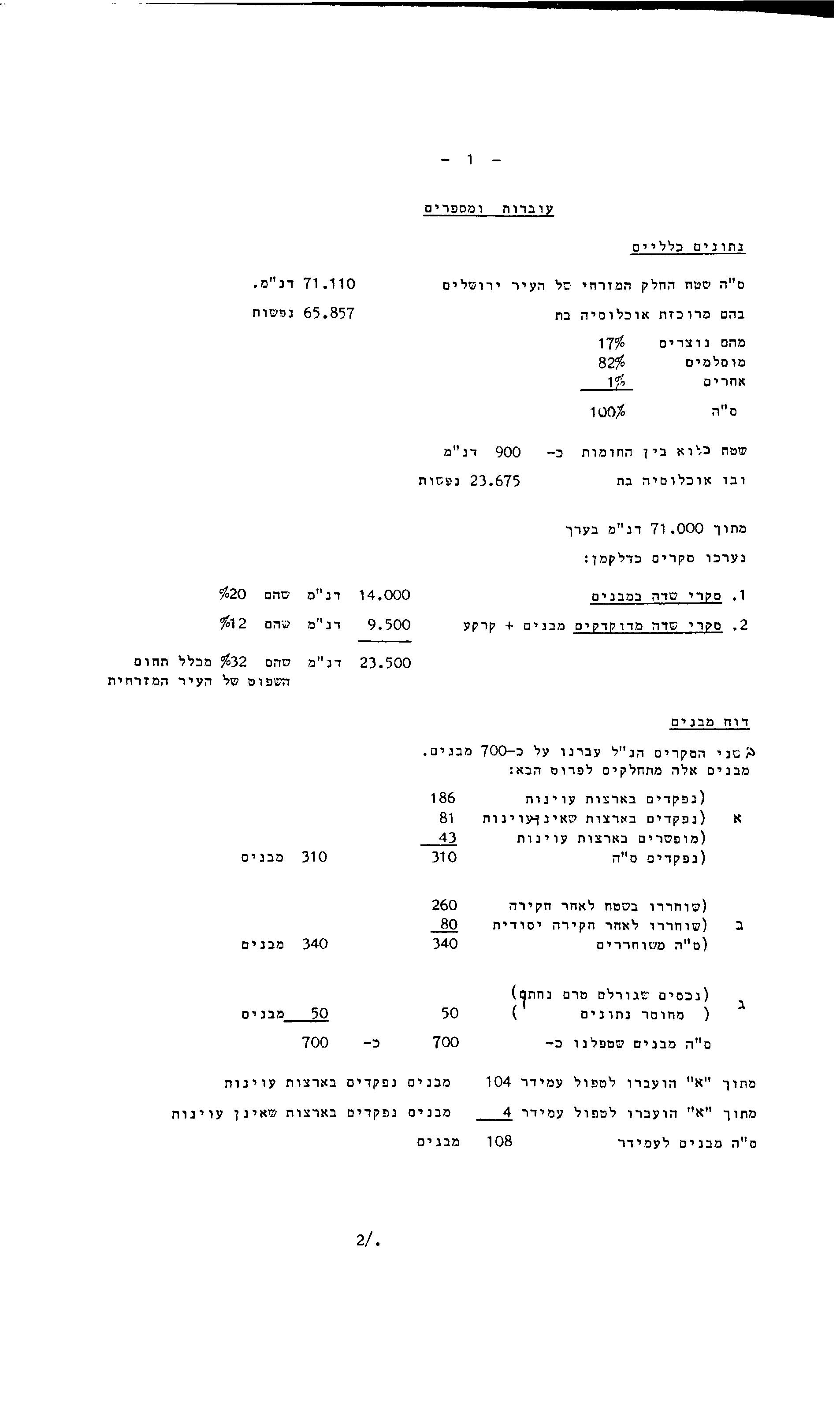

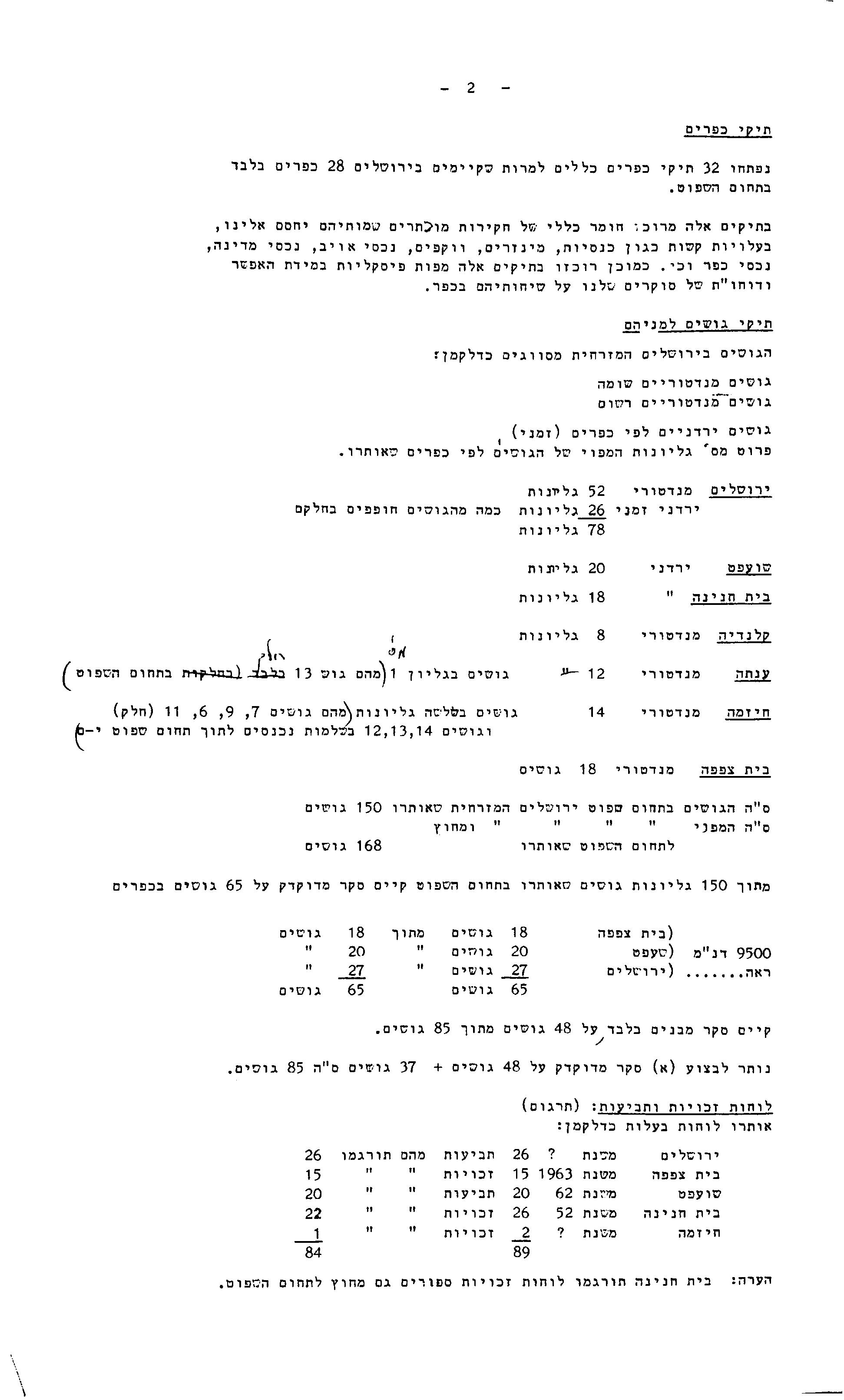

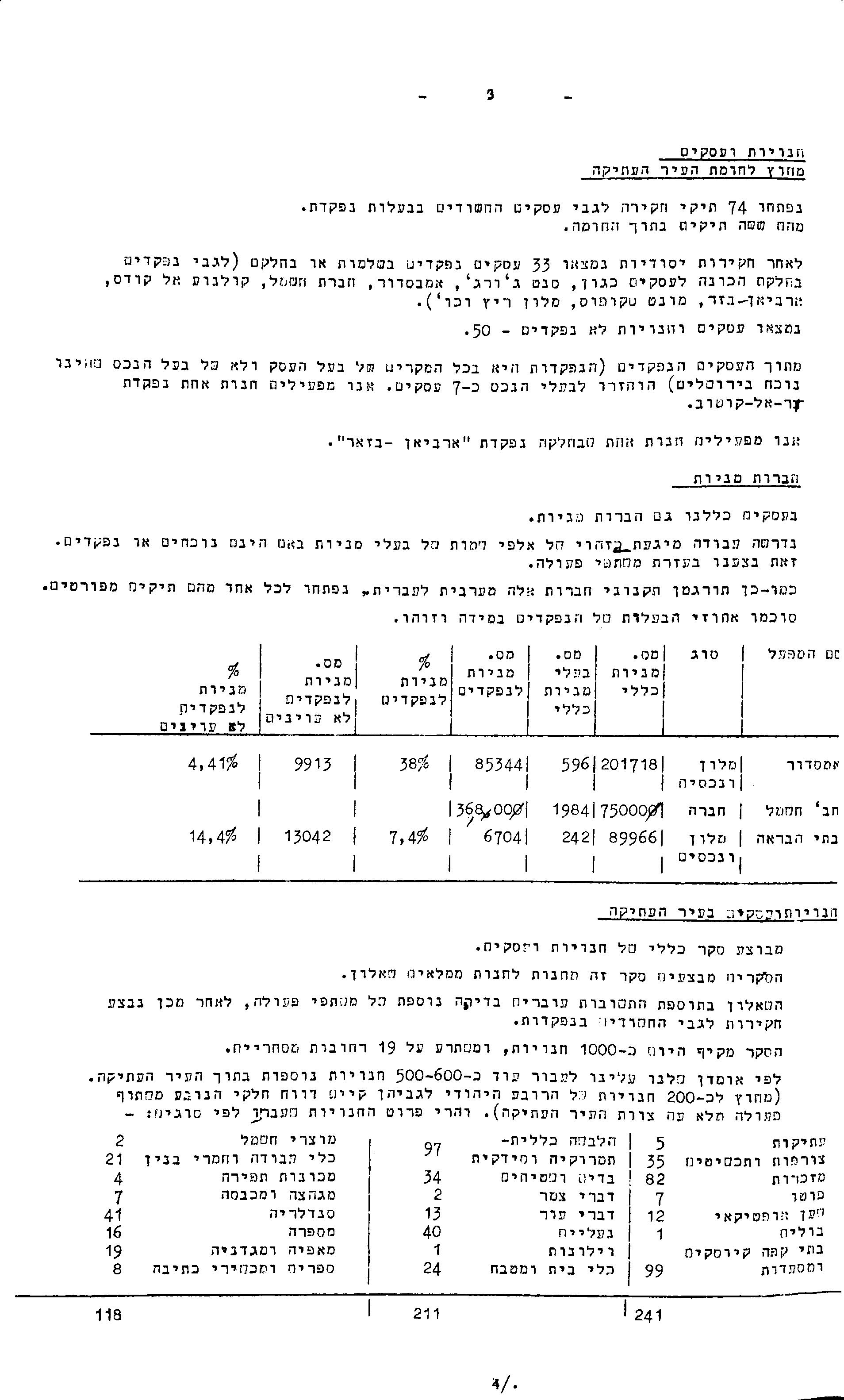

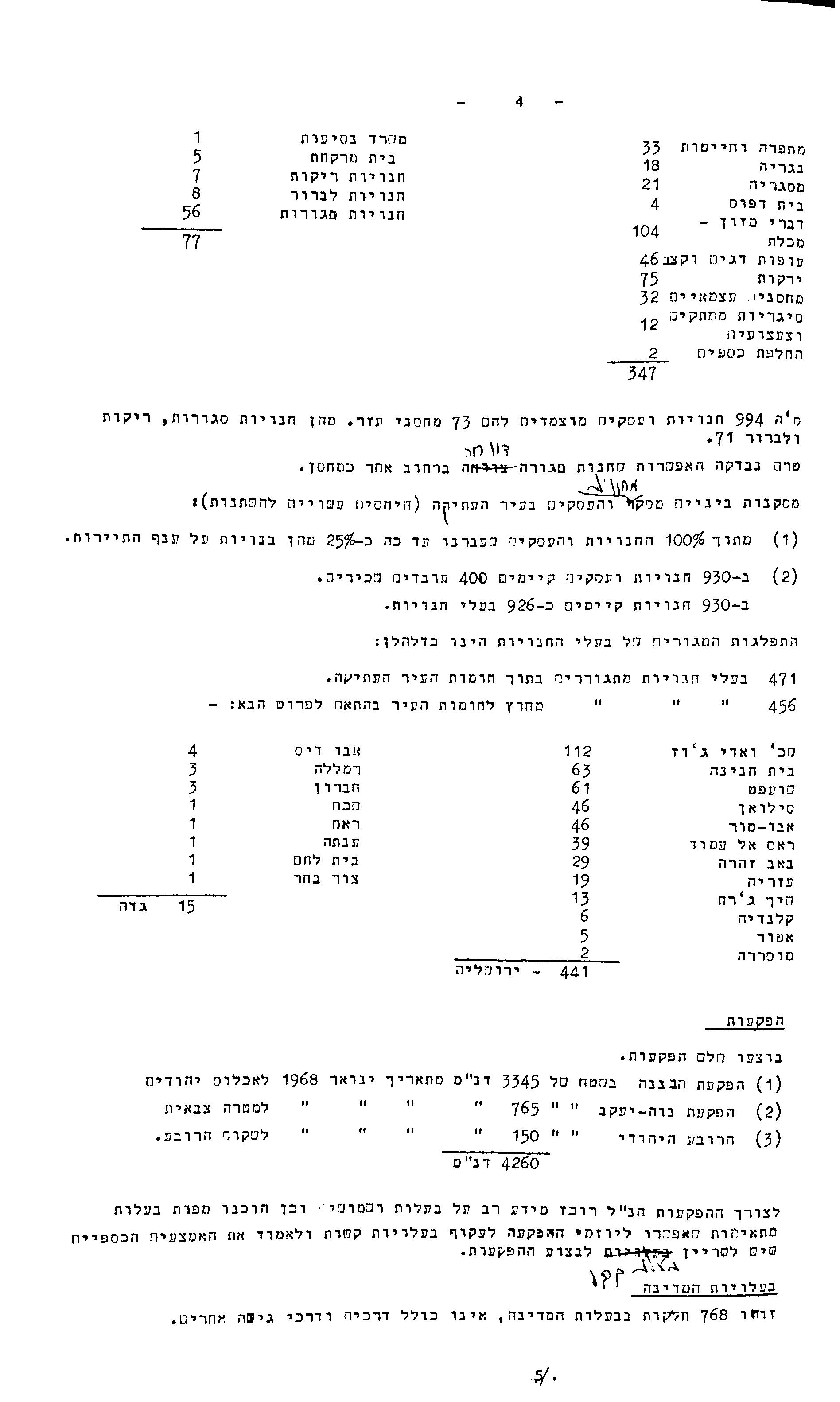

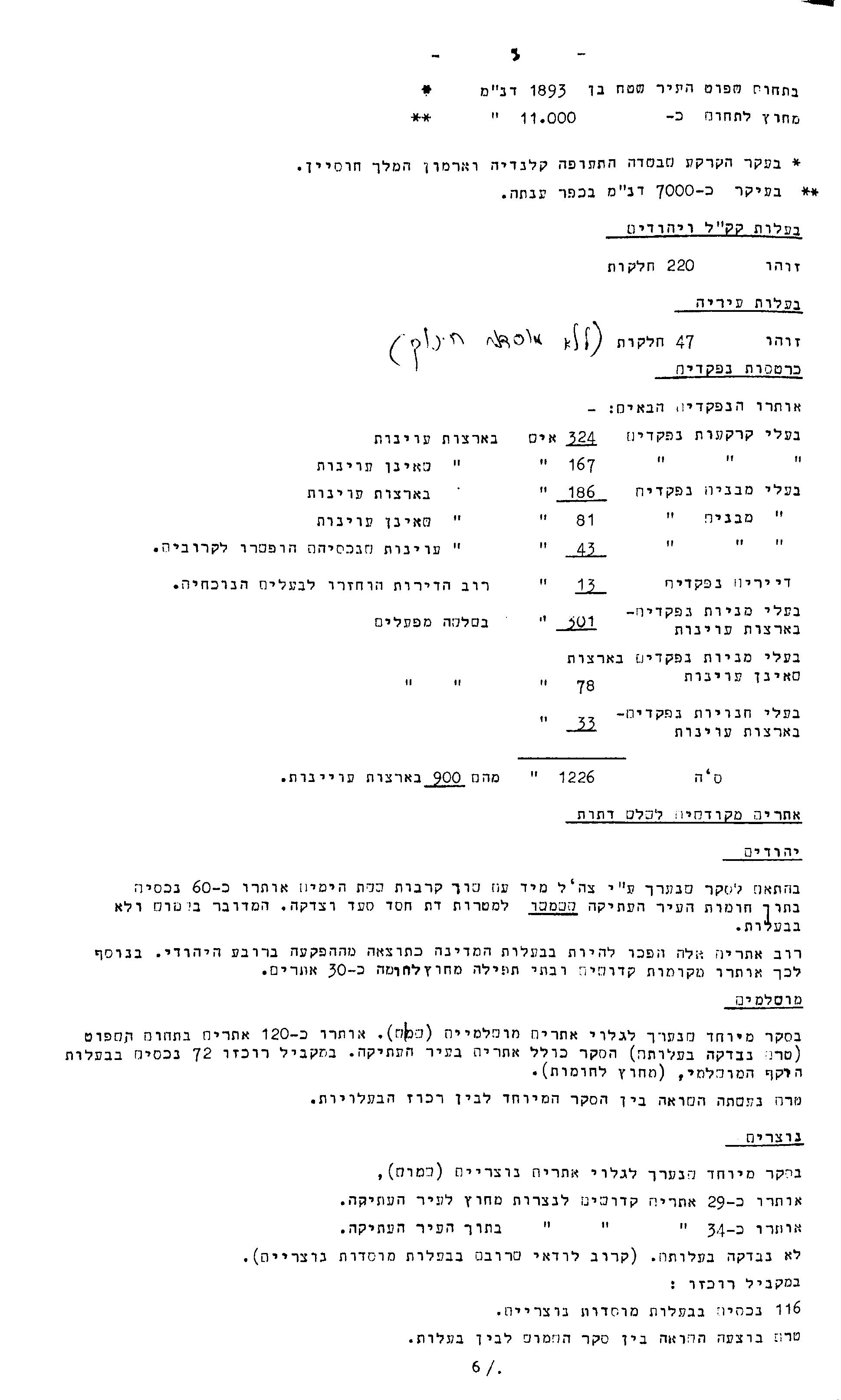

Large parts of the report reflect the work the ILA devoted to identifying and mapping out absentee property, that is, property belonging to Palestinians who left the city during and after the war. By the time the report was written, the branch had surveyed some 32% of East Jerusalem. Buildings, lots and businesses were carefully mapped in order to locate properties whose owners were considered “absentees”, and could therefore be transferred to the Israeli authorities (for a fact sheet on Israeli policy on Absentee property in Jerusalem, see NRC’s The Absentee Property Law and its Application to East Jerusalem). The authors of the report noted that “painstaking work” had been carried out, using Palestinian collaborators, to find out who among the thousands of shareholders in East Jerusalem public companies were considered “absentees”. The information was recorded in a separate absentee card catalog prepared at the branch. Records were also kept of the movable property the authorities had seized. Its value was estimated at 150,000 to 200,000 Israeli pounds (US$ 309,000-418,000), and it was earmarked for transfer to various institutions and for internal or closed bids.

The report also presents numerous findings regarding the state of East Jerusalem’ economy and demographics in this area in the early months after its creation and annexation to Israel. For instance, a “wealth survey” the ILA conducted identified about 200 millionaires and “semi-millionaires” living in East Jerusalem. Their personal information was recorded, together with details about their property, and their geographic location and religion were charted as well.

The report also contains information about land the State of Israel expropriated in East Jerusalem, and on Israeli government institutes opened in East Jerusalem. Something described in the report as a “trickle of Jewish persons, apartments and businesses flowing into East Jerusalem” included, at the time – July 1968 – six banks, two public relations offices, a law office, medical and welfare institutions and a coffee shop.

In the final section, the branch managers concludes with a long list of tasks still left for the ILA in East Jerusalem: beginning with surveying the borders of the city in order to devise policies for the seam zones, continuing with finding out “the true reason for the reluctance to sell land and lease homes to Jews, and findings ways around the objective obstacles”, and ending with resolving the question of whether the owner of 300 commercial refrigerators could be considered an “absentee company”.