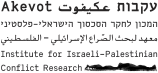

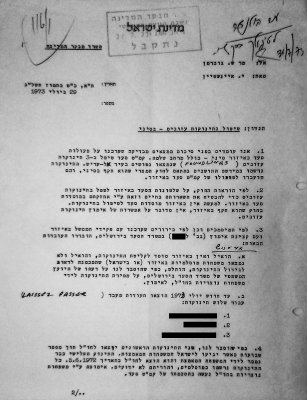

1973 Correspondence from the State Comptroller’s Office reveals Israeli welfare authorities illegally sent Muslim babies abandoned in the Sinai Peninsula for adoption by Christian families abroad.

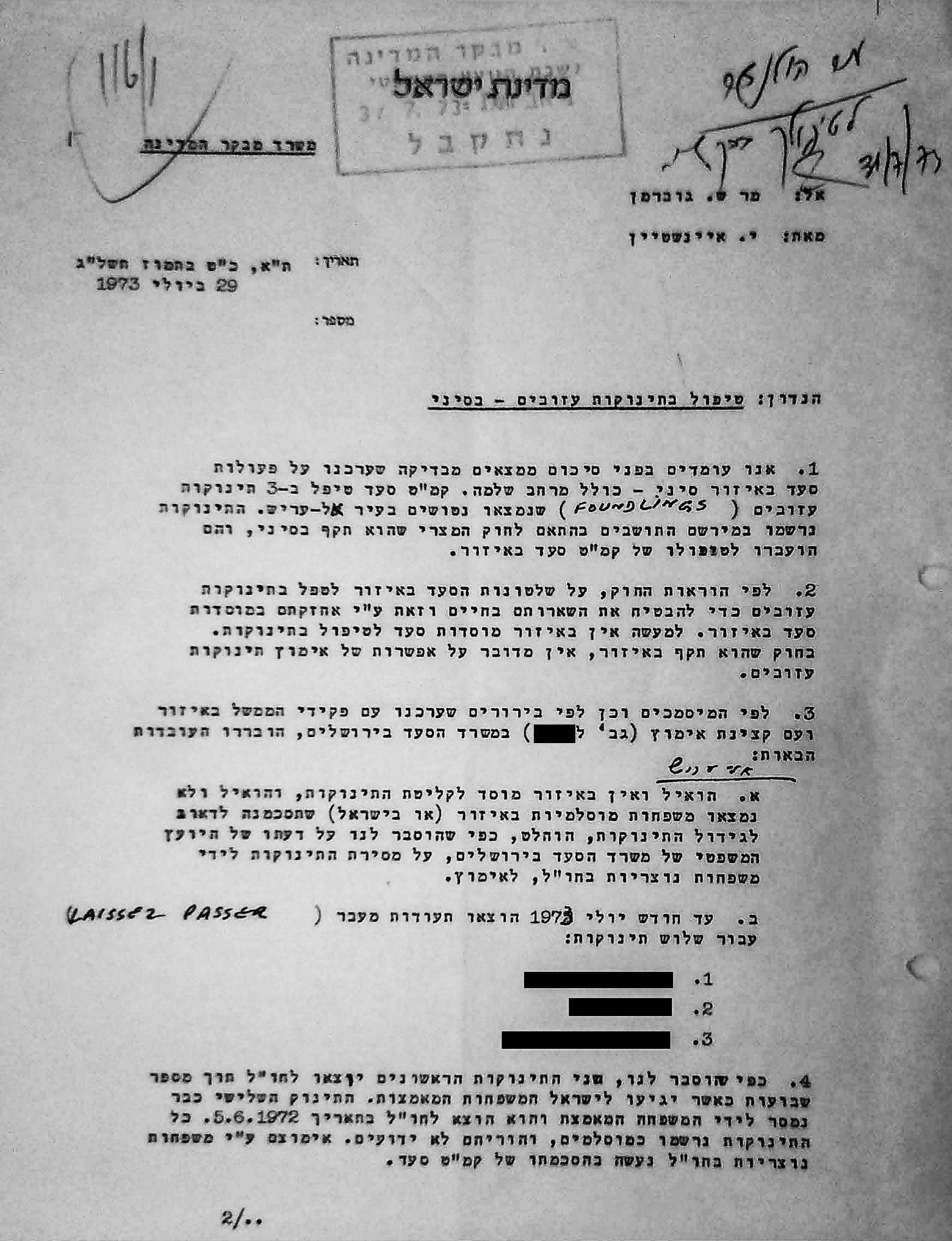

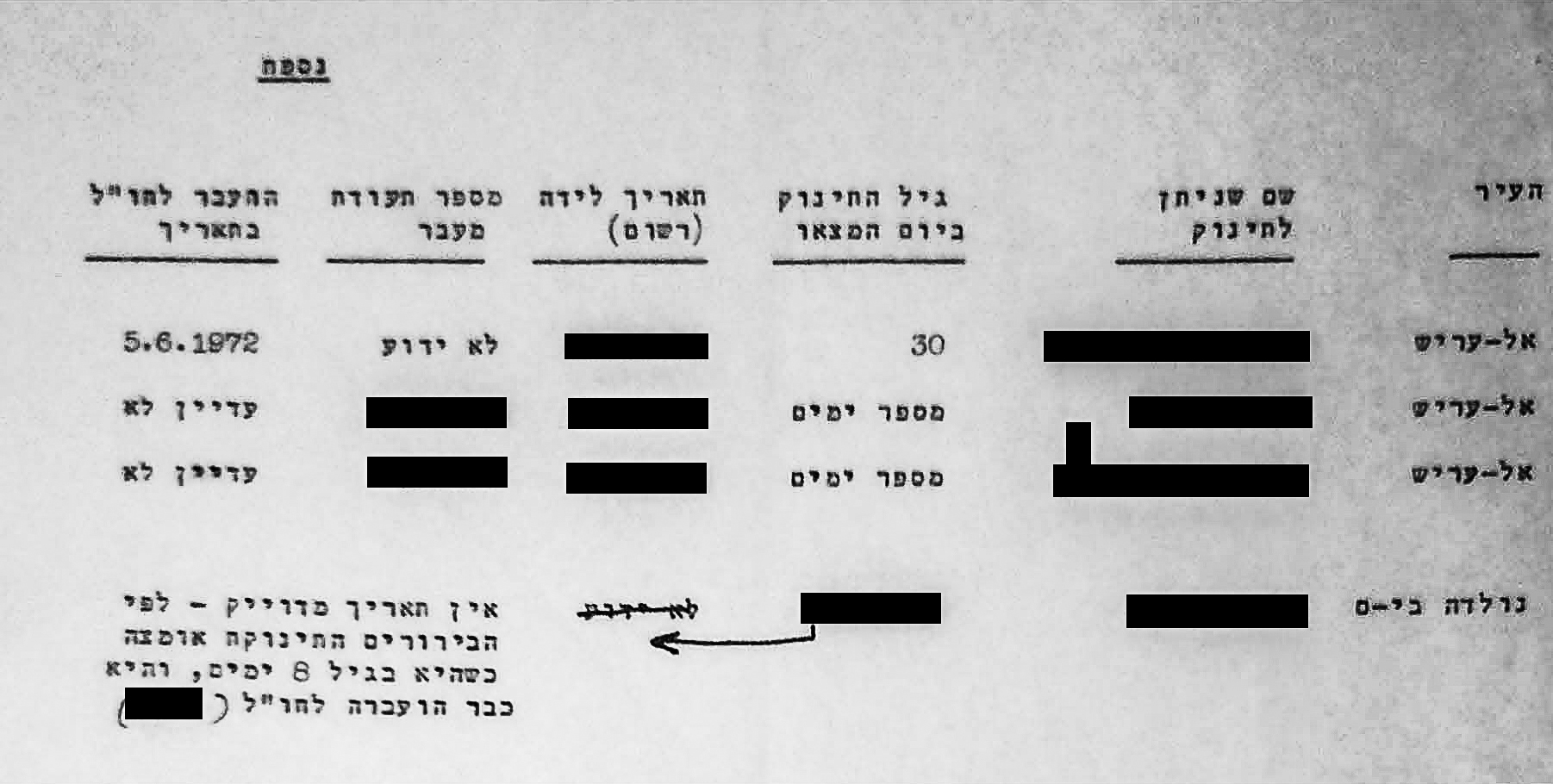

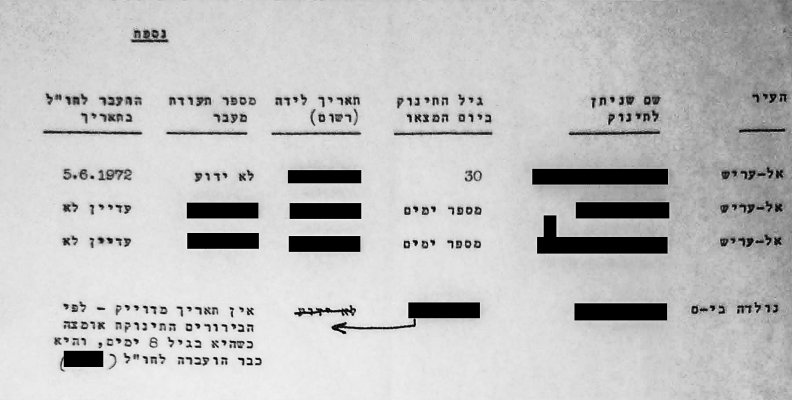

In the early 1970s, three abandoned babies were found in the town of al-Arish, in the Sinai Peninsula. They were turned over to the care of the Israeli military government authorities. When it turned out there were no facilities to care for abandoned babies in the Sinai Peninsula, and no Muslim families in the Sinai or in Israel agreed to take them in, the welfare officer of the military government and the Israeli Ministry of Welfare decided to send the babies for adoption by Christian families abroad. The case was uncovered during inquiries made by the State Comptroller’s Office. The office also uncovered a separate case, in which a Muslim baby from the Sinai who was born out of wedlock, was also adopted and taken to Europe by a Christian family. In this case, written consent was given by the mother.

By the time the affair was exposed, two of the babies had already been sent abroad and given over to their adoptive families. The other two were due to be given to their families within a short time. The staff at the State Comptroller’s Office were not satisfied with the opinion of the legal advisor to the Ministry of Welfare, which sanctioned the babies’ adoption, and they asked for the opinion of their own legal department.

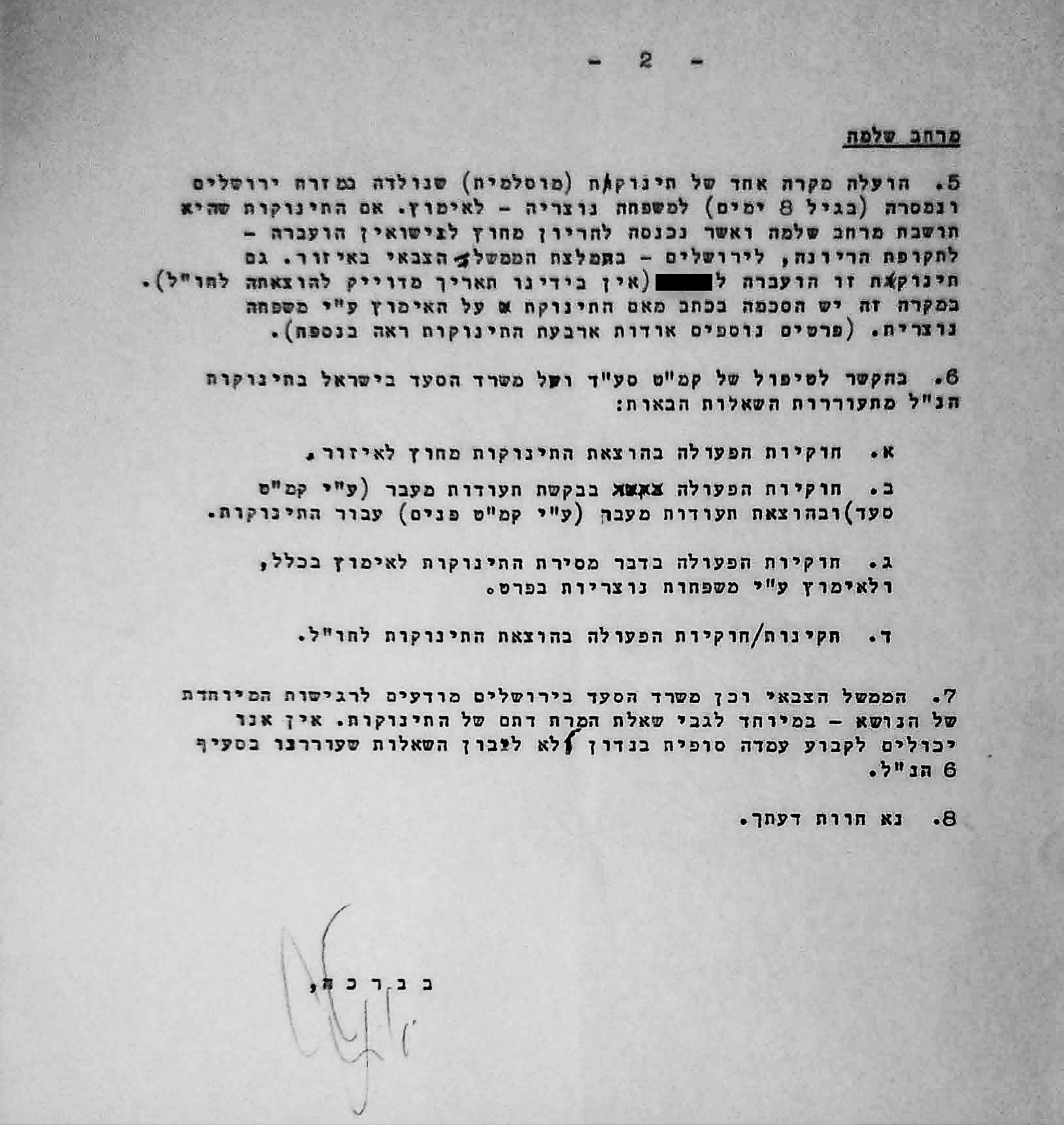

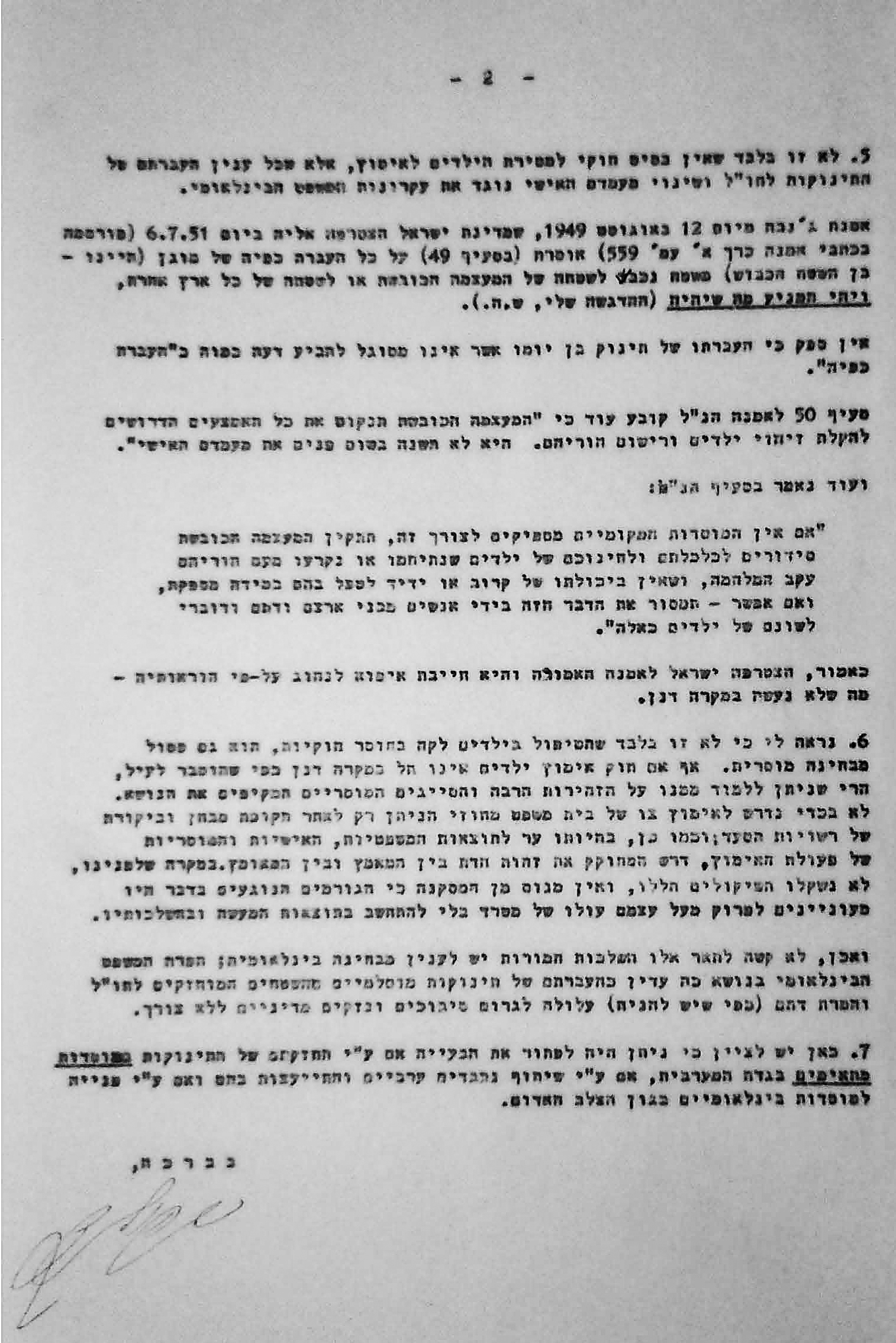

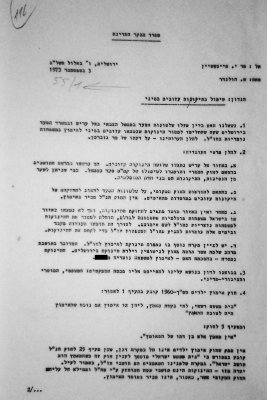

Their request was answered by Shmuel Hollander, then Deputy Legal Advisor to the State Comptroller’s Office (and subsequently the Civil Service Commissioner and Government Secretary). Hollander asserted in his opinion unequivocally that “not only has the handling of the children been tainted by illegality, it is also morally unacceptable”.

Hollander noted that handing the Muslim babies over to Christian families in Europe was a violation of both the local law in the Sinai – which does not acknowledge adoption – and also of international law. Hollander listed the provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention that had been violated. These include the prohibition on transferring civilians outside the occupied territory (Art. 49 of the Convention), the prohibition on changing children’s personal status and the provision that children who have been orphaned or separated from their parents should be cared for by “persons of their own nationality, language and religion” (Art. 50).

Hollander stated that though Israeli adoption law did not apply in the occupied territories, its provisions are indicative of the great care that must be employed when children are sent for adoption. Hollander further determined that sending Muslim children from the Sinai for adoption by Christian families abroad and the children’s expected conversion could cause “unnecessary political damage and complications”, adding, “in the case at hand […] there is no denying the conclusion that the officials involved were interested in unburdening themselves of a nuisance without considering the ramifications and results of the act”. The deputy legal advisor wrote that the correct course of action would have been to contact the local leadership, welfare institutions in the West Bank, or the International Committee of the Red Cross.