When the Latrun area was occupied in June 1967, residents of the Palestinian villages of Amwas, Beit Nuba, and Yalo were expelled, and their communities were razed to the ground. Members of Kibbutz Nachshon, the nearest Jewish community, witnessed the destruction in real-time. In internal discussions immediately after the war, they debated what to do with the property left behind by their neighbors, the crops nearly ready for harvesting in the fields, and the fertile land that now lay deserted.

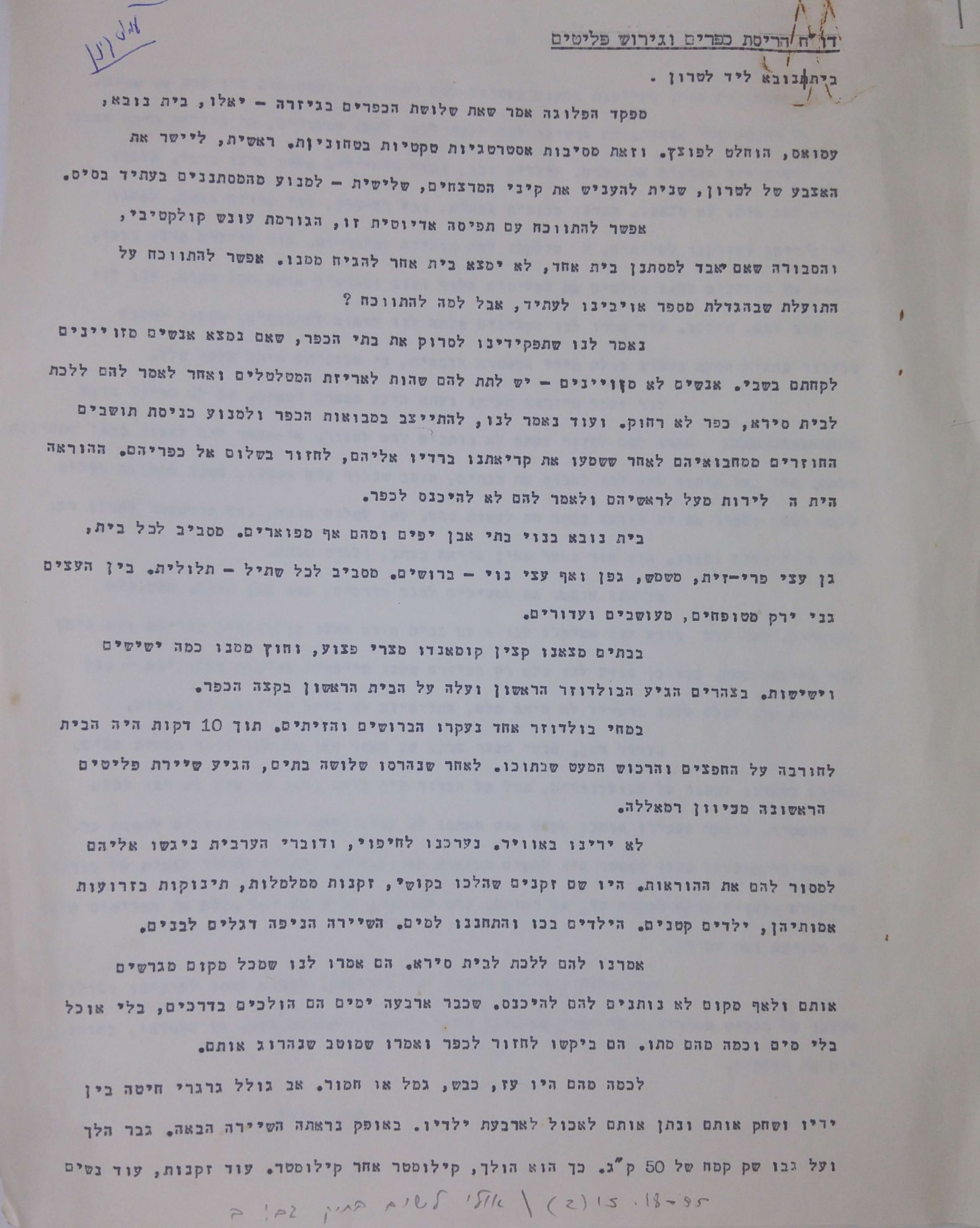

Three Palestinian villages in the Latrun area were depopulated after the Israeli army conquered them in the 1967 war. Residents of Amwas, Beit Nuba, and Yalo, numbering about 8,000 in total, were expelled towards Ramallah, and in the final days of the war, bulldozers were brought in to raze the village homes. The nearby village of Deir Ayub was depopulated back in 1948. In 1971, the moshav community of Mevo Horon was built on the site once occupied by Beit Nuba, and five years later, Canada Park was built on the lands of Amwas and Yalo. The project was led by the JNF with financial backing from Canada’s Jewish community. Over the years, there was some controversy over why the villages had been destroyed and who gave the orders, but the fact that the residents of the three villages were forced out of their homes seems to be beyond dispute.

On the second day of the war, the commander of the Fourth Regional Brigade, Moshe Yotvat, ordered the seizure of the Latrun enclave. The Latrun police building was taken by Israeli forces within two hours, and within several more, the entire Ayalon Valley was in the hands of the IDF, which encountered no real resistance. After the villages were conquered, residents were told to come out and gather in an open space. At 9:00 A.M., they were told to head to Ramallah. The Combat Sheet (a brief on the operation circulated to soldiers by the unit commander, usually using impassioned language to boost their fighting spirit) issued by the Central Command on June 7, 1967, spoke of:

Homes, suddenly abandoned, left intact; geranium bushes in planters, vine branches climbing balconies, the smell of the tabun smoke still lingering in the air; elderly folk with nothing left to lose, lumbering along.

A better-known description of the scene was provided by author and journalist Amos Kenan, who, as a soldier, participated in the short battle. A letter he wrote to MK Uri Avneri on June 10 stated:

The first bulldozer came in the early afternoon. It destroyed homes, with items and belongings still inside. Then, a group of refugees showed up, mistakenly thinking they could return. They had been walking for four days, elderly folk, mothers with babes, children parched for water. They said they had been cast away wherever they went.

“plagued by mixed feelings”

The kibbutz community of Nacshon was established in 1950 by members of Hakibbutz Haartzi and Hashomer Hatzair, a stone’s throw away from the Latrun monastery. It was the closest Israeli community to the main battlegrounds in the area. Dan Meir, a member of the kibbutz, spoke of the events in an interview he gave to Naama Harlev, another kibbutz member: “They [residents of the villages] didn’t flee. They were expelled.” In a testimony kept in the kibbutz archive, Meir described the refugee convoy: “We saw them leaving, in convoys… of clothes, camels, donkeys… They were told the village was going to be blown up.” Another member of the kibbutz, Zeev (Zaben) Bloch, spoke about the oppressive heat and the refugee convoy headed toward Ramallah.

People trying to carry what little they had, children crying, the old and the elderly lumbering by the side of the road… These sights reminded me, and many of the reserve soldiers of the time, of other, not-so-distant days when Jewish families were seen lumbering in the exact same way in occupied Europe. It was difficult to avoid the comparison. The sight was heartbreaking.

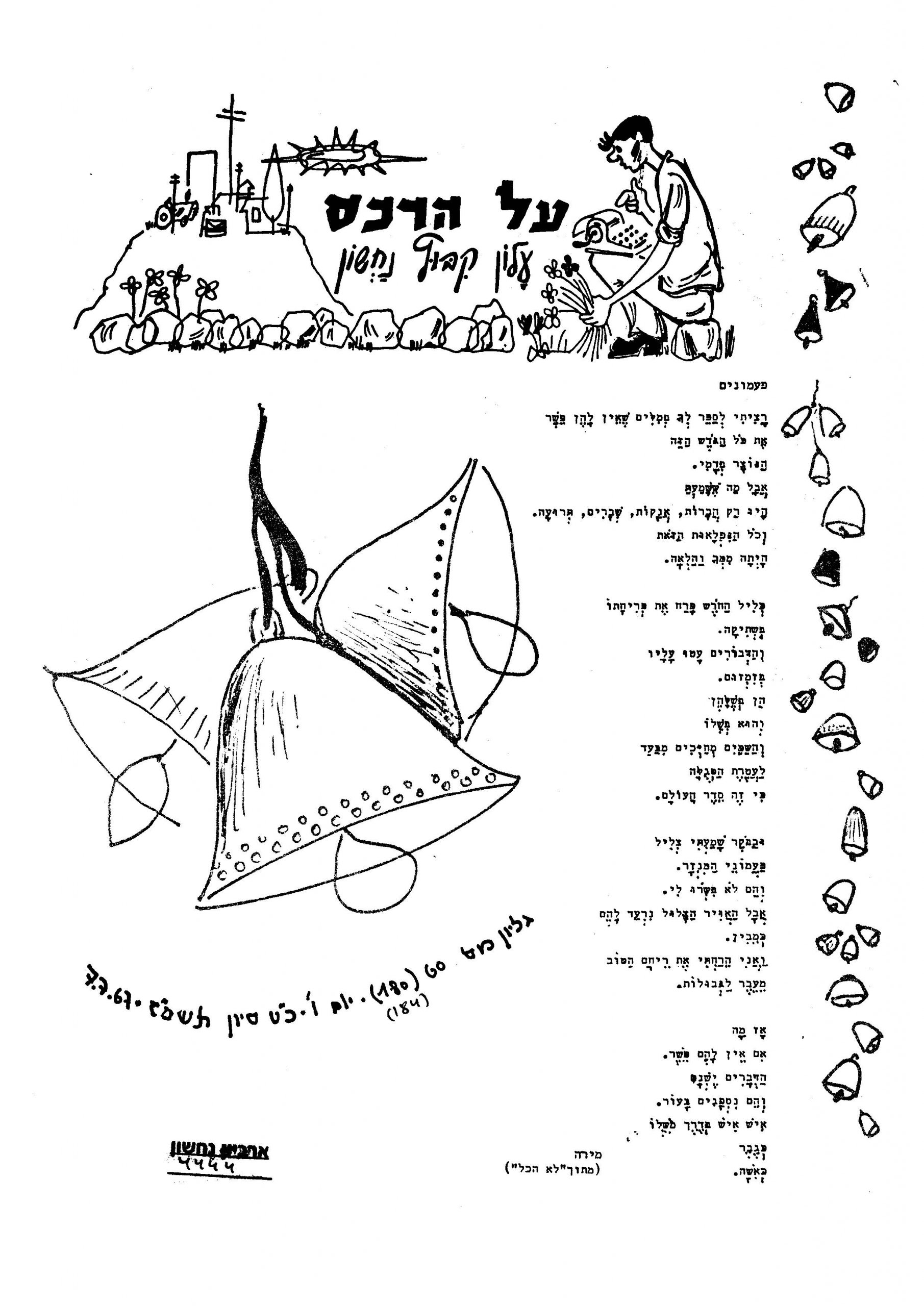

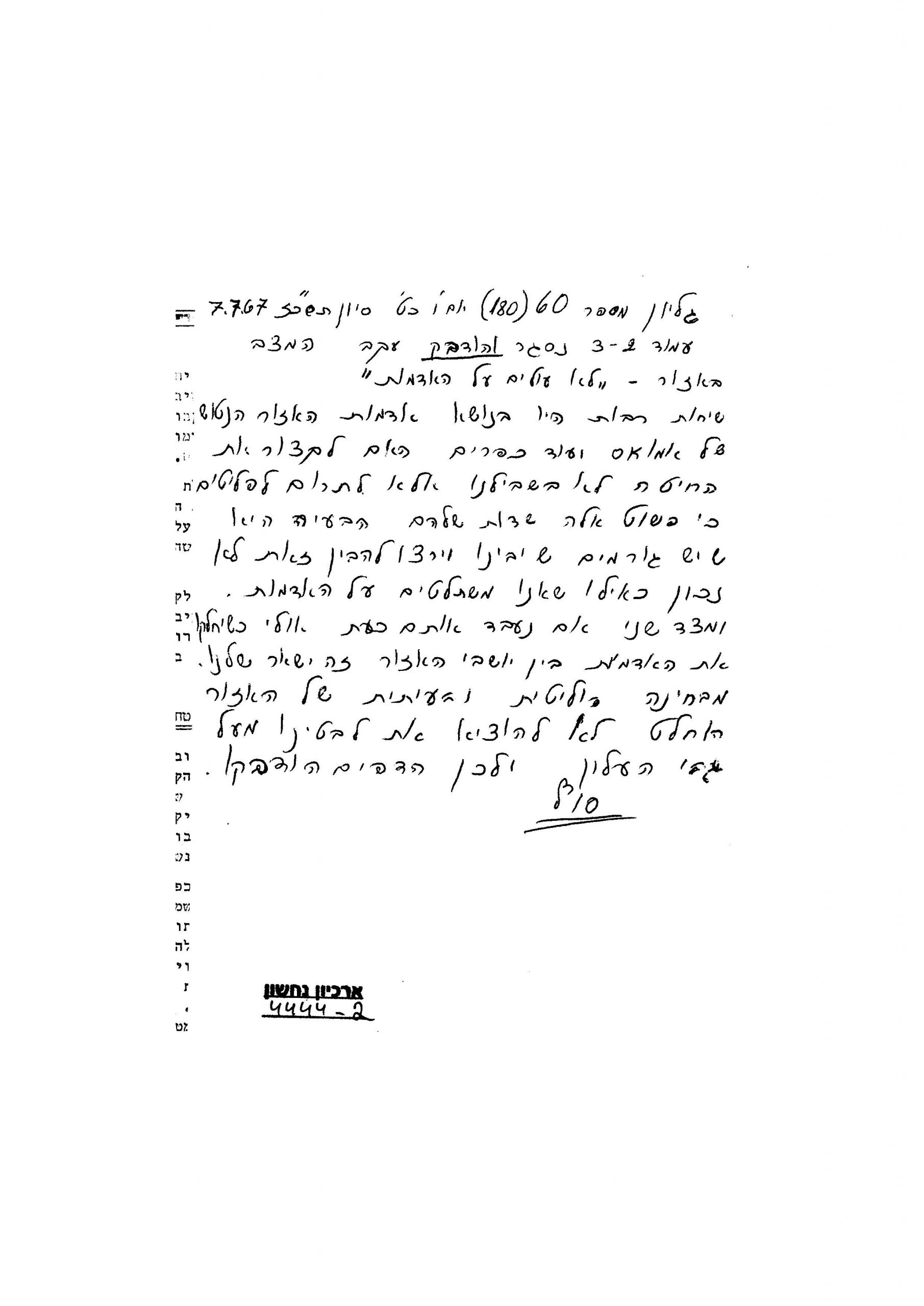

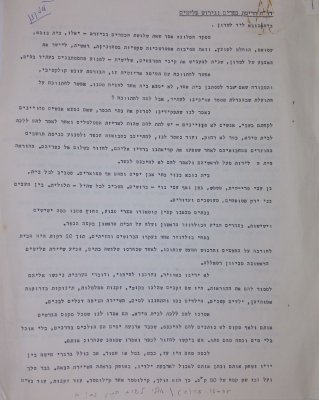

The descriptions provided by Kenan, Meir, and Bloch reverberate the discussions in the kibbutz right after the war. Two pages in the 60th issue of Al HaReches (meaning “On the Ridge”), the kibbutz newspaper from July 7, 1967, were glued together to hide what was written in them. After the issue was printed, someone had second thoughts about airing the dilemmas revealed in discussions held by the community regarding the lands of the Palestinian villages depopulated and destroyed just days earlier. Thanks to the resourcefulness of the archive’s director at the time, one copy was saved from censorship. A note attached to the surviving copy reads: “A decision was made not to air out our dilemmas in the newspaper, and therefore, the pages were glued.”

“We have been plagued by mixed feelings lately,” the newspaper’s desk wrote. “We have almost forgotten Amwas, standing in ruins beyond its walls, and its residents who have been exiled and lost their property.” Kibbutz members collectively decided not to take part in the looting of what was left behind in the depopulated villages, and even went so far as saying, “attempts will be made to locate the owners and return their belongings to them.” This was a different course of action from the one taken by other communities, whose members looted everything they could get their hands on during the 1967 war (repeating what was done in 1948). Farming tools left in the fields were collected by kibbutz members for safekeeping, to be returned to the owners when they came back, but they never did.

Nachshon members argued passionately about farming the lands belonging to the villages and the possibility of adding them to the kibbutz lands in the future – particularly the lands of nearby Amwas. The discussion mainly revolved around harvesting the grains that had been left behind and had become ready for collection. In the first discussion about the topic, the decision reached was that “the lands will not be cultivated – and we will fight for others not to take them over and cultivate them.” However, in another discussion, some questioned this decision, with one speaker candidly asking, “What will we gain by remaining honest?” The fear was that the lands would be taken over by other farming communities.

Records of the conversation between kibbutz members make for a fascinating read and are instructive of the dilemmas faced by many farming communities, first after the war in 1948, and then again in 1967. One member wondered: “By harvesting the wheat and using the land, are we not aiding in the establishment of facts regarding the dispossession of the refugees from these lands?” Another member was more decisive, exclaiming: “We have not sewn. We will not reap!” The political aspect of using kibbutz communities to dispossess Palestinian villages was not lost on Nachshon members, as one speaker clarified when he asserted this was a “’political harvest,’ meant to establish facts.”

Aside from the moral considerations, PR played a role as well. In one of the discussions, someone said, “if a photo of a combine harvester from Nachshon plowing Amwas lands is published, our denials and explanations won’t help much.” These discussions concluded with Nachshon members deciding not to farm the lands or harvest the wheat. Additionally, the kibbutz started a committee tasked with vocally protesting the destruction of the villages.

Meir, one of the strongest critics of the destruction, asserted in 1968 that it was “a political, not a security act.” His spouse, Mira Meir, a children’s author, clarified later in a testimony kept at the Nachshon archive that “all through the war, people everywhere were talking about what a moral army the IDF was, how they gave water to the Egyptian soldiers… No one spoke about the occupation, or the villages, or Latrun. It broke me… that this was where all the humanism ended, in front of my window. Because we saw, and we knew. I felt that we were humanistic and good, until it came to the villages… the expulsion.”

The residents of Amwas, Beit Nuba, and Yalo are still fighting to return to their villages and restore them.