In the early years after its establishment, Israel committed a slew of expulsions and demolitions in Palestinian villages in the country. In Khirbet Jalameh, a small hamlet in the Triangle area, for instance, all 70 residents were forcibly removed, their fields taken, and their homes destroyed – all in order to make way for the establishment of the kibbutz community of Lehavot Haviva. The Nadaf family, which owned few hundred dunams of land, fought the expulsion all the way to Israel’s Supreme Court, but even the court’s finding that “the Applicants’ removal from their lands was carried out without any legal foundation and without any justification,” did little to help the family regain possession of their property.

The expulsion and exodus of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians during the 1948 war have been discussed extensively in research and literature. However, a slew of expulsions Israel committed in the first few years after the war received less attention. Of those that did, the forcible displacement of Palestinians living in the southern city of Majdal in 1949-1950 has been particularly prominent. However, villages in the Triangle area were being destroyed at the very same time as well, and residents were expelled both there and elsewhere.

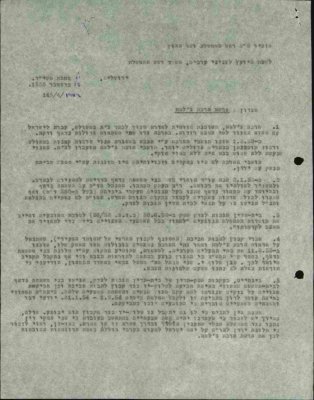

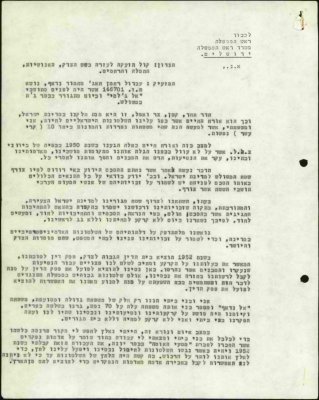

The documents presented here offer a brief overview of the forgotten story of Khirbet Jalameh, a small village that lay east of Hadera, near the village of Jat. After the Triangle was annexed to Israel as part of the 1949 Rhodes Agreements, all seventy of Khirbet Jalameh’s residents were displaced in March 1950. This was part of an Israeli initiative to move residents of small hamlets throughout the Triangle area to neighboring villages. As evinced by the Arab Affairs Advisor’s letter to the Prime Minister from December 17, 1953, the removal was carried out “without any legal expression,” in other words, without any authority.

The removal of Khirbet Jalameh was meant to pave the way for the establishment of Lehavot Haviva, a kibbutz community. In October 1949, four months before the expulsion, Raanan Weitz of the Jewish Agency Settlement Department wrote to Yosef Weitz, from the JNF, with much fanfare: “We hereby inform you of our consent to the establishment of the Lehavot Haviva kibbutz in Khirbet Jalameh.”

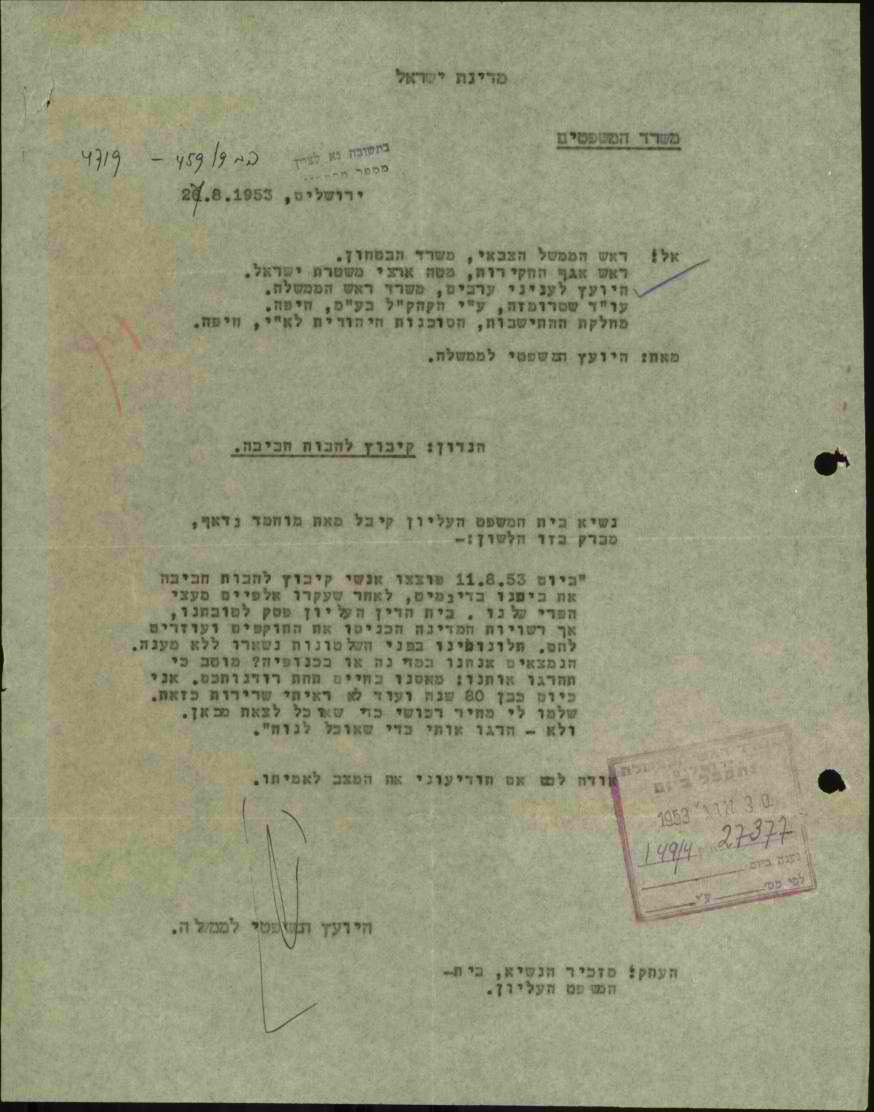

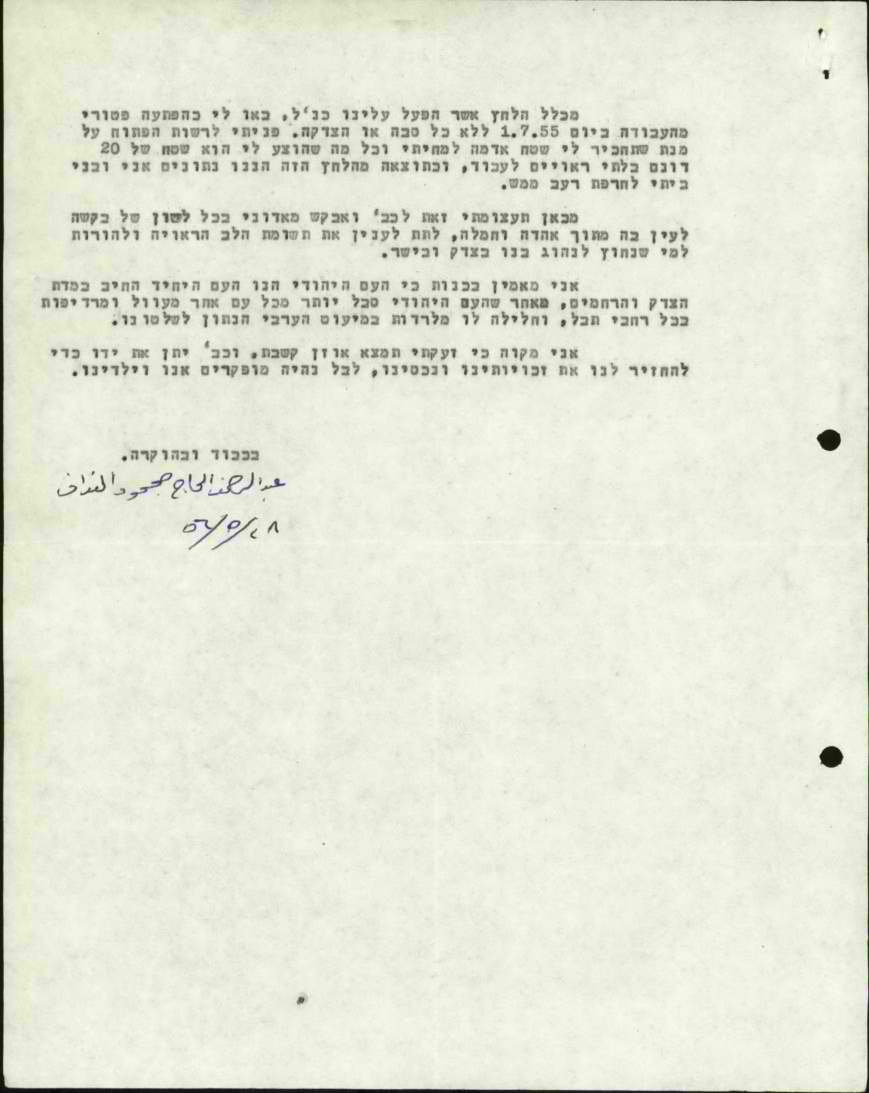

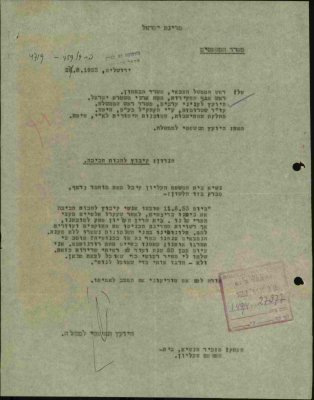

After the displacement, residents of Khirbet Jalameh were scattered among various villages in the Triangle, most of them in the neighboring village of Jat. The residents reached out to the Military Governor and the police several times, asking for permission to return to their village. After the requests went unheeded, in early 1952, one of the displaced families – the Nadaf family – who owned few hundred dunams, petitioned the Supreme Court. It was only then that the state thought of offering the residents compensation – lands belonging to absentees – Palestinians displaced by the war – elsewhere in the area. As in many other cases in which the state offered to compensate Palestinians whose lands were misappropriated with lands belonging to other Palestinians, the Nadaf family rejected the offer. In June 1952, the court ruled in favor of the family and instructed state authorities to, “utilize all measures at their disposal to put things back the way they were.” The court ruled categorically that “the Applicants’ removal from their lands was carried out without any legal foundation and without any justification.”

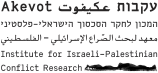

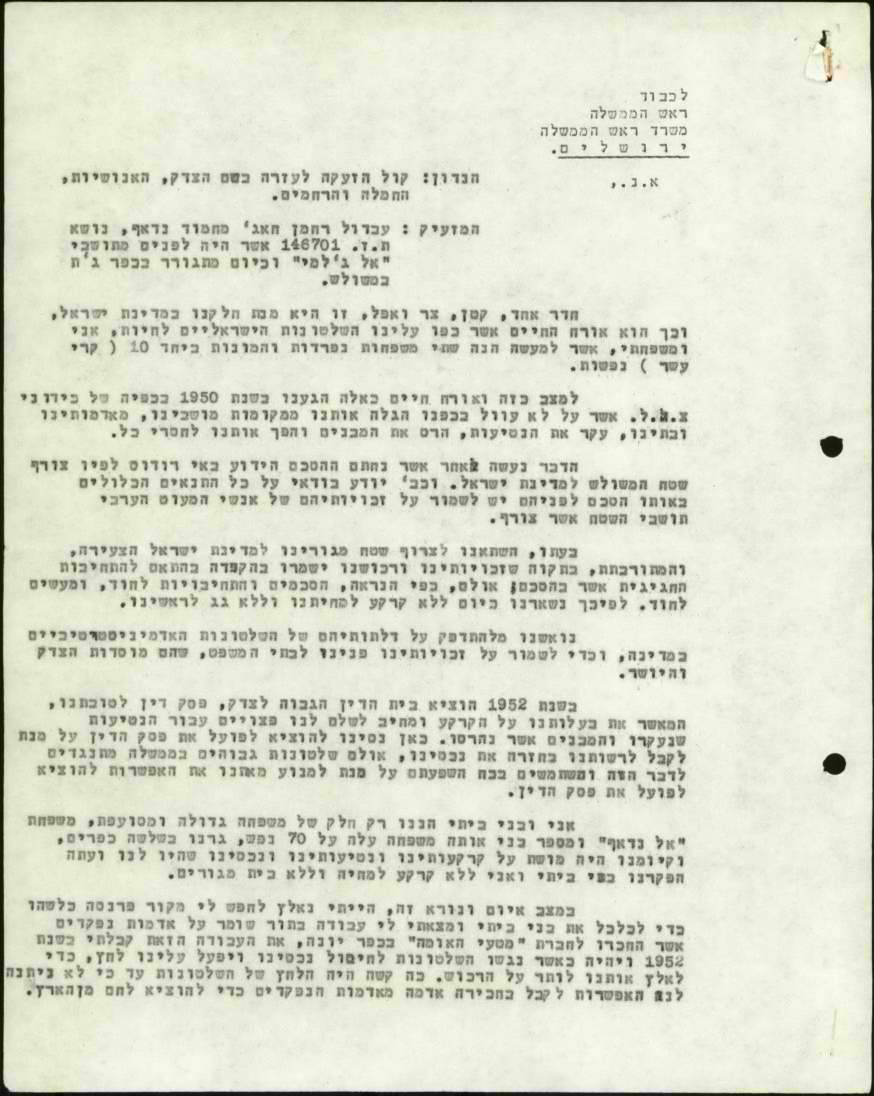

Whether the state was in any way inclined towards putting things back the way they were is highly doubtful given that a year earlier, in 1951, Lehavot Haviva was moved from its original location and was established on Khirbet Jalameh’s lands. The court judgment was never implemented, and about a year after it was delivered, in August 1953, kibbutz members blasted Khirbet Jalameh’s ancient stone structures and destroyed many of its surviving crops. Muhammad Nadaf wrote to the President of the Supreme Court: “The grievances we have brought before the authorities remain unanswered. Is this a state or a gang? You may as well kill us. We have tired of life under your tyranny. I am now approximately 80 years old, and I have never seen such arbitrariness.” The Nadaf family petitioned the Haifa District Court to issue a warrant of eviction against the kibbutz community and award compensation.

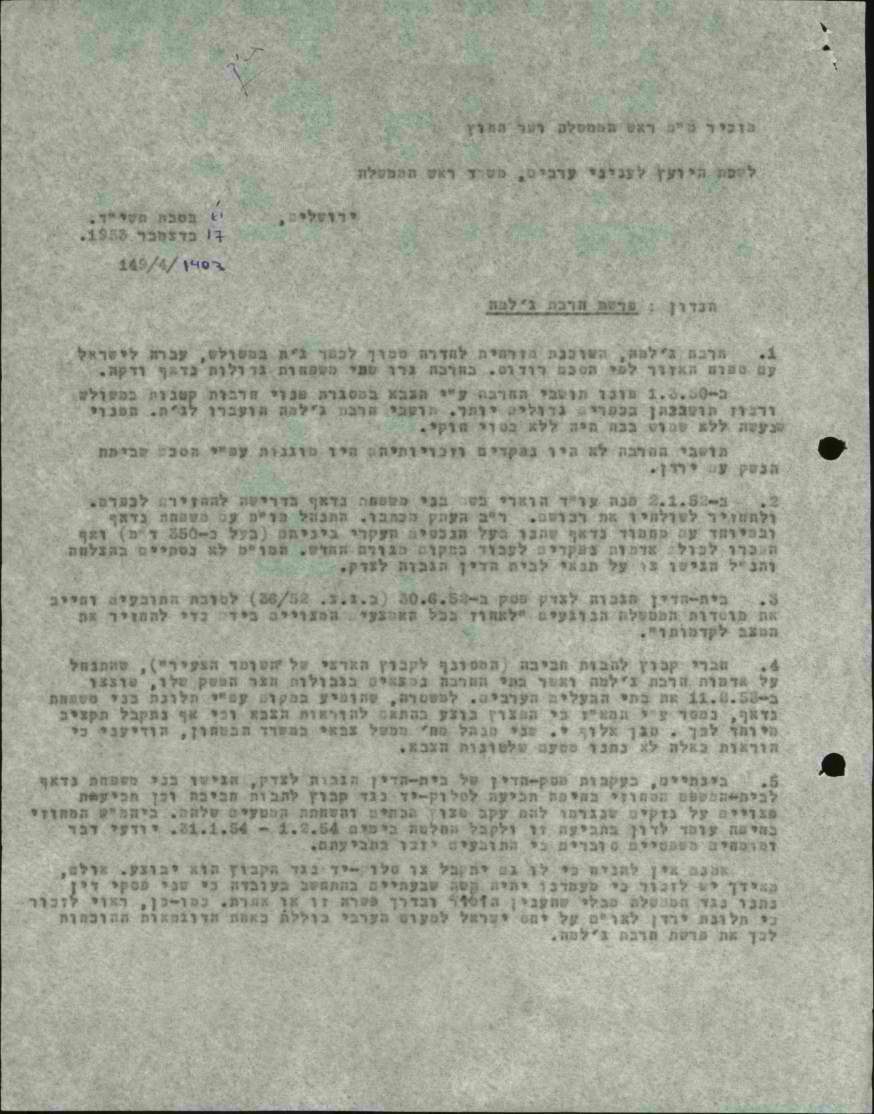

Members of the kibbutz argued in their defense that they had acted in concert with the military and with its backing (a claim also made in a book by a founding member of the kibbutz: “A Kibbutz Rises from the Holocaust: The Story of the Founders of Lehavot Haviva, Yad Ya’ari Publishing, 2009). The Military Rule, however, said it issued no such orders. Setting aside the military’s involvement in the affair, a matter that was apparently of little importance to the authorities, an assessment made by Baruch Yekutieli, the Prime Minister’s Arab Affairs Advisor, which proved true, is telling: “Even if a warrant of eviction is issued against the kibbutz, there is no reason to assume it will be executed.” In light of this, Yekutieli proposed purchasing the family’s property and helping it emigrate. This proposal never materialized, and the authorities continued to negotiate compensation with the family in the years that followed.

The enactment of the Land Acquisition Law (1953) paved the way for the continued misappropriation of Khirbet Jalameh’s lands. The Law established that any property that was deemed by the Minister of Finance not to be in the possession of its owners on April 1, 1952, and had been used for settlement or security purposes from the state’s establishment and up to April 1952, would be vested in the Development Authority and considered as having no other owner. This law undid the court’s decision.

The family’s patriarch, Mahmoud Nadaf, refused the offers he received over the years and demanded to return to his lands. In May 1956 he contacted Prime Minister David Ben Gurion and told him about the hardship his family faced following the expulsion. Nadaf passed away in 1959. Khirbet Jalameh’s relics can still be seen in the lands of Lehavot Haviva.