Shortly after Israeli forces took control of Arab cities in 1948, their residents were concentrated in separate neighborhoods, usually fenced in with barbed wire. For some Israeli officials, this conjured up “associations of horrors.”

The occupation of Arab and mixed cities in the 1948 War raised questions about the fate of the few Arab residents who remained in them. In Haifa, for instance, of the 70,000 Arab residents who lived in the city before the war, no more than 3,500 remained. In Jaffa, which had a similar Arab population, only about 4,000 remained. By the end of the war, 160,000 Arabs were living in Israel under military rule, which included a permanent curfew and a strict travel permit regime.

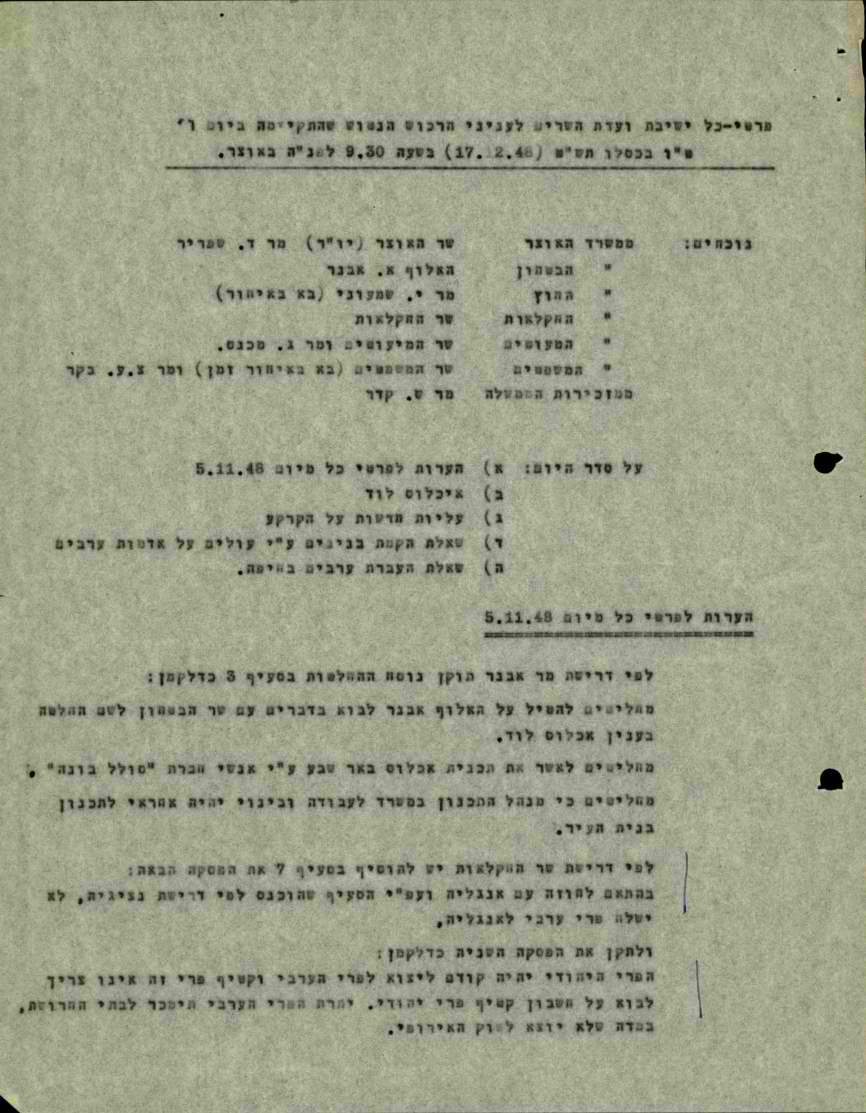

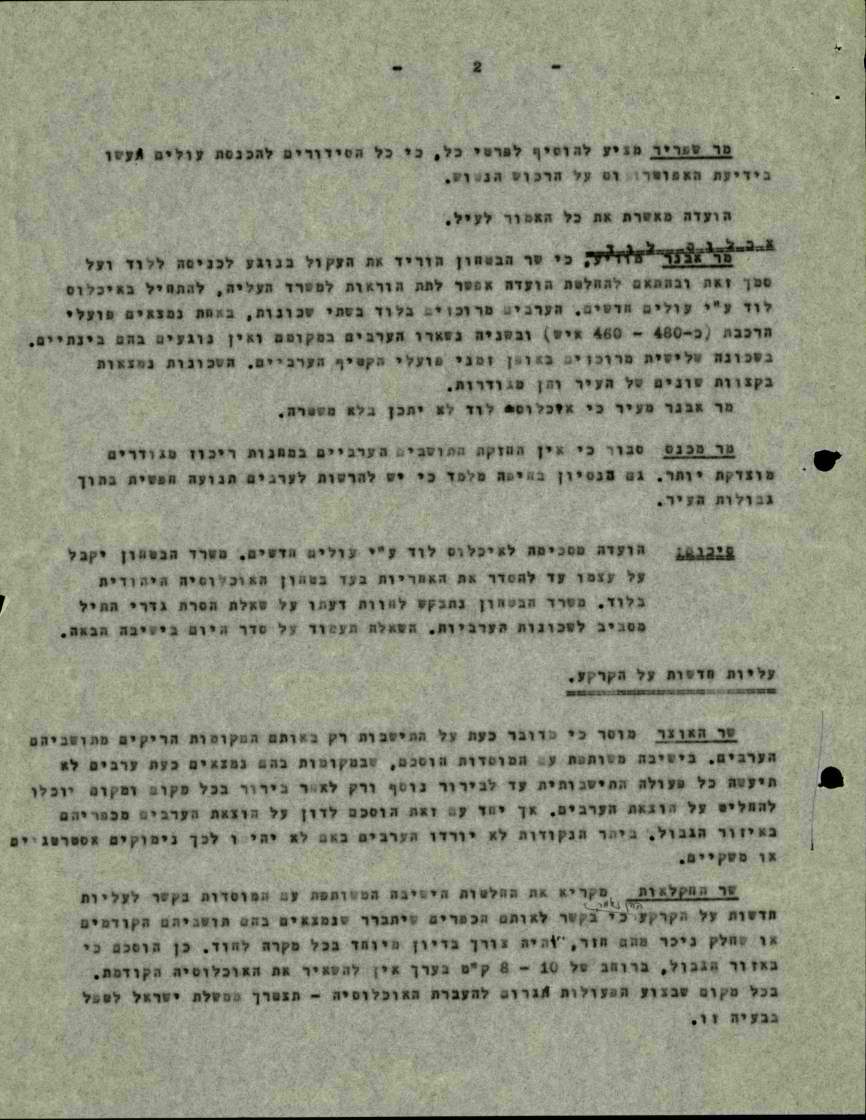

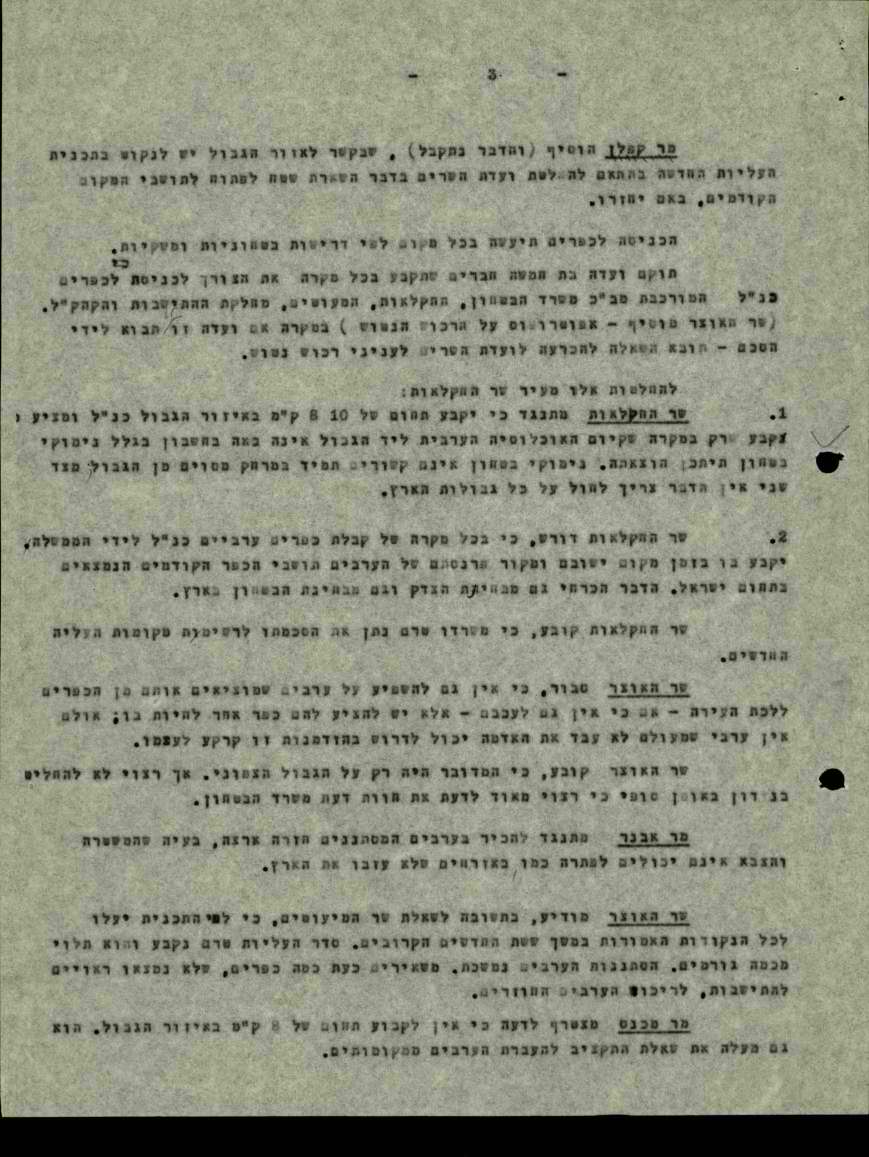

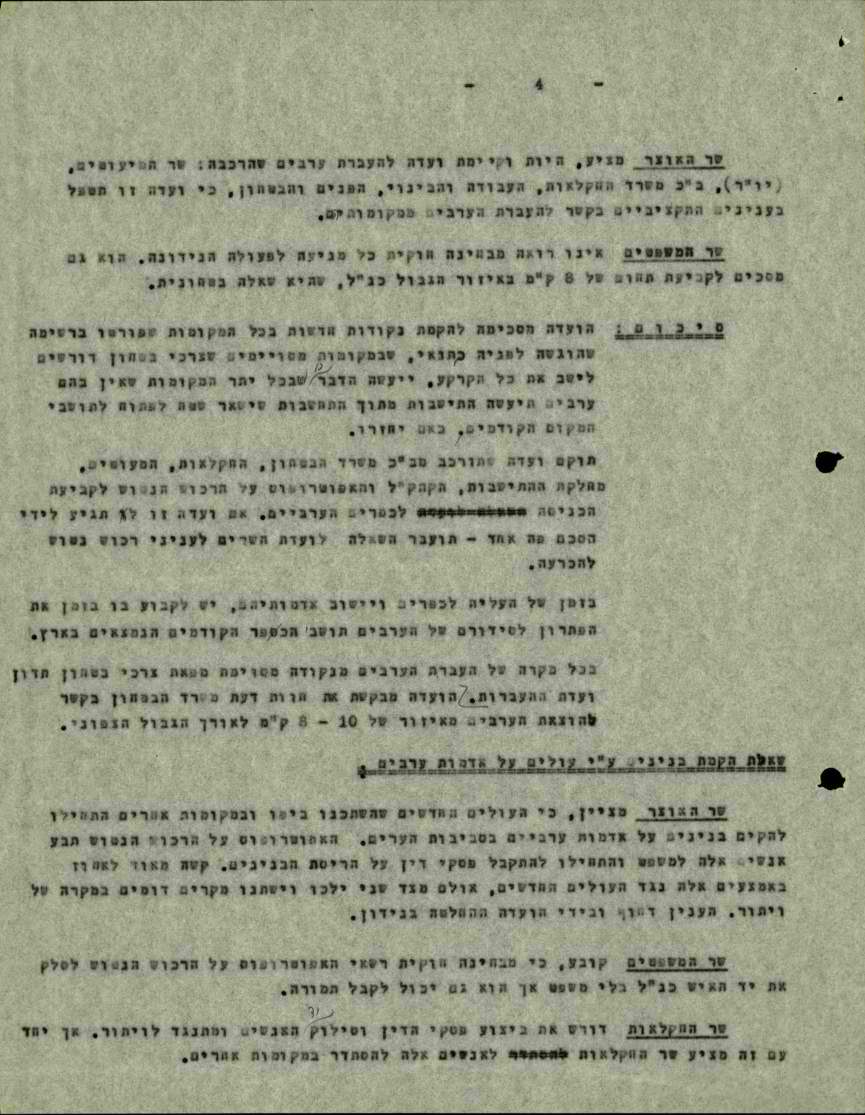

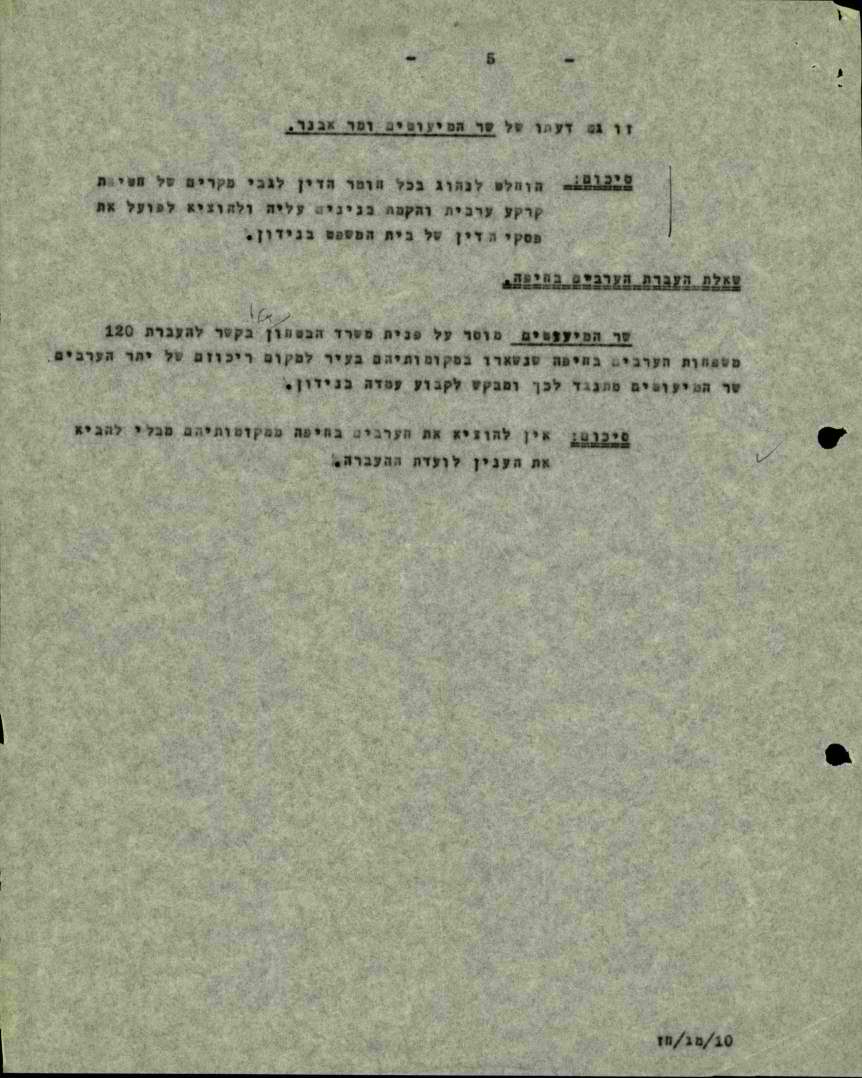

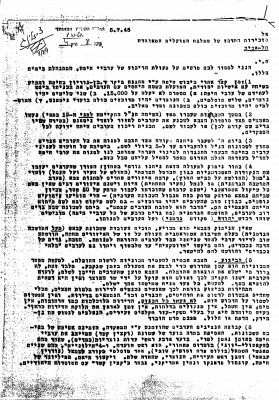

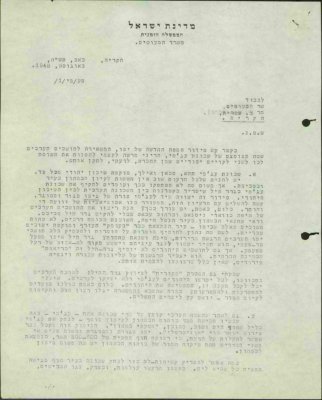

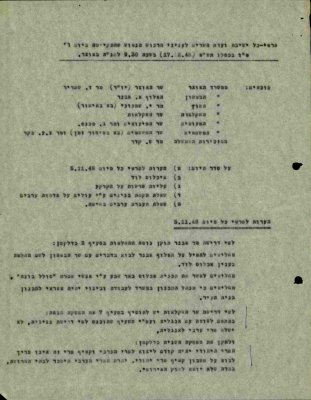

A large number of historical records from this period are still closed for public access, despite the many years that have gone by. Other records, which have been opened for public access but remained partially censored, may hint at the rationale for denying access. Transcripts of a Ministerial Committee for Abandoned Property meeting from December 1948 provides a glimpse into the issues the Israeli establishment was considering at the time. In this meeting, the committee discussed concentrating the Arab residents of the city of Lod in designated neighborhoods to make way for moving Jewish immigrants in. Director of the Ministry for Minority Affairs Gad Machnes said in the meeting he believed, “keeping the Arab residents in fenced concentration camps was no longer justified.” The Israel State Archive has recently censored this sentence, blacking it out in the document. The logic is clear: Arab citizens have no right to know their past, and anything Israelis do not like to hear gets censored.

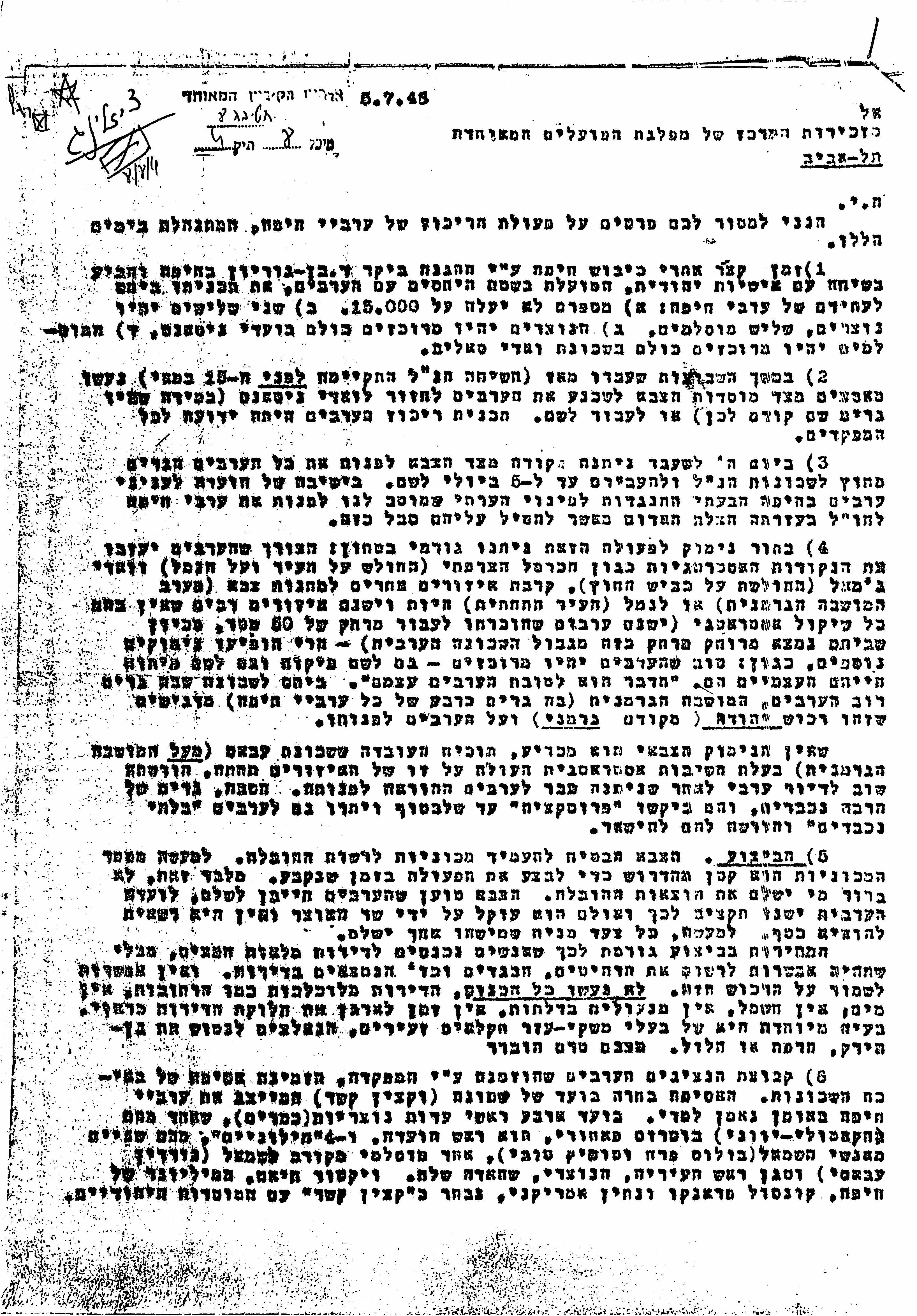

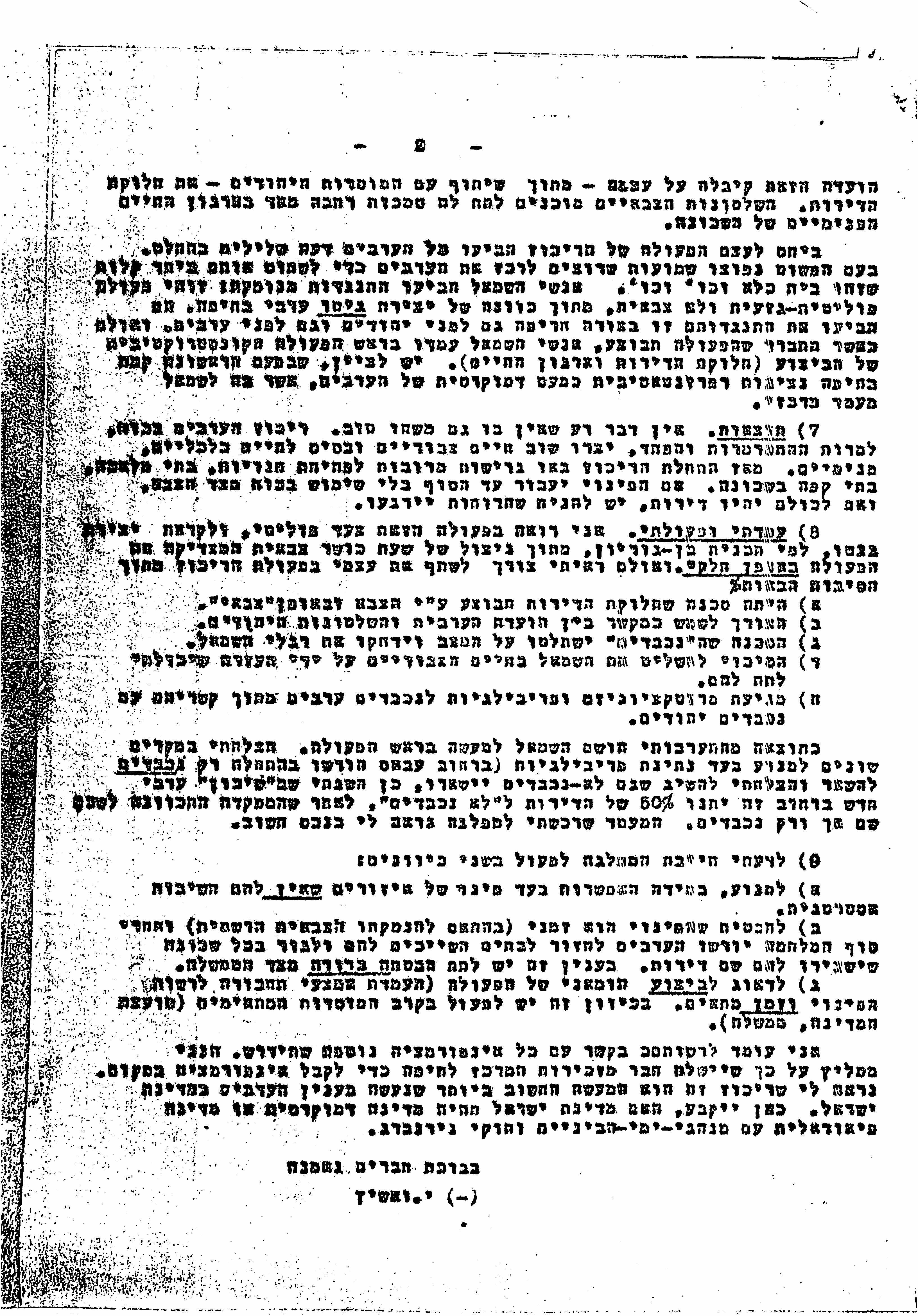

The pattern was repeated everywhere Arab residents were relocated. For instance, in Haifa, Prime Minister David Ben Gurion ordered to concentrate Arab residents in the Wadi Nisnas area. Yosef Waschitz of the Arab Department in the United Workers’ Party (Mapam), who was at the center of the events in Haifa during those days, reported about the chaos that followed the decision: It was impossible to keep property safe; the apartments were filthy, and they had no water or electricity. Waschitz opposed the concentration of Arab residents and considered it a test for Israel’s budding democracy.

In Jaffa, Arabs were to be relocated as well. “It is better to have special areas for Jews and areas for Arabs,” Military Governor Meir Laniado told members of the Arab Committee in the city in July 1948. Moshe Erem, who directed the Rehabilitation and Promotion of Relations with Minorities Department at the Ministry for Minority Affairs opposed the concentration of Arabs in the Ajami neighborhood, which was surrounded by Jewish neighborhoods, and informed the minister in charge of his position. Erem noted there were no concerns for the safety of the city and its environs and that fencing in the Arab area with barbed wire “will immediately give Ajami the form of a sealed ghetto,” adding, “It is difficult to accept this notion, which amply evokes associations of horrors for us.” Like Waschitz, Erem also thought that creating a ghetto would have a negative impact on future relations with Arab residents: “And once more, by this, we plant a poisonous seed (…) in the hearts of the Arab residents”, he said. “A barbed wired ghetto, a ghetto without access to the sea.”Ajami was ultimately fenced in for months. City resident Isma’il Abu Shehadeh recounted: “They put barbed wire fences around us with three gates in them. We could leave the area only to work in one of the citrus groves around the city, and for this, we needed approval from the employer”.

In Lod too, Arab residents were concentrated and put under lockdown. In January 1949, the Ministry for Minority Affairs and the minister in charge, Bechor Shalom Sheetrit, demanded the military administration take down the barbed wire fence around the Arab part of the city. It was not until July of that year, when the military administration in the city was canceled, that local residents were allowed to move freely. The barbed wire fence, however, remained.

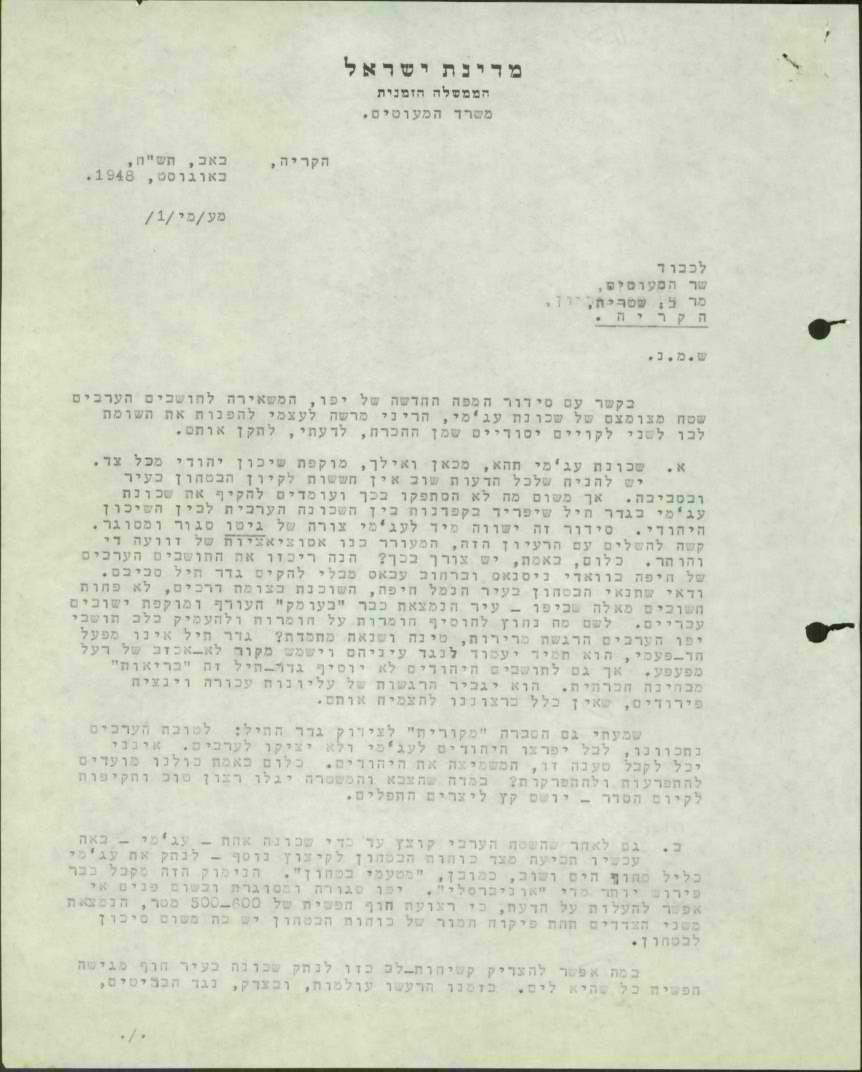

Archival records depict the closure of neighborhoods with Arab residents in other cities as well, such as Majdal and Acre. Minister Sheetrit expressly objected to “setting up ghettos for minorities,” as he phrased it. In a letter he sent to the government ministers in mid-1948, Sheetrit wrote that the relationship between Israel and its Arab residents is “flawed and broken” and demanded “laying down a clear line of equal civil rights,” lest reality takes its vengeance on us.

An article by Akevot Institute researcher Adam Raz about the closure of neighborhoods with Arab residents after the 1948 war was published in Haaretz daily newspaper.