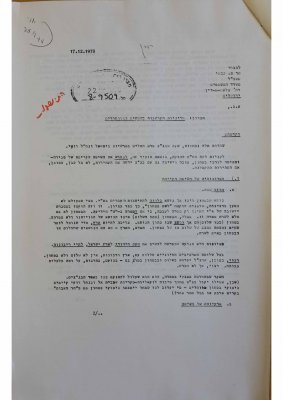

Condemnation for the practice of using fictitious security reasons as a guise for building settlements usually come from the opposition to the settlement enterprise. It is rare to see this false excuse exposed by those who support it, or, in this case, from one of its leaders. This rare opportunity comes in a letter sent in December of 1978 by lawyer and columnist Elyakim Haetzni to the director general of the Ministry of Justice at the time, Meir Gabai. The letter offers an unusual glimpse into the system used to dispossess Palestinian landowners, oddly by someone who has no compunction about the issue.

The background for this letter was a high court petition that was pending before the court at the time regarding a new settlement in Beit El, north of Ramallah. It was filed by Palestinians who were barred access to their lands, which had been seized by Israel to build a new settlement. The lands were originally seized using the usual security pretense, back in 1970, to build a military base and firing zones around it. Later on, when the civilian settlement was built, the landowners petitioned the Supreme Court, arguing it was illegal to build a civilian settlement on the land that had been seized for security reasons.

Even before the court delivered its decision (ultimately rejecting the petition and consequently approving the settlement), it was Haetzni who wrote to the director general of the Ministry of Justice to protest the impropriety of using security reasons to cover up the dispossession of Palestinians. Except, Haetzni’s criticism did not focus on the dispossession. He was less bothered by that (seeing the main difficulty in having to compensate Palestinian landowners). What upset him was the justification used to dispossess the Palestinians of their lands and the fear that the system would not last long. In his letter, Haetzni protested the use of security reasons for the purpose of settlement in the OPT. The flaw in the system, Haetzni candidly wrote, was the “lie” it was built on, adding, “Just as it was never seriously argued that Degania was ‘built for security purposes’, the same holds true for Kfar Etzion.”

On a more practical note, Haetzni stated that using the security fiction was not stable enough and could “backfire in one of the high court petitions.” Haetzni wondered, “Who is to say that security reasons will be found for Patriarch Mount or Kiryat Arba or any other site?” Another disadvantage Haetzni identified in continued reliance on security seizures might also be surprising. The system, according to Haetzni, was harsh and cruel toward Palestinian landowners as it kept them in limbo about the future of their land. The prolonged and multi-faceted harm to Palestinian landowners was exposed as Haetzni described how the two-phased system worked: It begins with a “temporary” closure of the area, which gradually becomes permanent as years go by, followed by the permanent seizure of the lands. The letter omits the next phase – building settlements on lands taken for “security purposes”.

As a lawyer, Haetzni was well aware of the fact that Israel’s policy defied international law. On this issue, he wrote to Gabai that the policy of seizing land for security reasons was “chosen partly (perhaps mainly) in order to ‘come out on the right side’ of these conventions”, as he refers to the Hague Convention and the Geneva Convention. He expressed concern that this was a “trap” that would eventually backfire and stand in Israel’s way to effecting sovereignty over the territories it occupied, citing this as another reason to stop relying on security purposes.

Haetzni did not stop at analyzing the faults in the existing system, but proposed an alternative legal solution for landgrab policies in the West Bank. Haetzni wrote, “The proposed solution is to be open and honest and expropriate land for public needs as the matter is handled everywhere else in the world. For Haetzni, the advantage of this proposal was clear: “Should such an expropriation end up before the High Court of Justice, it would no longer be necessary to come up with weak security excuses.”

Several months later, in June 1979, another petition was brought before the High Court of Justice – this one relating to seizure of lands belonging to residents of the village of Rujeib, near Nablus. The lands were again seized for “security” reasons, and again in order to build an Israeli settlement: Elon Moreh. Surprisingly, settlers openly expressed a position similar to Haetzni’s in this case, and in an affidavit they filed with the court, had no reservations about exposing, once more, the obvious lie: “The settlement itself […] does not stem from security reasons and physical needs, but rather from the force of destiny and the return of Israel to its land.” The settlers’ affidavit and Haetzni’s letter, which offered ways to reinforce the legal and practical platform for continued settlement in the West Bank, provide an illuminating, honest and stark perspective on the settlement enterprise: a political endeavor devoid of any security logic – the complete opposite of what the state has been arguing for years.