Over the years, various songs and comedy sketches have been banned from Israeli radio and television. An attempt during the first intifada to ban two songs by two different singers, Nurit Galron and Chava Alberstein – kicked up a bit of a storm that tested the boundaries of state interference in free speech.

In April 1989, the IDF radio station, a popular mainstream radio station in Israel, decided to stop playing a new song by local singer Nurit Galron, entitled “After us, the deluge” (music by Arkadi Duchin). It was during the first intifada, and the song railed against Israeli apathy to the events in the Occupied Territories. Galron sang: “There’s a country of rocks and firebombs / and there’s Tel Aviv burning with night clubs and lust […] No, don’t tell me about a girl who’s lost her eye / It just brings me down, down down down, it just brings me down.”

Almost as soon as the song was released, after a handful of radio plays, the military radio station decided to limit its rotation. Nachman Shai, who was the station’s commander at the time and today serves as Minister of Diaspora Affairs on behalf of the Labor Party, explained: “the song has not been blacklisted, [the decision was to] limit rotation and have it approved by [Dalit] Ofer [the music division manager] and myself. The reason is the text, the way the Palestinian matter is portrayed in it. There’s a glorification of the issue there, lines that are difficult to accept. We’ll play it on special occasions, for example, if we do a show about Galron or Duchin. I don’t want it played carelessly.” (Hadashot newspaper, April 5, 1989). Another song by another Israeli singer received much the same treatment in those days – Chad Gadya – by Chava Alberstein. Alberstein wrote: “How long will the cycle of horror last? / Hunter is hunted, beater is beaten / When will this madness end?”

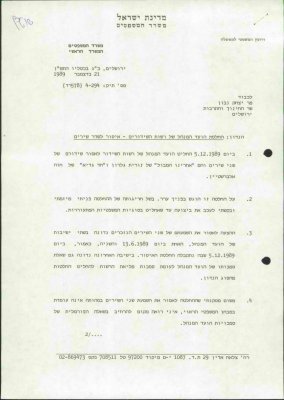

In the months that followed, the public broadcaster, the Israel Broadcasting Authority (IBA), also discussed these two songs. Over the course of two board meetings (On June 13, 1989, and December 5, 1989), it decided to ban both. The board, composed of representatives of political parties, was split, representatives of the right-wing Likud party (Shlomo Kor, Uri Oren and Amnon Oren) and the Mafdal (the religious-nationalist party) representative (Uri Falah) voted to blacklist the songs, with the latter referring to them as “PLO songs.” Dalia Itzik, the representative for the Alliance (Labor) party and Chair of the Board Aharon Harel, voted against, and after losing, submitted an appeal to Minister of Education and Culture Yitzhak Navon, whose office was in charge of the IBA. Notably, the IBA’s legal advisor, Matan Cohen, found the decision was illegal and that only the IBA’s plenum had the power to ban songs (Hadashot newspaper, December 6, 1989).

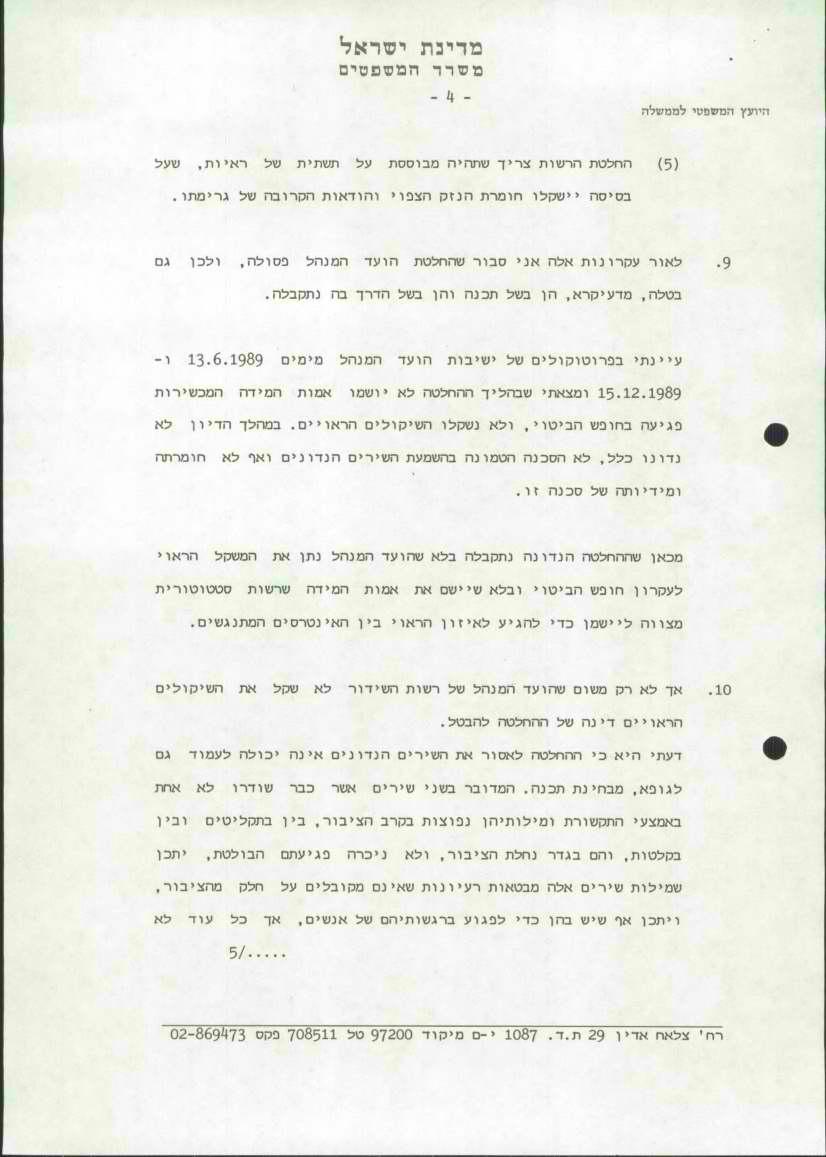

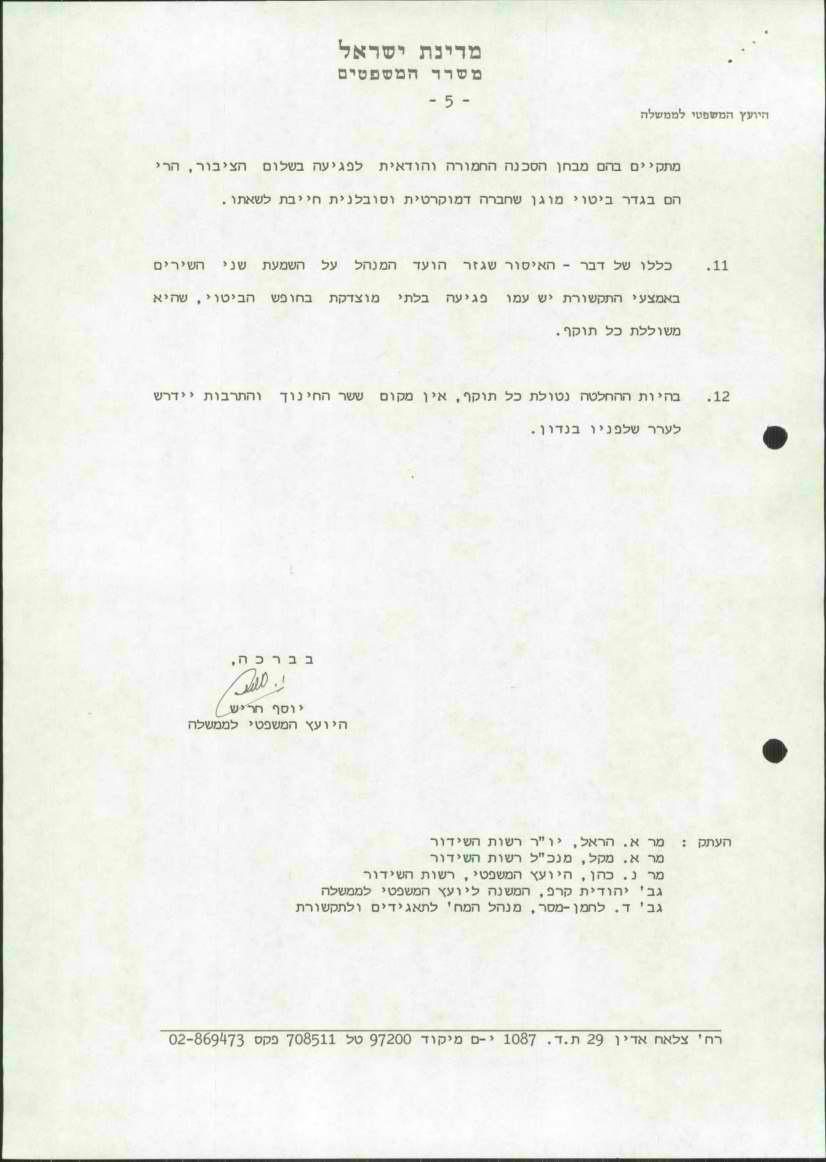

The appeal submitted to Minister of Education Navon prompted Attorney General Yosef Harish to provide the Minister with his position on the board’s decision. The AG’s memo, posted here, notes: “The matter herein concerns free speech and the competency of a governmental authority to prohibit broadcasting something that amounts to expression or speech due to its content and the idea it encapsulates.” Harish found that the decision to ban the songs “failed to pass legal muster,” adding “free speech is not just freedom to express widely accepted notions, but also the freedom to express dangerous, irritating and divergent opinions loathed by the public.” As for the song’s subject matter – the events in the Occupied Territories, Harish said: “These songs’ lyrics might convey ideas that are not acceptable to some members of the public, and may even offend some people’s sensibilities, but so long as they do not reach the threshold of clear and present danger to public safety, they are protected speech that a democratic, tolerant society must bear.”

Shortly after the AG’s intervention, the IBA retracted its decision, and the two songs were cleared for broadcasting.